Robert Braden is a retired Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Army. He was a platoon leader in the 78th Infantry Division in the 1940s. 2LT Braden was a part of the taking of the Ludendorf Bridge, which was a major turning point in WWII. After Crossing the Rhine River, he and the rest of the 78th moved to the interior of Germany to help end the war.

Robert Braden was born in 1922 in Byron, MI. He grew up on a small family farm owned by his father. He attended Byron High School and graduated in 1940. He attended college at Michigan State University where he earned his bachelor’s degree in Agricultural Education. He also participated in the Army Reserve Officer Training Corps while attending school.

After graduation, Braden commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army. He was sent to training events for nearly a year to become an infantry lieutenant. This was a frightening job. According to Braden, only about 10% of infantry lieutenants made it through an entire combat tour without being killed, captured, or injured. During his training a superior was looking for volunteers to be anti-tank officers. Braden was selected to do this and was very thankful. When his training finished he became a platoon leader, taking command of an Anti-Tank platoon in the 310th Regiment of the 78th Infantry Division in 1944. The 78th Infantry, known as “Lightning” and comprised of the 309th and 311th infantry regiments, and 310th anti-tank regiment, spent some time training in the U.S. before leaving for Europe.

On 14 Oct. 1944 the 78th Infantry set sail for England from New York City. Braden recalls the trip, saying “it felt nearly endless”. His ship was a part of a convoy being escorted by U.S. Destroyers in order to protect the troops and supplies being shipped over seas. Braden said that he didn’t believe there was anyone on the ship that didn’t get sick at some point from the ocean waves. After nearly two weeks on board the massive ship, they arrived on 26 Oct. Braden, along with the rest of the division, trained for a month with his platoon to ensure they were prepared for the job that awaited them on the continent. After successfully preparing themselves for war, the 78th crossed the channel into France and made their way to Belgium near the front line to prepare for combat. While most of the 78th was loaded into train cars and shipped across the continent to Belgium, the 310th was able to move by convoy. They were granted this privileged because the 4 platoons in the 310th each had 3 anti-tank guns attached to trucks which could hold the squads in charge of the guns. The men and guns of the 310th took roads to Belgium and met up with the rest of the 78th there.

Braden’s division was deployed to the Hurtgen Forest on 10 Dec. 1944. The 78th Division was activated and moved in to replace the 1st Infantry Division throughout the front line. Among the new regiments charging into central Europe was Braden’s platoon of anti-tank soldiers. This would be the first time most of them had seen real war.

Moving Forward

After leaving Belgium, and 7 months after the invasions on D-Day, the front line was only starting to advance into the western outskirts of Germany. There was fighting and resistance by Axis forces, but not as much as the Allies would encounter as they progressed deeper into the country. Early in their deployment, Braden’s division was responsible for taking the Shwammenauel Dam. The capturing of this dam was important because it provided the allies a path into central Germany. The Germans controlled the dam and had the ability to destroy it. This would have flooded the land for miles downstream making it impossible to cross the river until the area drained.

The Battle of the Bulge

The 78th lead Allied forces into the heart of Germany where they met an intense counteroffensive from the Axis. “This was a surprise move” said Braden, whose company was in charge of setting up security in all directions to prevent his men from being surrounded. Fighting continued for 6 weeks as the Allies tried to push back the intense waves of German soldiers. Most of this fighting took place in the dense forests of Ardennes in the cold of winter.

Braden recalls the Bulge, as well as most of the march across Germany. He said most of their time fighting consisted of holding their position until a squad could move forward and destroy the machine gun nests known as “pillboxes” that prevented the Allies from moving. This was a dangerous job. Pillboxes were small concrete bunkers with ports large enough to fire a machine gun out of. Often times, the only way in was through a tunnel that ran back into enemy territory to far to reach. The allies would send a squad to flank the pillbox with a large charge. One man would climb on top of the nest, set the charge, and leave with the rest of his squad. Detonation would destroy the pillbox and usually kill anyone inside. After destroying one, the line would move forward until they were pinned down again by a new pillbox. This was most of the deployment for Braden and the 78th

Braden’s men had an extremely important job. The Germans were launching this offensive across the entire western front. Any break in the line would have allowed German companies to move behind the Allies and attack them from two sides. Had the 78th failed, the war may have ended very differently.

Eventually the Germans were pushed back. The Battle of the Bulge was an extremely time consuming and deadly engagement that nearly spelled the end for Allied forces. However, due to the resilience and determination of people like Braden and groups like the 78th Infantry all along the western front, the Allies were able to move forward again. The 78th made their way east toward the Rhine River. They found themselves in the city of Remagen where one of the few remaining bridges stood. The Axis powers had destroyed most of the crossings making it very difficult to advance into the heart of Germany. The Ludendorf Bridge was one of the last standing bridges over the Rhine River.

The Battle for the Ludendorf Bridge

When they reached Remagen, Braden’s platoon was sent a few miles south on the river to set up security. It was there job to make sure the Germans didn’t flank from the south while the rest of the 78th fought for control of the Bridge. Braden’s troops set up there position and expected it to be a quiet night. They were surprised at how quickly the bridge was taken and they were called up to cross the river. The rest of the 78th had spent hours fighting the Germans for control of the bridge. According to the soldiers, there were explosives in place to demolish the crossing. “The Germans could have blown up the bridge.” said Braden in an interview with the Argus Press of Byron, MI. They were apprehensive about crossing, but knew that it was necessary.

The bridge was originally a railroad crossing that had boards across the tracks to allow men and vehicles to move over it. It was dark and Braden recalls that there were a few men who fell through holes in the planking to the river below. For a time the road had been blocked by a tank parked sideways across the bridge. After a while, the way was cleared and the bridge was open again. Thousands of troops were in line to cross when Braden’s platoon arrived. Luckily, they were called up early to cross because they had anti-tank guns that were needed on the other side of the Rhine.

Taking this bridge was a major turning point in the war. Allied forces poured across the Rhine, which was the last major defensive line keeping them out of central Germany. After a month, the Ludendorf Bridge collapsed due to damages sustained before and during the battle. However, more than 25,000 allied troops had crossed and several temporary bridges had been constructed nearby. This opened up central Germany for troops to march in and end the war.

Ending the War

The 78th , along with other allied forces, moved towards Berlin in an effort to end the war. They continued fighting what was left of the German military, though most of their defensive positions had been captured, destroyed, or exhausted. With their forces severely depleted, the Germans could not put up much of a fight. The Americans and British were pushing forward from the West while the Soviets where marching in from the East. Braden had said that after taking the crossing at Remagen, they knew the war was over. Allied forces, including the 101st Airborn Infantry division, were making their final march to the capital to destroy the German leadership. Braden’s platoon along with the rest of the 310th moved south to clear the agricultural areas below the industrial section of Germany. Braden recalls that there was no fighting. Germans would pile their weapons in the middle of their towns and wait for the Americans to come and accept their surrender. The majority of their work was transporting thousands of prisoners back behind the front line every day while they moved toward Berlin. The war in Europe was over.

On 17 April 1995, The 78th Infantry Division was pulled off the lines. They were being replaced with fresh troops to finish off the enemy. It was bitter sweet to push so far into the heartland of the Axis and not finish the job themselves, but the men were glad to finally get a rest. Berlin fell to the Allies on 8 May 1945, ending the conflict in the European Theatre. Braden and his men had fallen back behind the lines until the end of the war. After the fall of Berlin, they moved into the city to be part of the occupation

While in Berlin, Braden was placed in charge of entertainment for the occupying forces. He was selected to stay because he was unmarried with no children. For the next 11 months he set up beer gardens, sports leagues, and other practices to keep up morale until the troops withdrew back to the States. It was a relief to be doing something other than fighting for the first time in months. Braden recalled that the German people took very kindly to the American soldiers. This was due, in his opinion, to their fear of the Soviet occupying forces. Braden says that the Russians were notoriously violent and oppressive to the civilians in Berlin. He was glad to be seen as part of the merciful force.

Over the next month, German military leaders and political officials were arrested or committed suicide periodically. The last German held areas around the world surrendered and the soldiers were taken prisoner. Americans as well as other Allied forces remained in Berlin in limbo until early June when the Allied Control Council officially assumed power over the country. The majority of soldiers were shipped back to the States to include Braden and the 30 men of his anti-tank platoon.

Life After the War

After the war Braden got married and took a teaching job at Byron High School. He revived the Agricultural Education Department in the high school. He also built up the Byron Chapter of the Michigan FFA, which remains largely successful to this day. He continued teaching for 10 years in which time he fostered one of the most successful agricultural programs in the state. After retiring from teaching he spent another eight on the school board. He is still an active supporter of the school, FFA, and sports teams.

Immediately after the war, he bought his family’s 139 acre farm and continues to live there today. He raised asparagus for most of his life until he decided it was time to retire and rent the land to his niece and her husband to farm. Having owned the farm since the end of the war and being in the family that established it, Braden Farms was named a Centennial Farm 2 years ago and is now a state landmark. Since returning to the farm he has had 3 children, 5 grandchildren, and 11 great grandchildren, all of whom attended or currently attend school in Byron.

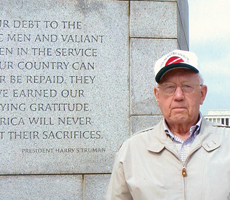

More than 70 years late he says that he still remembers the names of all the men in his platoon. He was not comfortable discussing the war for a long time. He told the Argus Press “Only after you hit 90 will you talk about it. Before 90 you don’t talk about it. He says that he is proud to have been a part of what came to be known as “the good war”. Braden was part of the 2014 Honor Flight. This is a program set up every year to fly World War II veterans to Washington D.C. to visit the WWII memorial. This is designed to show honor and provide closure for veterans, which is exactly what it did for Braden.

Before coming to Michigan Tech I had the privilege of working for Mr. Braden. He is very active for his age (now 93 years old). He hires boys he knows from town to maintain his house and farm since he is no longer capable. He has pictures on the walls of him in England and Germany as well as pictures with his platoon. It wasn’t until after leaving town that I was aware of the role he played in the war and the importance of what his platoon did with the 78th infantry to defeat the Axis forces. It is truly an honor to know and have worked for a man who has lead such an awe inspiring life.

The information in this Article comes from multiple online sources outlining movements of Allied troops during WWII, an article printed in Braden’s hometown about his account of the war, an interview conducted on 28 Nov. 2015 with Braden in his home, and two books outlining the war for the 78th as a whole and for the 310th specifically. These books were given to Braden after the war.

Primary Sources:

- Parker, E. (2003, January 3). Lone Sentry: Lightning, The Story of the 78th Infantry Division — WWII Unit History (G.I. Stories, Stars & Stripes, Paris 1945). Retrieved October 12, 2015, from

- War Department Bureau Of Public Relations film # BPR-1125,The Rhine Crossing, 1945.

- DA Poster 21-32: The Remagen Bridgehead – 7 March 1945.

- Interview with Robert Braden. Conducted 28-Nov-2015

- The Story of the 310th Infantry Regimen, 78th Infantry Division in the War Against Germany, 1942-1945. Printed by Druckhaus Tempelhof, Berlin-Tempelhof (1945)

- Lightning: The History of the 78th Infantry Division. Printed by Infantry Journal Press (1947)