Fort Shelby, also known as Fort Detroit, was an important installment during the War of 1812 that is often forgot about. Ownership of Fort Detroit bounced back and forth between Great Britain and the United States, including the American surrender of the fort in 1812. While this fort doesn’t seem like a pivotal installment in the war, the events that took place here represent the ongoing tug-of-war battle between the U.S. and Great Britain, and the passion with which the United States felt about the war.

The fort was originally built by the British in 1779, called Fort Lernoult. In 1796, the fort was ceded to the United States under the Jay Treaty. Later, in 1805, it was renamed to Fort Detroit. During the first campaign of the War of 1812, in August of 1812, British General Isaac Brock led an attack on Fort Detroit. American General William Hull was unprepared for the attack and instead of countering it, surrendered the camp to the British once they began to advance. Many believe this was an act of cowardice, and that the surrender, coupled with the abandonment of Fort Dearborn and Mackinac Island, left the Midwest exposed to the enemy.

The Americans reclaimed the fort in September of 1813 during the Battle of Lake Erie. The British army was forced to evacuate the Detroit frontier, leaving the fort under American possession. Upon repossession of the fort, Americans renamed it Fort Shelby. The winter following the repossession was exceptionally hard for American soldiers at the fort. Food and supplies were in short demand and many soldiers passed away, and over one thousand soldiers were put on the sick list.

Fort Shelby was constantly under a threat of attack until 1815 and the city of Detroit remained a bit shaken for some time due to the damage caused by the war. The fort remained garrisoned until 1826. Eventually, Fort Shelby saw it’s last days and was given to the city of Detroit to be demolished in the spring of 1827.

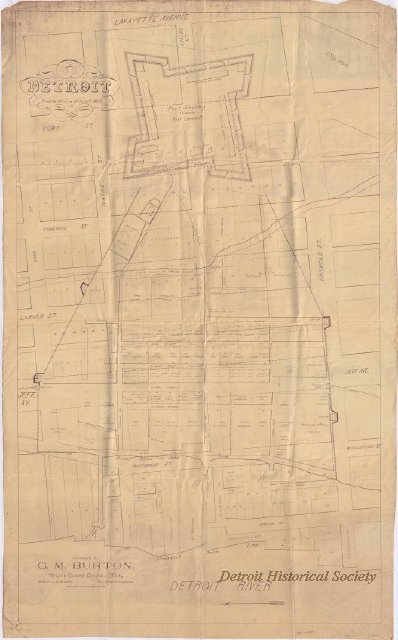

The fort, no longer standing, was situated in present day downtown Detroit, near the intersection of Fort Street and Shelby Street.

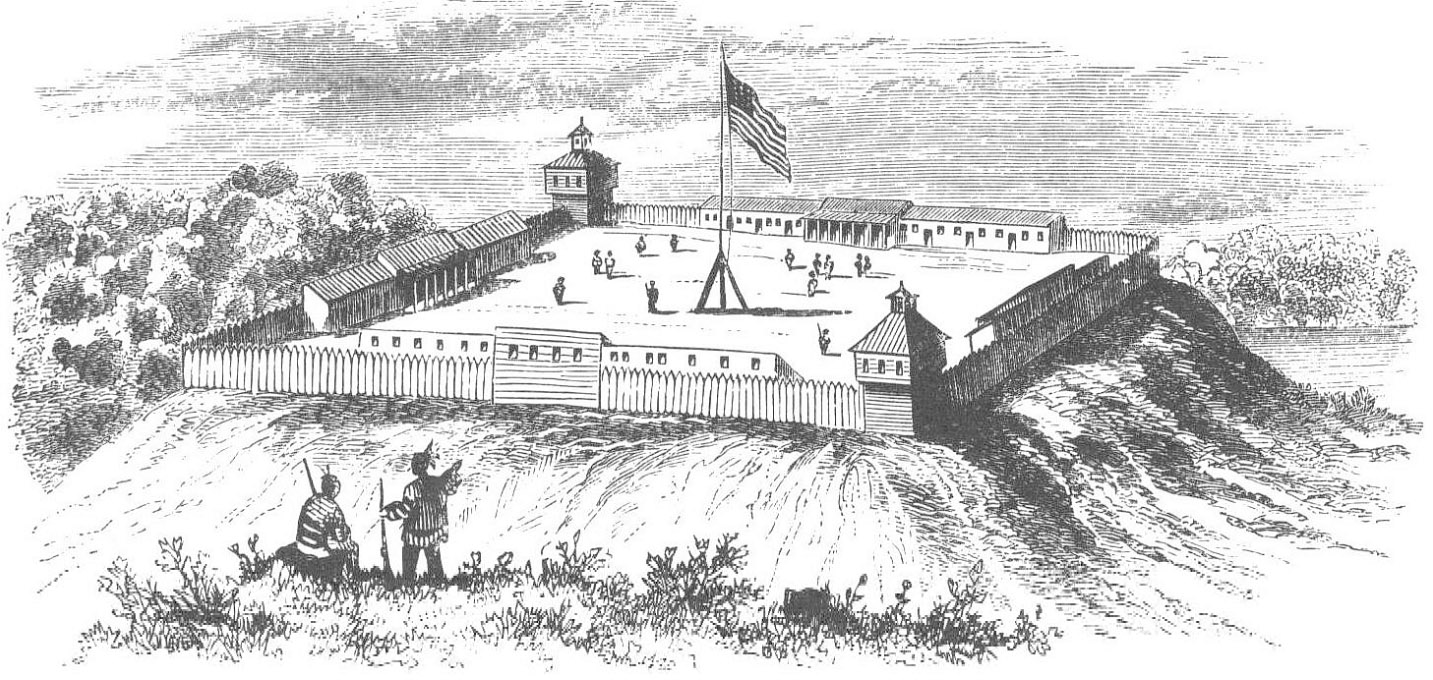

Fort Detroit before the War of 1812

Fort Lernoult was constructed by the British during the American Revolutionary War. Prior to war, Detroit was an up and coming supply depot and command center for outlying forts in the Northwest Territory. At this point, there were no major military threats to the British, so the area was weakly defended.

It wasn’t until the American rebellion and the impending threat of capture that the British decided they should better protect the area. British Major Richard Lernoult ordered his troops to install a new fort in Detroit in November, 1778. The 400 square foot structure was built on a hill outside of the city. The fort was surrounded by a fence as well as earth walls between 12 and 24 feet thick. The fort, when first constructed, could house 400 men and was armed with over 30 cannons.

During the Revolutionary War, Detroit was never attacked, and the fort was never put to use. The fort was supposed to be surrendered to the United States under the Treaty of Paris in 1783, but the British refused to surrender several outposts in the Northwestern Territory, and Fort Lernoult was one of them. It wasn’t until the Jay Treaty of 1796, 13 years later, that the British finally surrendered the fort and moved their troops to Canada. In July of that year, American troops began occupying the fort and started making improvements to the installment. The fort was renamed to Fort Detroit.

Fort Detroit during the War of 1812

During the War, Fort Detroit was a strategic outpost that didn’t see much action until August 15th, 1812. The fort was under the command of Brigadier General William Hull, who was the Michigan Territory Governor prior to the onset of the war. On this day in 1812, under Hull’s command, the fort surrendered to the British. This act was considered extremely cowardly, and many found it extremely shocking. The surrender of Fort Detroit is arguably the most memorable/historic event that happened at this site because of the pain and hardship that not only soldiers endured, but their wives and children as well.

Lydia B. Bacon, wife of Lieutenant Josiah Bacon, was in Detroit with her husband during the surrender of the fort. Mrs. Bacon had been keeping a journal during this time, and documented her thoughts during the surrender of Fort Detroit. On the 15th, the British prepared to attack under the command of General Isaac Brock after General Hull denied to surrender. On this night, Bacon writes,

“Never did a building come down faster in a raging fire than in the hands of these bloodthirsty fellows. The women and children are to go into the fort as the only place of security against the savage Indians, and the bombs, shells, and shot of the English…So I must lay aside my pen and escape to the place of safety, not knowing what shall befall me” (1856).

As Bacon discusses her flee to the fort under the attack, she mentions children of different ages, from a five year old boy, to a 14 year old teenage girl. Bacon writes that the British continue to bomb the fort until 1 o’clock in the morning. The next morning, Hull decides to surrender without attempting to fight back and effectively changes the lives of all the soldiers, wives, and children in the fort. Bacon describes the surrender:

“General Brock then sent to ascertain for what purpose the white flag was displayed, and learned the determination of General H. to surrender. Our soldiers were then marched on to the parade ground in the fort, where they stacked their arms…The American stars and stripes were then lowered from the flag staff and replaces with English colors” (1856).

Upon surrender, American soldiers along with some women and children were sent to Canada on a British vessel as prisoners of war.

It is important to take into account all the damage that the surrender of Fort Detroit caused in the United States, the soldiers at the fort, and the families at the fort. Lydia Bacon’s account of this incident gives great insight into the damage done to all people in the fort that night. Many men died that next and the next morning, several of which died gruesomely in front of children as young as five years old. The surrender also affected the United States’ stance during the war. As mentioned earlier, this surrender, coupled with the abandonment of Fort Dearborn and Mackinac Island, left the Midwest exposed to the enemy. It was due to incidents like these that neither side could gain an edge. Trying to win tactical battles was hard to accomplish when both sides surrendered so easily and ground/installments were constantly flipping back and forth between the entities.

General Hull’s Consequences for Surrender

Not only was Brigadier General Hull punished by becoming a prisoner under the British, he faced repercussions for his cowardly surrender after the war. General William Hull was sent to court under a number of accusations, including neglect of duty, cowardice, unofficer-like duty, and treason. The Report of the trial from 1814 indicates that Hull was sentenced to death, which was the punishment for treason, and also dishonorably discharged. In his Address, Hull argues this by comparing this sentence to that of England, and other earlier civilizations: “Are we then, Mr. President, in this country to be governed by rules which are derived from such a source, and have originated in such motives? Shall we adopt rules at which the sense, reason and humanity, of all mankind, since the civilization of the world, have revolted?” It is clear by these statements that Hull does not believe he deserves to die for what happened at Fort Detroit. President James Madison remitted the death sentence, and Hull lived the remainder of his life as an outcast disliked by many. While the sentence was remitted, Hull was the only General to be issued a sentence of death by an American court-martial.

In an effort to clear his name, General William Hull wrote two books titled Detroit: Defence of Brigadier General William Hull in 1814 and Memoirs of the Campaign of the Northwestern Army of the United States. In both books, Hull explains the situation as it unfolded and tries to get the American people see that there was not much more he could do. Even with these publications, Hull was never fully accepted by everyone. He even received a sort of “hate mail.”

A letter addressed to Hull in 1820, written by Timothy Walker, is an excellent example of the kind of harassment that Hull received following the surrender of Fort Detroit in 1812. In the beginning of the letter, Walker talks about how much he liked Hull as governor and was excited to see him as a Brigadier General. By the end of the letter, however, Walker doesn’t hold back when telling Hull that he would be better of dead. Walker gives Hull the following advice,

” …for you to stay no longer in Newton, but repair without delay to some unfrequented wilderness, where the footsteps of no human being ever before were seen; and where no voice is to be heard, but the hideous yells of ferocious beasts of prey, that are thirsting for your blood; and there in an humble, yea in a very humble, and penitent manner with deep contrition of heart, fall down on your knees, and endeavor, by your unfeigned and unceasing prayers and tears, to appease the wrath of an offended God, and if possible, obtain forgiveness for the sins that you have committed against Him and your country – and there remain a despised and miserable Troglodyte, until death shall end the scene” (10).

This long and verbally harsh sentence summarizes how many Americans felt about Hull after his surrender at Fort Detroit. Walker not only wished Hull to die, but he believed he deserved to suffer first, and that the suffering should be miserable. He also felt so strongly that he felt the obligation to write this letter to Hull, and followed it up with a second letter almost a year later, informing Hull that he was going to publish the letters so that the world could see them.

These accounts of the surrender of Fort Detroit in 1812, and the hardship faced by Hull following the surrender, portray the importance of this event during the war and in the history of the United States.

Recapture, Renaming, and Eradication of Fort Detroit/Shelby

In September of 1813, during the Battle of Lake Erie, Fort Detroit was handed back to the Americans. Under the command of General William Henry Harrison, 1,000 American troops advanced on Detroit and the British occupying the fort retreated back to Canada. On September 29th, the fort was renamed to Fort Shelby after the governor of Kentucky, Isaac Shelby, who aided Harrison with volunteer troops during the raid.

Following the war, Fort Shelby was occupied for 13 years. It then fell into despair and was given to the city of Detroit in 1826. In the spring of 1827, the fort was demolished as Detroit continued to grow into a big city full of life and commerce. As stated earlier, Fort Shelby was situated at the intersection of current day Fort and Shelby Streets.

To sum up, Fort Shelby has a history of back and forth ownership between the United States and Great Britain. Arguably the most prominent event to take place at this fort, was the Surrender during the War of 1812. This singular event and the reactions to it showed just how much passion Americans had for their country. The way the fort bounced back and forth, though, can also represent the actual war. Both sides struggled to make any gains in either direction, resulting in a war that was not beneficial for either country. In a similar way, Fort Detroit was pulled back and forth between the countries, and in the end, the fort didn’t make any gains either.

Primary Sources:

- Bacon, Lydia B. Biography of Lydia B. Bacon. Boston. 1856.

- Hull, William and James Grant Forbes. Report of the trial of Brig. General William Hull; commanding the northwestern army of the United States [microform]: by a court martial held at Albany, on Monday, 3d, January, 1814, and succeeding days. New York: Eastburn, Kirk and Co., 1814.

- Walker, Timothy. Two Letters Addressed to General William Hull; on his conduct as a Soldier, in the Surrender of Fort Detroit, to General Brock, without resistance, in the commencement of the late war with Great Britain. Boston: 1821.

Secondary Sources:

- Collins, Gilbert. Guidebook to the Historic Sites of the War of 1812 (2006): Dundurn Press.

- Dunnigan, Brian. “The Prettiest Settlement in America: A Select Bibliography of Early Detroit through the War of 1812,” Michigan Historical Review 27.1 (2001): 1-20.

- Farmer, Silas. The History of Detroit and Michigan or The Metropolis Illustrated. A Chronological Cyclopedia of the Past and Present (1884): Silas Farmer & Co.

- Rauch, Steven. “A Stain Upon the Nation?: Review of the Detroit Campaign of 1812 in United States Military History,” Michigan Historical Review 38.1 (2012): 129-153.

For Further Reading:

- Detroit Historical Society, Encyclopedia of Detroit.

- Online Encyclopedia, General William Hull Court-Martial.

- Wikipedia, Fort Shelby (Michigan).