Overview

William Tecumseh Sherman, was born February 8, 1820, in Lancaster, Ohio. When Sherman was nine years old his father, a successful lawyer on the Ohio Supreme court, unexpectedly died in 1829. From then on Sherman lived with his family’s neighbor and friend, Senator Ewing. When Sherman reached the age of sixteen, Ewing secured Sherman an appointment to be a cadet in the United States Military Academy at West Point, and so Sherman’s time in Ohio came to an end. Years later fighting on the side of the Union Army, Sherman worked as a General and became well known through his use of total war in subduing the Confederate States. Sherman’s March to the Sea (or the Savannah Campaign), highlights the conduct Sherman was willing use and was a major Union success in pushing the Confederacy towards surrender.

After the battle of Chattanooga on June 8, 1862, the Confederacy was feeling quite weakened under the pressure of advancing Union forces, and soon the Confederate States would be at risk of being cut in half by the forces of Sherman. Sherman eventually forced the Confederates out of Atlanta in September of 1864. It is at this point Sherman sought a way in which he could checkmate Confederate General John Bell Hood, and ultimately concluded that a march through Georgia, ending at the sea severing the heart of the Confederacy. This strategy, which was met with disapproval by some Union leaders, such as General George Thomas, as well as some apprehension from Ulysses. S. Grant, but ultimately when Hood began to cross the Tennessee river with the aim of invading Tennessee, Sherman convinced Grant of the plan and was dispatched the message “Go as you propose”(5: 466).

Having finally finalized his choice to march into the depths of the Confederacy, and trusting in Thomas to hold Tennessee from an advancing Hood, Sherman sent a final message simply stating “all right,”(5: 241), and began his march towards Savannah, now cut off from any Union support in the North. Thus on the morning of November 15, 1864, two wings of almost equal strength began the 300 mile journey towards the sea to the southeast, with a total strength of around sixty-two thousand men. Ultimately Sherman and his men encountered little resistance as they steadily marched to Savannah, and after twenty anxiety inducing days of marching in unknown areas they saw the sea they were marching towards in the distance.

Having successfully reached the sea as he had hoped, Sherman’s next task was to do away with the Confederate forces holding Savannah. This meant taking Fort McAllister, which was “bristling with heavy guns, and armed with heroic men” (7:243). Despite such a situation, Sherman ordered an assault on Fort McAllister as nighttime began to approach, and on December 13 a division of Major General Hazen’s blue coats moved steadily towards the fort. Even with artillery, the explosion of hidden torpedoes, and musketry fire coming from the fort, the Union forces would quickly breach through the Confederate’s defenses. In a mere fifteen minutes, Sherman assaulted and captured Fort McAllister. This allowed for communication to be made with the Union fleet, and with the withdrawal of Confederate troops from Savannah followed by the city’s Mayor proposing a surrender to the Union troops on December 20, completed the second step in Sherman’s march. More than this, Sherman had not spared anything that might support the Confederate’s ability to fight throughout his march. Railroad infrastructure, bales of cotton, cotton gins, machine-shops, among many other tools of industry were burned or destroyed by Sherman’s men. Alongside such destruction, Sherman’s men known as “bummers”, foraged and seized food and supplies from local farms. Along with helping to hinder the Confederacy’s ability to supply its army, these actions also served to heavily demoralize the people of the Confederacy who were at the mercy of Sherman and his men.

In the months to follow Sherman’s success at Savannah, he looked to complete his turning movement and face what remained of Lee’s army alongside Grant and his troops. At this point what remained of the Confederate army was dwindling, both in man-power as well as fighting spirit, and Sherman’s movement into the South had only further hurt their ability to fight. Thus Sherman made his way through the Carolinas with ease, continuing to employ his belief in total war by leaving destruction in this path. Eventually Sherman accepted the surrender of Confederate General Joseph Eggleston Johnston on April 26, 1865 in North Carolina. With Lee having surrendered to Grant’s forces earlier in the month, this marked the end of Sherman’s movements in the South, and the war itself was coming to a close. In the end Sherman’s choice to move into unknown enemy territory whilst having no communication with his allies, proved a stunning success for the Union. It is not without criticism however, as Sherman’s actions relating total war would leave great antipathy in many who lived in the Confederate states that were subject to his might.

The Effect of Total Warfare

While it is clear that Sherman’s movement through Georgia was successful with regards to capturing Fort McAllister and essentially splitting the Confederacy into two, there is still the question of the success of his employment of total warfare on the state of Georgia and the Confederate followers living in it. An example of a typical Georgian whose life was effected by Sherman’s march to Savannah is the experience of Dolly Lunt Burge, a woman taking care of her plantation in Georgia when Sherman marched through Georgia. As Sherman’s men moved through the area, Dolly Burge describes the actions of the Union soldiers as barbaric: “like famished wolves they come, breaking locks and whatever is in their way”, and “My eighteen fat turkeys, my hens, chickens, and fowls, my young pigs, are shot down in my yard and hunted as if they were rebels themselves” (1:23). In the midst of Sherman’s march, she exemplified the terror she felt towards the Union soldiers stating, “I could not close my eyes, but kept walking to and fro, watching the fires in the distance and dreading the approaching day, which, I feared, as they had not all passed, would be but a continuation of horrors”(1:22). While this fear could be seen as a victory in regards to crushing the Confederate spirit, the final thought of Dolly Burge as Sherman’s army finished passing through was that, “A few minutes elapsed, and two couriers riding rapidly passed back. Then, presently, more soldiers came by, and this ended the passing of Sherman’s army by my place, leaving me poorer by thirty thousand dollars than I was yesterday morning. And a much stronger Rebel!”(1:34).

It would seem then that while part of Sherman’s aim in moving through Georgia with unbridled might was to deter the civilians in the seceding states to cast out their loyalty to the Confederacy, it often had the opposite affect. This aim can be seen clearly in one of Sherman’s letters to General Henry Halleck, wherein he puts for the idea that “We cannot change the hearts of those people of the South . . . but we can make war so terrible that they will realize the fact that, however brave and gallant and devoted to their country, still they are mortal and should exhaust all peaceful remedies before they fly to war” (3:126). Unfortunately for Sherman this did not seem to be the typical response of those who saw the devastation in the wake of his march, as can be seen with Dolly Burge. Instead the resolve of the Confederate rebels Sherman sought to demoralize simply grew increasingly spiteful towards Sherman and the Union troops, only feeding the flame of rebellion. A similar result was seen when Sherman moved through the Carolinas following his successful capture of Savannah. South Carolina is described as being “plunged into the purgatory of defeat, conflagration, and utter despair. The march through Georgia was, in comparison, a mere maneuver” (8:699). As it had been in Georgia, those in South Carolina who suffered from Sherman’s total war style fighting came away not with shaken resolve in the Confederacy, but rather a strengthened resentment for Sherman and Union he fought for. That being said, it would be inaccurate to insist that Sherman’s march was wholly ineffective in his aims to demoralize the enemy. Sherman himself wrote to Halleck in December 1864:

We are not only fighting hostile armies, but a hostile people, and must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war, as well as their organized armies. I know that this recent movement of mine through Georgia has had a wonderful effect in this respect. Thousands who had been deceived by their lying newspapers to believe that we were being whipped all the time now realize the truth, and have no appetite for a repetition of the same experience(4:227).

Clearly, at least from the perspective of Sherman, the efforts to crush Confederate resolve was not an entirely unfruitful endeavor. That said, the strengthening resentment for the Union that seemed to be a common result of Sherman’s actions would indicate that the battle over the strength of will of those in the Confederacy was not where the true potency and effectiveness of Sherman’s march and his employment of total warfare resides.

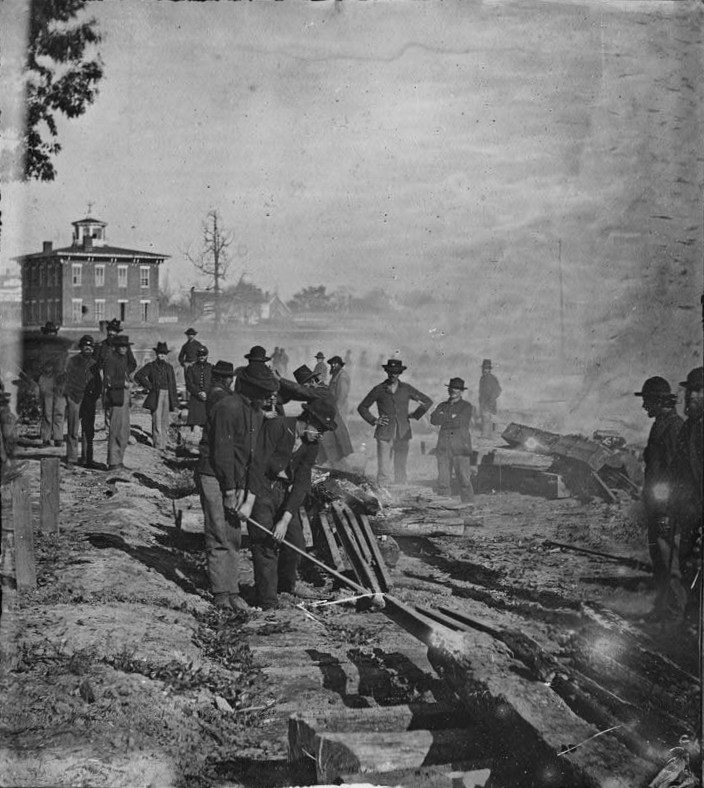

What was it then, which made Sherman’s March to the Sea of such significance? The answer to this lies in the other half of what total warfare achieves, not the destruction of people’s spirits but rather their resources. Even if the people of the Confederacy did not lose their spirit to fight, Sherman made it his goal to deny them any resource that could aid the Confederacy’s fight against the Union. Of the most important of such resources is that of railroads, as with connected and working rail lines came better logistical support, an important factor in being able to proper be supplied and continue fighting during the war. Thus railroads became key targets for Sherman, and his time at the city of Meridian exemplified his determination to crush tools such as railroads, among other assets, that could aid the Confederacy. Sherman describes his men’s efforts in Meridian saying, “For five days 10,000 men worked hard and with a will in that work of destruction, with axes, and crowbars, sledges, clawbars, and with fire, and I have no hesitation in pronouncing the work as well done”(2:173-79). Sherman’s destruction in Meridian went beyond railroads, but also depots, store-houses, hospitals, arsenals, and many other assets that were deemed of potential use to the Confederacy (10:471). The treatment of Meridian is not an outlier, rather the typical treatment of the cities who met with Sherman during his march, as well as the South Carolinian cities afterwards. The sheer amount of destruction that Sherman managed to inflict upon large portions of the Confederacy quite clearly inhibited an already dwindling army’s ability to fight. Logistically, the Union had already had the upper hand, and following Sherman’s March to the Sea this was only made even truer. So while Sherman’s embracement of total warfare may have turned many Confederates to even greater supports of the Confederacy, he also ripped from them any means in which they could legitimately oppose the Union. This is where the great success in Sherman’s actions lie.

Beyond The Civil War

It is also worth looking beyond the scope of the end of the Civil War to see why else Sherman’s March to the Sea holds importance. The first is that while it is clear that Sherman’s actions hastened the war’s end, it did so in spite of the aim of the war. Ultimately the Union wanted to bring back into the fold the states that sought to secede, yet due to Sherman’s actions this was half accomplished. While the Confederate states did in fact return to the Union, several, namely Mississippi, Georgia, and South Carolina,they did so with deep wounds that would remain unhealed for generations (10:480). Forgiveness for their treatment during the Civil War took these states no small amount of time, and even still some might look back painfully at the destruction their State once suffered. Such wounds certainly did not help when guerrilla warfare sought to resist Reconstruction following the conclusion of the Civil War. Beyond even the scope surrounding the Civil War itself, it is also important to note the implications Sherman’s actions had toward warfare as a whole. Sherman’s March to the Sea was the first military action of the United States that could be said to employ total warfare, but over time such a view of warfare would become the standard in United States conflicts in the twentieth century such as the first or second World Wars.

Primary Sources:

- Burge, Dolly L. A Woman’s Wartime Journal: an Account of the Passage over Georgia’s Plantation of Sherman’s Army on the March to the Sea, as Recorded in the Diary of Dolly Sumner Lunt (Mrs. Thomas Burge). New York. The Century Co., 1918.

- Sherman, William T. Sherman to Rawlins, March 7, 1864, in Official Records,Ser. I, Vol. 32, Part 1, pp. 173-79.

- Sherman, William T. Memoirs, 2nd ed, 2 vols. (New York, 1886), II, 126 -127.

- Sherman, William T. Memoirs, 2nd ed, 2 vols. (New York, 1886), II, 227.

Secondary Sources:

- Rhodes, James Ford. “Sherman’s March to the Sea”. The American Historical Review 6.3 (1901): 466–474.

- Hume, Janice, and Amber Roessner. “SURVIVING SHERMAN’S MARCH: PRESS, PUBLIC MEMORY, AND GEORGIA’S SALVATION MYTHOLOGY.” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 86.1 (2009): 119-37.

- Byers, S. H. M.. “The March to the Sea”. The North American Review 145.370 (1887): 235–245.

- Milton, George Fort. The American Historical Review 57.3 (1952): 699–700.

- Tucker, Glenn. The Florida Historical Quarterly 50.2 (1971): 193–195.

- Walters, John Bennett. “General William T. Sherman and Total War”. The Journal of Southern History 14.4 (1948): 447–480.

For Further Reading: