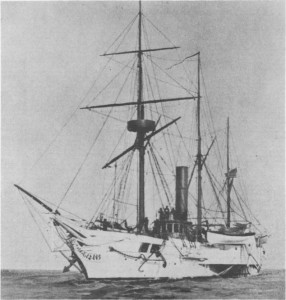

The USS Michigan was the first iron hulled ship of the U.S. Navy. The ship never fired a shot in battle but was a source of strength to the navy in the Great Lakes. The Michigan performed a variety of functions from storm rescue to being the only federal presence during miner strikes in the far reaches of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The USS Michigan participated in the arrest of a Mormon King and was once almost taken over by Confederate soldiers. The Michigan had her name taken from her and was renamed the USS Wolverine on June 17, 1905 before ending her career in 1923.

On August 3, 1841 the Senator from Ohio, William Allen, proposed setting aside $100,000 for steamers on Lake Erie (10). The Honorable A. P. Upshur, the Secretary of the Navy, made the decision for how funds would be spent. Some Congressman did not appreciate his choice of iron for the warship (10). In reply, Upshur sent a letter dated June 3, 1842 to the 27th Congress:

I determined to build this vessel from iron instead of wood, for two reasons. In the first place, I was desirous to aid, as far as I could, in developing and applying to a new use the immense resources of our country in that most valuable metal; and, in the second place, it appeared to me to be an object of great public interest to ascertain the practicability and utility of building vessels, at least for harbor defense, of so cheap and indestructible a material. (1)

Upshur defended his choice and the Michigan was launched in 1843. This was 18 years before the French La Gloire with iron hull and armor and 20 years before the iron-plated Merrimac and the iron hulled Monitor (6). Her home port was Erie, Pennsylvania where she made frequent stops. She stopped so often that many of the sailors married women from Erie, giving the city the nickname of “the mother-in-law of the Navy” (7). Many of the stories of such sailors are recorded. One biographical dictionary records the story of navy engineer Craig James Reid, a native-born of Erie, whose daughter married Dinwiddie Borthwick, also an engineer in the navy, and whose family, including Robert Reid graduated from the naval academy (2, 575). Craig Reid moved from ship to ship while he was in the navy and served aboard the Michigan from December 1880 to July 1883 (2, 575). It is family stories like these that show how intertwined the life of navy sailors in the Great Lakes was with this Lake Erie port and its people.

The creation of the Michigan was during a controversial time of British-American relations. The Canadian Rebellion of 1837 showed that a stronger military presence was needed in response to two military steamships the British had made (5). The Michigan was also useful in dealing with bands of rebels, whether they originated from the American or Canadian side of the water (11). The year she was launched was during the time of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty that resolved a time when British sailors sailed onto U.S. waters, captured the ship Caroline, and burned the ship.

One early exploit of the Michigan was with a man who called himself King James I. James Jesse Strang was one of the 12 Elders of the Mormon Church who split apart from the existing church and founded a settlement in Illinois in 1849. Later he would crown himself King and Ruler and would move to Beaver Island in Lake Michigan in 1847 (10). He would become known as King James I, the only monarch ever crowned in Michigan. In May 1851, arrest orders were given and the USS Michigan with Captain Bullis in command picked up a District Attorney at Detroit on its way to Beaver Island to arrest King James I (10). King James I surrendered and charges were later dropped. Later, on June 19, 1866, two followers of King James I assassinated him and went to the Michigan, resting in the water nearby, for a safe haven (8). The Michigan took them to Mackinac City where they were released without charges (8).

The Michigan was a vessel of rescue as well as capable of war. There were many incidents of ships in the Great Lakes running aground, becoming ice-stranded or caught in a storm, and frequently suffering equipment breakdown. The Michigan was able to help with many of these problems due to her powerful engines and damage-resistant hull. Examples of these rescues include the paddle steamer Mayflower which was rescued from shoals in 1850 and 1852, the Golden State which ran aground near Erie Harbor in 1856, and the Sunshine which capsized off Long Point in 1859 (9). Sometimes, as in the case of the Sunshine, the rescue could not be made in time and the crew had the responsibility of bringing the bodies back to land for burial.

In 1864, the Michigan was stationed off of Johnson’s Island where Confederate prisoners were held. John Yates Beall with 19 Confederates captured the Philo Parsons steamer (8). Their plan was to head to Johnson’s Island where they would be signaled by Captain Charles H. Cole, an agent for the South who had been talking to the officers of the Michigan (8). If the plan succeeded then the Confederate prisoners could be released and the Michigan used as a raider in Union waters. This would be particularly effective as there were no other American warships on the Great Lakes. Unfortunately for their plans, the Michigan’s Commander Carter realized Cole was working for the South and had him arrested. The Philo Parsons arrived at Johnson Island but, after not receiving any signal from the Cole, gave up and returned to Sandwich, Canada.

During the second half of the 19th century, the Michigan played a large part in acting as a sign of federal authority. Shortly after the Civil War, the economy was thrown into chaos with wages being cut and workers laid off. This created a condition of turmoil where riots were widespread. The “Peninsula War” of 1865 resulted in strikes by iron miners in Marquette and copper miners in the Houghton-Hancock region (9, 97). The Michigan had recently taken on a new commander, Lieutenant Commander Francis A. Roe, who had served in the Civil War and shown himself to be a fearless and tactical officer. When Roe arrived in Marquette on July 3 on a patrolling mission, he found the town in an uproar. The miners had gone on strike and were destroying property in the town. In mining boomtowns, there was frequently little police force other than managers of the mining company. After the recent bloody war, the Federal government seemed to be a long way away from the remote Upper Peninsula. Roe, a man of action, took two twelve-pounder howitzers on a railroad platform car and a naval escort to meet the miners. After the surprising arrival of the sailors showed that the government had a presence in the area, Roe gave the miners 24 hours to get back to work and desist the threats of violence or the guns would be used on them. The miners went back to work the following morning.

Roe and the Michigan continued on to Houghton by means of the Portage. The ship was able to squeeze through the as yet unimproved channel due to her shallow draft. After arriving at Houghton on July 8, Roe found the area in a similar situation to Marquette. This time, the Michigan was limited in her firepower by the steep terrain of the Keweenaw Peninsula. Roe chose a new tactic. Instead of bringing his weaponry to the miners, he invited any of the public to come aboard and view the ship’s weaponry. This tactic, along with a press release and several firing demonstrations, served to convince the local miners that the Federal government did indeed have a presence on the far reaches of the Upper Peninsula.

After Houghton, Roe returned to Marquette on July 13 to find that the miner’s strike had renewed. This time the miners had blockaded the railroad lines to all but passenger trains, limiting use of the Michigan’s guns. In response, Roe telegraphed the Army to come and provide assistance. The 8th Veteran Reserve Corps infantry company arrived on July 15 (9, 102). Caught between the Army and the Navy, the miners held on for a short time before ending the strike due to pressure from the two forces.

The worker strikes and direct military involvement in such affairs was not uncommon during this time. There was a precedent of martial law from the Civil War and which continued to the miner strikes involving the Michigan. In 1864, General Roscrans was the military adjutant in Missouri. In the city of St. Louis, workers’ wages had increased significantly. Wages were $1.50 a day for mechanics in 1861 and in wartime had risen to between $3.50 and $4.00 a day (4, 78). During 1864 some shops began to hire large numbers of apprentices. The journeyman mechanics, wanting to keep wages high and suspecting that shop owners were attempting to create a worker surplus, started organizing strikes against these shops and harassing workers that did not help. Many of these shops had government contracts. Urged by the shop owners, General Rosecrans issued General Order No. 65 on April 29, 1864 which forbid striking and threatened the use of military force, particularly for such establishments where as the original document says, “the operations of some establishments where articles are produced which are required for us in the navigation of the Western waters, and in the military, naval and transport service of the United States” (3). The order also requested the names be presented of those who participated in the strikes. Military force was applied to enforce the order. The workers responded with this petition:

We could believe you never would have promulgated Order No. 65, but for reasons of military necessity, and as loyal men we regret if the operations of the Government have been impeded by the course of those mechanics interested felt called upon to take… we invite you to issue an order requiring the “bosses” to limit the number of apprentices to one for every five journeyman employed in their establishments, thus ending the controversy, and, as we believe, on the side of justice. (4, 78)

This petition indicates the level of authority the military had during this time. Martial law was very much in effect as shown by the relative strength of the military forces compared to the presence of the local police force which was little to none. The mechanics’ petition did not hinge on whether the application of military force was moral or correct but focused on requesting that General Rosecrans adjust his stance to aid the workers. With this incident as precedent and with the limited military support in the Great Lakes region of the U.S., it is not surprising the course of action that Lieutenant Commander Roe took with the forces at his disposal. Similarly to the iron and copper miner strikes, these cogs of the economic wheel helped supply the military. Both the army commander and the naval commander took steps which dealt harshly with any disturbance to the general peace or to the logistical supply chain.

The Michigan was renamed the Wolverine in 1905 after her original name was desired for Battleship No. 27 and she was then assigned as a Miscellaneous Auxiliary, IX-31 in 1920 (8). During the period of 1912-1923 she was used in training with the Naval Reserve. After 1923 a connecting rod broke and her active career was ended. Not enough funds were raised to restore her so she was scrapped in 1949 with her bow and cutwater set up as a monument near the shipyard where she was built in.

Primary Sources

1. House Documents, 13th Congress, 2d Session-49th Congress, 1st Session 3 June 1842

2. Whitman, Benjamin. Nelson’s Biographical Dictionary and Historical Reference Book of Erie County, Pennsylvania. Erie, PA. : S.B. Nelson, 1896.

3. The Civil War in Missouri. 1864 Labor Unrest and General Order No. 65.

4. Parrish, William E. A History of Missouri Volume III 1860 to 1875. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1973.

Secondary Sources

5. History and Memorabilia Erie Pennsylvania. USS Michigan – USS Wolverine.

6. MORE PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE U.S. STEAMER MICHIGAN ProQuest SciTech Collection, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 38-40, 2008.

7. Robb, F. Gridley will again fire when ready Knight Ridder Tribune Business News, p. 1, 11 February 2006.

8. Radigan, J.M. Wolverine (IX 31) ex-Gunboat Michigan

9. Rodgers, Bradley A. Guardian of the Great Lakes: The U.S. Paddle Frigate Michigan. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1996.

10. Spencer, H.R. USS Michigan USS Wolverine, Erie, PN: Erie Book Store, 1966.

11. Warnes, Katherine. “THE USS MICHIGAN – THE FIRST IRON SHIP OF HER AGE.” Veterans Today 17 October 2015

Further Reading

MHUGL: “The USS Michigan”

Erie, PN History and Memorabilia Site

Wikipedia USS Michigan (1843)

NavSource Wolverine ex-Gunboat Michigan