The Mesabi Range, also known simply as the Iron Range to those who live there, is a collection of iron mines and mining towns in Northeastern Minnesota which made its name by becoming the single largest supplier of raw material to the World War II war effort. Without the Iron Range’s contribution, there may not have been American involvment in the Second Great War.

In 1939, Adolf Hitler and his Third Reich invaded Poland, and started what would soon become the Second World War, which would rage throughout the entire continent of Europe, into North Africa and across the Pacific Ocean. By the time 1940 rolled around, Hitler and his Nazis controlled most of Europe into France, except Great Britain and a few other neutral countries. With the coming of the 1939 war, bad news also brought hope to the struggling Minnesota Mesabi Range. With its economy in a desperate slump caused by the lack in demand of high-quality hematite since the end of the Great War, news of war soon brought hope to the Range and its miners, with thoughts of better pay and more secured jobs. When Congress lifted the arms embargo to Europe, mining companies decided it was time to bring their workers back from a long period of instability. When 9,000 miners were given jobs again, iron production on the Range increased from a measly 15 million tons in 1938 to 33 million tons of raw iron ore in 1939. With its production doubling in that one year, the steel plants in Gary, Chicago, Detroit, Toledo, Sandusky, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh received most of the Range’s ore, and refined it into whatever was required, pure iron and steel. This then went on to factories across the nation, to become the firearms, ammunition, and other war materiel that was soon shipped across the Atlantic to the French and British who placed their orders. By 1940, Mesabi Range was pumping out 49 million tons of iron ore, more than the previous two years combined. In fact, it was enough for the British and French by a long shot: “Between July 1940, and December 1941 American industry produced 1,341 naval ships, 136 merchant ships, 126.113 machine guns, 4,258 tanks, and 23,228 military aircraft.” (6, pg. 223).

Joan Reisinger, lifelong resident of the Range, recounts the story of her father working in the mines in approximately 1941.

“The average worker (on the Range) at this time had no idea what to expect. The nation had just been attacked for the first time since the British in the War of 1812 I believe. Some expected a draft, some expected no draft to hit the area. My father went from having to work eight hours a day to approximately fourteen to sixteen hours. We (my brother and I) hardly ever saw him. He was lucky when the draft came around, he wasn’t eligible to go fight in the war; in fact, he was considered indispensable to the war effort.” (Mary Joan Reisinger)

This was the case all across the Range when the draft hit in September of 1940. Although it was the country’s first ever peacetime draft, there was some concern when it came to the Range. The concern was not with the workers or government so much as it was with the mine owners. A larger draft from the area meant fewer men in the mines, and less men in the mines meant less product being put into train cars. (Although one can make the assumption that money was their first concern.) As the mines surrendered men to the “10 Million Man Army”, the mines opened to women employment for the first time. Just as women had won the right to enlist in the army, they had also gain the ability to mine the iron that would push America to victory.

Enter December 1941: The Range, being the first link in the chain of supplies to Europe was indeed the first to feel the change of the nation’s stance on the Second World War after the attack on Pearl Harbor. When America decided it was going to join the war, it little realized how much it had to build up. Just the year before, in fact, the United States had only been ranked 19th as a world power. When President Roosevelt ordered “Lend Lease” on the nation’s automobile factories and steel plants, forcing them to produce everything from tanks, fighters, ships, and bombers to firearms, canteens, and knives. The nation became one massive war machine, and at its heart and source, the Mesabi Range. Production on the Range increased dramatically, and so did morale. No longer was the average miner working for a paycheck, they were working for the United States. It was an act of patriotism to work six days a week with overtime. “In 1942 the industry produced 8,059 warships, 760 merchant ships, 666,820 machine guns, 23,884 tanks, and 47,859 military airplanes.” (6, pg 223). The total amount of iron mined during that year on the Iron Range was 188,310,000 tons of iron.

Over the next three years, while America’s troops pushed towards Japan in the Pacific and across Europe towards the heart of Hitler’s Third Reich in Berlin, the home front remained strong. Those who were able to stay in the mines did. Unlike in past times the inner-mine disputes, which had normally been handled by the mining company itself, were now under the jurisdiction of the United States War Labor Board. In fact, the miners signed a wartime no-strike pledge. This basically waived the labor laws impressed on companies for the duration of the war, however many workers had already upped their shifts and hours. The companies rewarded fabulously. Paychecks across the board increased, not by raises but simply by the sheer amount of overtime that the average worker was willing to put into his job to help his country. Not a single unpatriotic act or item could be found on the Range. There were no protests against the war, no one wanted to see the boom of the industry end. It has been said that war is a profitable business, and Mesabi Range may have been one of the most profitable areas of the war.

While the Mesabi Range had single-handedly supplied the iron for steel during World War II, it essentially dug its own grave. The Range totaled output of over 188 million tons of ore during the course of the war, and exhausted itself of natural hematite until the process of making taconite into iron was discovered into the 50’s and 60’s. The Mesabi Range lived like a star, dimly lighting the industry, and going supernova when it was most needed, provided for the country and gave everything it had until it had nothing left. In being the key for us winning the war, the Mesabi Range gave its life force, becoming just another casualty of the war.

Primary Sources

- Excavating Engineer Vol. 36, Num. 11 ( Nov. 1942) “Battleships are Born in Minnesota”

- The many personal documents and files of Anthony Francis Reisinger. (1931-1963) Private collection, assembled by Mrs. A.F. Reisinger, currently owned by Joan Reisinger. Viewed: 2015.

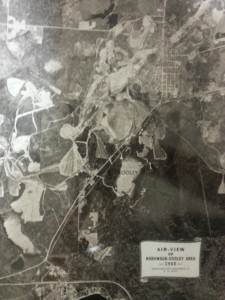

- “Air view of Nashwauk-Cooley Area” (1940) US Army picture.

- Reisinger, Mary Joan. (2015) Personal Interview, Nashwauk, Minnesota.

- Eastern Itascan (2003) My Old Hometown “Letters home from the 40’s” pgs. 55- 149

Secondary Sources

- Lamppa, Prof. Marvin G. (2004) Minnesota’s Iron Country. pgs.223-225

- Rosenman, S.I. (1942) Public Papers of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Vol. 1942.

- Melcher, Norwood B. (1941) “Iron Ore, Pig, Iron, Ferro-Alloys, and Steel” Minerals Yearbook 1941. Library of Wisconsin.edu.

- Walker, David A. (1979) Iron Frontier. MHS Press

Author’s Notes: I would like to thank Joan Reisinger for allowing me to view her collection of Anthony Reisinger’s documents, files, and pictures. At her request, files were not scanned but the pictures shown above from the collection are from that collection and used with her permission.