The US gun-brigs Lawrence and Niagara were sister battle ships built for Master Commander Oliver Hazard Perry’s fleet to fight the British Navy on the Great Lakes in the War of 1812. Being sister ships, they were built in tandem at the Cascade shipyard to be identical. Each was a 118 foot, two-masted ship built with thick oak, with 18 32-pound carronades, which were short, smooth short range cannons, and two long-range 12-pound long guns. The Lawrence was named after James Lawrence, a sailor who inspired Perry, that died battling the British in Boston Harbor.

The construction was not without it’s troubles, however. The enemy ships, Queen Charlotte, and Lady Prevost were already on their way to the Harbor that Perry was stationed at, and there were not nearly enough men to man the ships for battle. Perry at this time was under the command of Commodore Isaac Chauncey, who moved the majority of his men to Lake Ontario, leaving Perry with little support. The ships themselves were built using improvised materials. Due to a lack of iron, much of the hulls were held together with wooden pins, also knows as “tree nails.” To make them watertight, the hulls were caulked with lead, instead of oakum and pitch. These techniques worked quite well, and the ships that would have taken a year to construct were done in a matter of 8 months. Fortunately for Perry, in July more men came as volunteers in his fleet, and iron supplies had finally arrived. They were used to make tools for the crew and ammunition for the cannons. Men from Buffalo and Erie came in their own private vessels to sell goods and supplies unofficially, encouraged by the high prices they could get from Perry’s men.

On August 4, Perry had his fleet towed to the entrance channel to Lake Erie, and chose the Lawrence as his flagship, and took along his now-famous flag bearing the phrase “Don’t give up the ship”, which happened to be James Lawrence’s last words. Luck held out again for Perry, for the British held back on engaging them while they were setting up and in a vulnerable state, thanks to the cover of trees and mist on the lake that obscured the British commander Barclay’s vision. On the night before the engagement, Perry issued written orders to each of his captains, telling them to sail at a distance of 300 feet from eachother, and what ships they should each engage; the Niagara was to oppose the Queen Charlotte, and the Lawrence was to engage Barclay’s flagship, the Detroit. Knowing that the British had an advantage at long range, Perry instructed his commanders to get as close to the British as possible in order to get the full effect of their superior short carronades.

The Battle

In the first stages of the battle, Perry moved forward to engage the British on the Lawrence, where the British navy focused their long-range guns on him and battered the ship into a bulk easily. Still, the Lawrence steadily advanced to close the gap between her and the Detroit, which took half an hour. But Perry’s second in command, Jesse Elliot, who was in charge of the Niagara, didn’t move forward with the rest of the ships. Instead, he remained outside the range of his designated opponent, the Queen Charlotte. This caused the Charlotte to move ahead, and join Barclay’s flagship in attacking the Lawrence.

For a full 90 minutes the British ships wreaked havoc on the Lawrence. The scene on Perry’s ship was a gruesome one; blood, brains, hair and bone littered the deck, and crewmen witnessed their comrades being exploded by cannonballs right in front of them. Still Elliot hung back, and Perry’s men would die wondering where the Niagara was. At 2:30 pm, none of the flagship’s guns worked, and the sails could hold no wind.

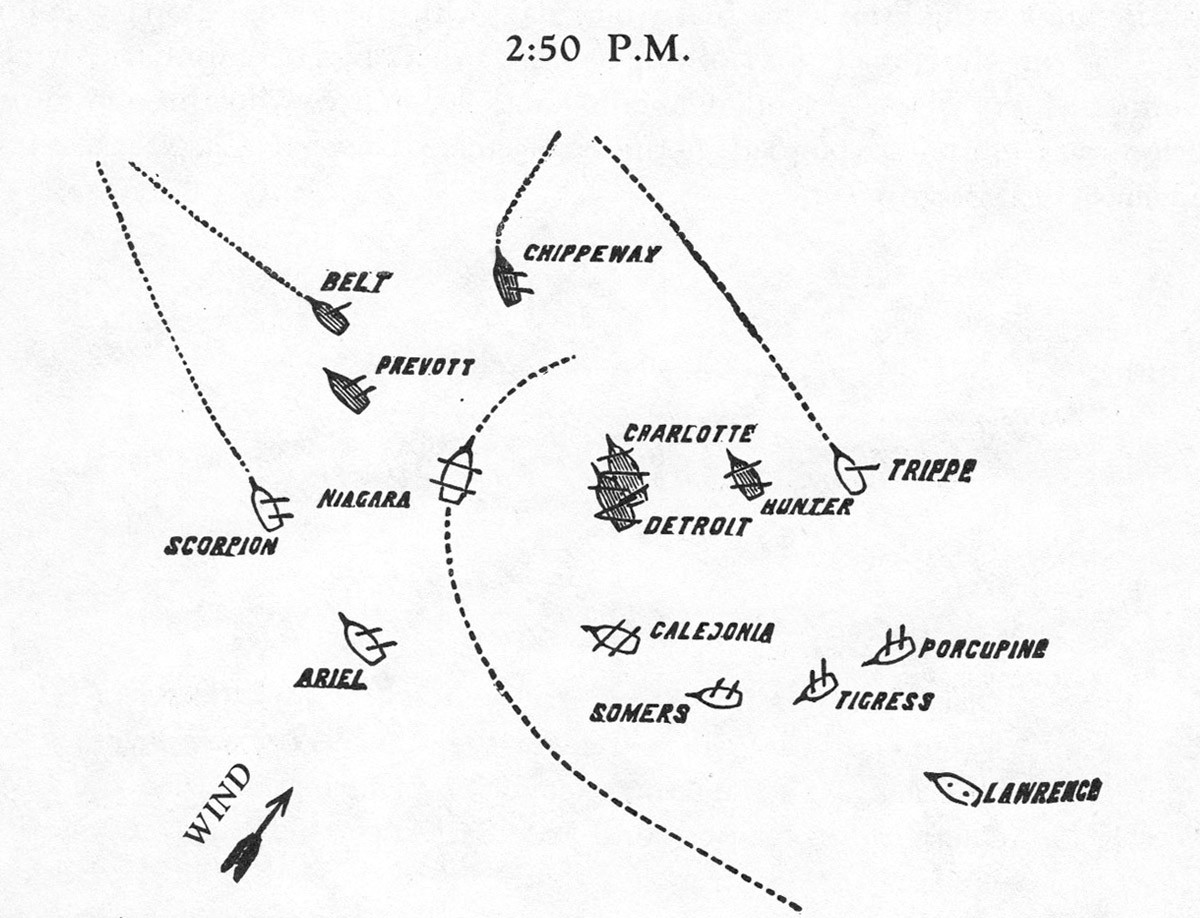

Perry was ready to surrender, and at that moment Elliot brought his ship up into close combat. Perry then made the decision to move to the Niagara by rowboat, accompanied by 4 of his crew, and assume command of it. While Perry captained the ship, Elliot was tasked with taking a rowboat to regroup with the rest of the American fleet. Perry ran up his battle flag while the Lawrence surrendered in the distance. Perry decided that with their superiority in firepower, the best course of action was to go in hard and fast. He maneuvered the Niagara to cut between the British line of formation, so that the Lady Prevost and Chippewa were on the left, and the Queen Charlotte and Detroit were on his right. The British saw the Niagara drawing near, and in their haste to take evasive action, the Charlotte fouled the Detroit, causing their rigging to get tangled, and the two ships were stuck together.

Perry ordered the cannons on both sides of the ship to be loaded, sailed the Niagara between the four British ships and fired from both sides. Once between them, the Niagara spilled the wind from her sails, remaining in place and launching volley after volley, raking the entire length of the British ships. Meanwhile, Elliot had succeeded in regrouping the rest of the American fleet, and they continued firing their heavy guns at the British as well. They caused enough damage to the remaining ships to make the entire fleet surrender. Within 15 minutes of the Niagara’s first broadside, an officer on the Queen Charlotte started waving the white flag. Immediately after, the Detroit surrendered as well. Hunter and Lady Prevost also lied vulnerable and surrendered rather than have the Niagara shoot at them. The two smallest British ships tried to get away, but also surrendered once the American schooners caught up with them.

The Aftermath

The Americans took possession of each of the British ships, and were tasked with guarding the prisoners and repairing the vessels enough that they could get back to shore. The next morning, the dead from both sides were committed to Lake Erie, and a funeral was held with both Americans and British in attendance. The wounded were taken on-board the Lawrence, and treated by the British and American surgeons. After repairs, she was sailed to Erie as a hospital ship during the rest of the war. The Niagara continued service throughout the rest of the war for patrol and convoy duty, and pursuing retreating British ships. It wasn’t in good enough condition to fight after that, so it was used as a receiving ship for new sailors in Erie until 1820, housing them until they were ready to board a battle-ready vessel.

Following the declared demilitarization of the American-Canadian border at the end of the war, both ships were intentionally sunk to the bottom of Misery Bay; the Lawrence in 1815, and the Niagara in 1820, where the cold water would preserve the hulls, should they ever be needed again. While still submerged, the Lawrence was sold in 1825, but wasn’t raised until 1875, except for a brief examination in 1836. In 1875 it was cut into pieces, and transported to Philadelphia by rail, and shown at the 1876 celebration of the United States Centennial. During the exhibition, the Lawrence was displayed outside a warehouse, where it was being cut up for relics. Unfortunately, during the exhibit, the warehouse caught fire one night, and the ship’s remains were destroyed.

The Niagara was raised in 1913, by the Perry Victory Centennial Commission, and restored by a group of Erie citizens for the Battle of Lake Erie centennial. The original plans were lost however, and the Navy Department and National Archives couldn’t find them, so the restoration was based on a new design by naval historian Howard I. Chapelle. It was then towed around to various ports on Lakes Huron and Michigan for activities.

The ship became property of Pennsylvania in 1931, and was about to undergo another restoration, but it was halted in 1934 because of budgetary difficulties cause by the Great Depression and World War 2. The restoration finally finished in 1963, just in time for the sesquicentennial celebration of the Battle of Lake Erie. At that point the ship was on concrete blocks at the foot of State Street in Erie. Again the ship fell into a state of disrepair in the late 1980s, and ship designer Melbourne Smith was in charge of the restoration. The ship was disassembled in 1987, and then reassembled in 1988. On September 10th that same year, the ship was involved in launching ceremonies to commemorate the 175th anniversary of the Battle of Lake Erie. Niagara was moved to Holland Street, and it’s latest renovation was finished in 1990, where it once again became safe to sail.

There are a few changes from the original design, however. It is slightly longer in length, and the yellow pine mast has been replaced with a Douglas fir one. Today, the Niagara is a fully restored sailing ship. It is owned and operated by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, and is the Pennsylvania state flagship. She is one of only three U.S. vessels remaining from the War of 1812, the other two being the U.S. Frigates Constellation, and Constitution. And she is the only remaining vessel of her class. It sails the Great Lakes with a crew of 20 full-time sailors and 20 volunteers, and is featured on the National Register of Historic Places.

Primary Sources

- Altoff, Gerry T. “Oliver Hazard Perry and the Battle of Lake Erie”. Michigan Historical Review 14.2 (1988).

- Barry, James P. (1970). “Battle of Lake Erie, September 10,1813”, from Focus Books.

- (1813). “The Documentary History of the Campaign Upon the Niagara Frontier“, from Lundy’s Lane Historical Society.

- Edited by Rybka, Walter and Heersen, Wesley. “US Brig Niagara: Crew Handbook”, from Flagship Niagara League.

Secondary Sources

- Stauffer, Bobby (2009). The Brig Niagara, from Pennsylvania Center for the Book.

- (1979). “Battle of Lake Erie: Building the Fleet in the Wilderness”, from Naval Historical Foundation.

- The Fleet,(2015) from Lake Erie Heritage Foundation.

- US Brig Lawrence, (2015). from History and Memorabilia.org.

- Naval Battleships in the War of 1812, (2011). from PBS.org.

- Snyder, Rod (1998). “Erie Maritime Museum, Volume 24, Number 4“. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

- Swedin, Eric G. (1997). “War of 1812: Battle of Lake Erie- Oliver Perry Prevails“, from Military History, Magazine.