The Civil War, a bloody conflict that engulfed the entire nation, fought by ordinary men who accomplished the extraordinary. Forever immortalized in monuments, these men came from the same towns as you and me. The 17th Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment mustered in Detroit only to fight all the way to Union victory. These valiant men became legend in their first engagement at South Mountain, earning the title “The Stonewall Regiment”.

Volunteer to Valor

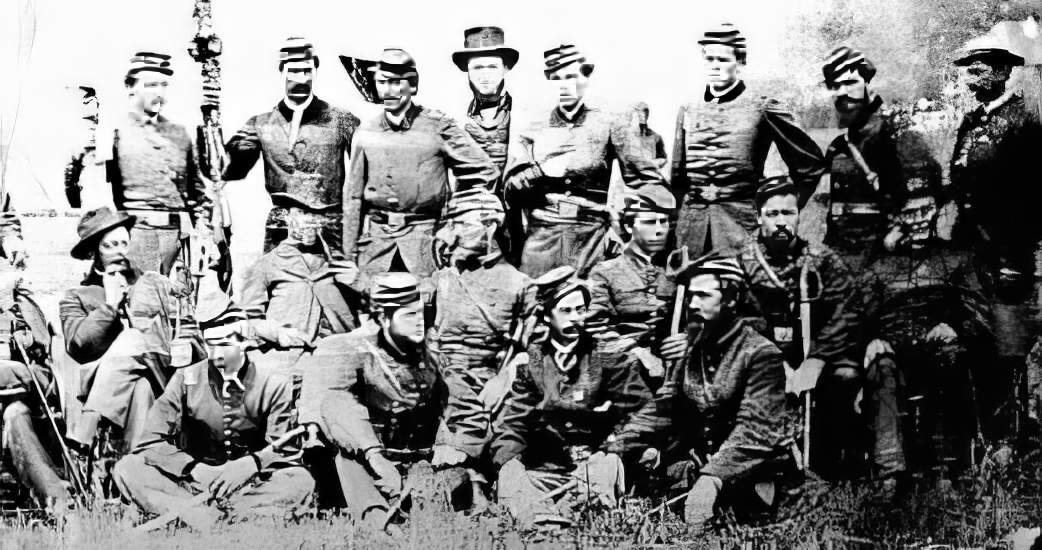

The spring of 1862. The men mustered at Detroit from the surrounding, towns ranging from farmers to students. Nearly one entire company was comprised of students from the Michigan State Normal School which would later become Eastern Michigan University. Under the command of Colonel William H. Withington, the regiment marched to Washington, D.C to join the First Brigade of the Ninth Corps under the command of General Jesse L. Reno.

Upon arrival they immediately moved with the Army of the Potomac to confront the confederates marching into Maryland. Having been out of the state of Michigan for less than two weeks, the men were ill prepared and unaware of the danger they would face. Their fate, it seems was to simply offer the Confederates a target.

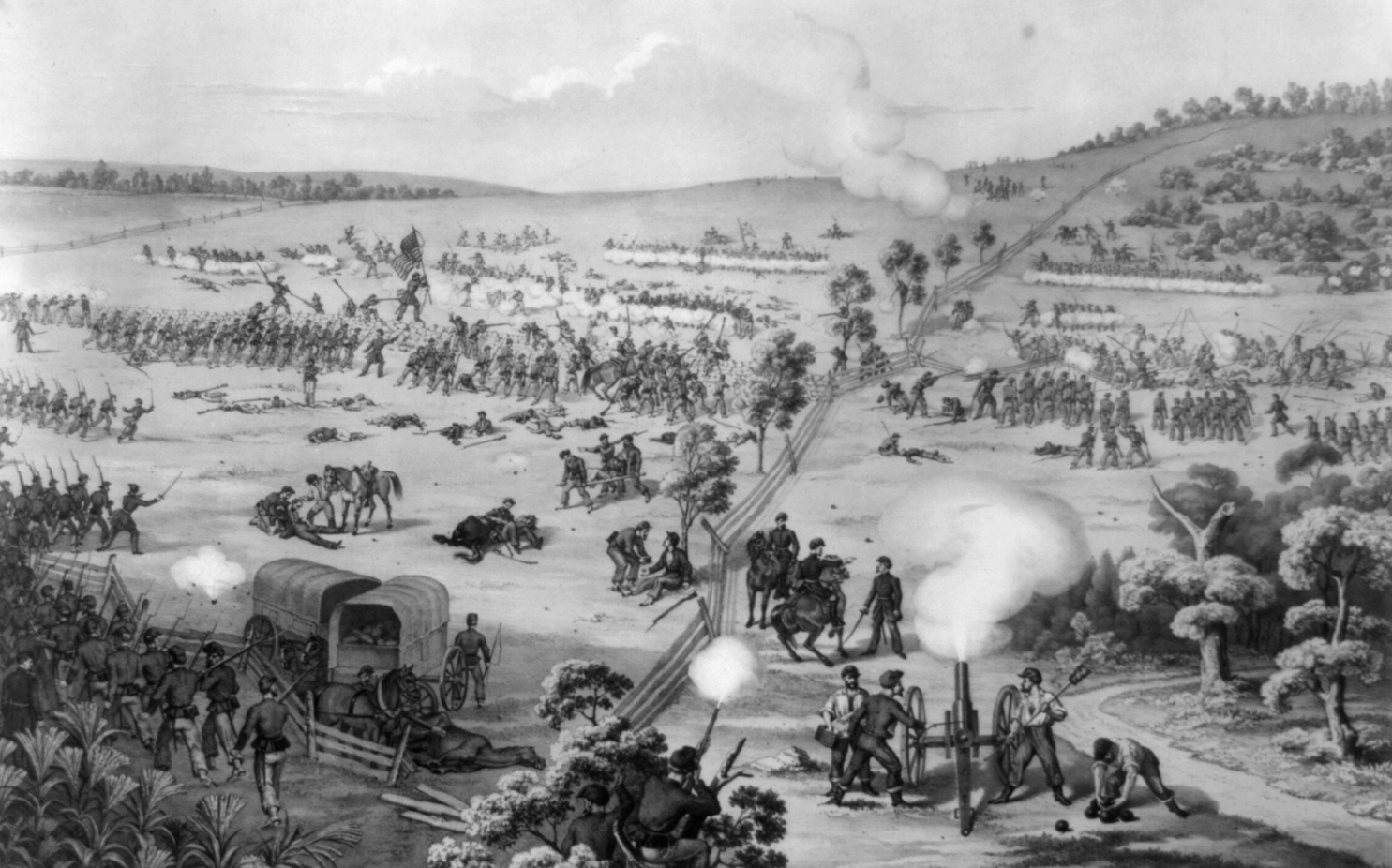

Major General McClellan, after receiving intelligence that General Robert E. Lee has split his force in two components, ordered the Ninth Corps to move on South Mountain and take control of Fox’s and Turner’s Gap. The 17th Regiment made its way toward Fox’s Gap to establish the front lines. Not intending to leave the gap without a fight, the Confederates cannonade the Union lines for hours. This is the first combat any of the Michiganders have experienced. Hunkered down in the fields and forest surrounding the mountain they call upon all their courage to stand fast in the face of death. Ordinary men, thrust suddenly into a terrible conflict they could not have imagined. But, there the 17th held, transfixed by their surroundings and the daunting task ahead of them. As the poem “At South Mountain” reads:

“The crack of the Minie rifle,

The shriek of the crashing shell,

The ring of the flashing sabre,

Their tale of the conflict tell,”[3]

As shot and shell raced overhead, the 17th waited, still uncertain of their fate but becoming quite sure of the danger that lay ahead. Any minute now they would be called upon to charge into the barrage. Then it would no longer matter where they came from, how they made their living back home, all that would matter is their inner strength to drive forward.

The Hour of Courage

At 4:00pm the wait was over; the order to charge was given and with a thunderous yell the 17th rose. Charging with such fury they blazed through the thick brush and trees to meet their foe. General Hooker describes the terrain as “precipitous, rugged, and wooded, and difficult of ascent to an infantry force, even in absence of a foe in front.”[4] The Confederates had taken up positions behind a stone wall at the top of the ridge. From here, a hailstorm of lead rained on the 17th, but it did little to slow the assault.

The poem describes the scene:

“Along the paths of the mountain

Moves up the dark-blue line,

The gun-wheels grind o’er the boulders,

The burnished bayonets shine.

Way up in the leafy covert

The curling smoke betrays

Where the foe throw down the gauntlet,”[3]

As the 17th crested the mountain they crashed into the Confederates, desperately trying to defend the stonewall, but the ferocity of the Michiganders proved too much to resist and the rebels fled down the mountain. Having devoured their first course of war the regiment gathers along the wall only having suffered minor casualties, readying themselves for an inevitable counterattack. They continue to retain control of Fox’s Gap for the remainder of the battle and continue with the Ninth Corps in the pursuit of General Lee’s forces. Completely untrained for war, they have distinguished themselves already as naturals, almost as good as regular soldiers, and just as eager.

The Stonewall Regiment

After such a successfully daring assault, the regiment did not go unnoticed. Earning the title “Stonewall Regiment”, the 17th never lost its vigor for war, playing vital roles in the Union’s quest to end the rebellion in the South and preserve the Union. Three days after the engagement at South Mountain, the regiment found themselves entangled in the bloodiest military conflict the United States has ever seen, Antietam. Fighting gallantly at Burnside’s Bridge the regiment miraculously emerged to capture the opposite heights, however, this time the cost was much heavier. Having experienced both the lucky and savage side of war the Stonewall Regiment carried themselves with distinction into every battle thereafter.

Major General Burnside even relied upon the regiment to provide a rear guard as the rest of the army withdrew to Knoxville, TN at the Battle of Campbell Station. There the regiment experienced tough fighting against Confederate General James Longstreet. By this point, the 17th was battle hardened and well versed in combat. They handled General Longstreet and allowed the Union armies to retreat to safety and slipped away in the night to aide in the repulsion of Confederate troops during the ensuing siege.

They continued to be an example of valor and courage for the rest of the Union armies throughout the war. 1863 saw five Medal of Honor recipients in the regiment. Lieutenant Colonel Frederic W. Smith, after losing an eye, rallied union troops at Lenoire Station, TN by picking up the American flag and leading a furious charge against the Confederates who seemed to have had the Union on its heels. Lt. Col. Smith was later captured in 1864 at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. In this battle three more Medal of Honor recipients emerged as they desperately tried to save the captured men. The rescue attempt was only semi-successful, but many men owe their lives to Private Frederick Alber, Sergeant Daniel McFall, and Sergeant Charles A. Thompson.

After the Union’s victory the regiment was mustered out of service within a few months. The men returned home to their previous occupations and their ordinary lives. These men remained undoubtedly changed by the war and by their own ability to muster such bravery within themselves. Even with this knowledge, they did not pursue a life of glory. But to their families and those across southern Michigan they returned as heroes who saved the Union from collapse.

Primary Sources

- Sneden, Robert Knox. “The Battle of South Mountain Md. Showing Positions at Fox’s and Turner’s Gaps, Sept. 14th 1862.” Library of Congress.

- “Battle of South Mountain, MD Fox’s and Turner’s Gap September 14, 1862 – 3:00 to 5:00 P.M.” Civil War Trust.

- “At South Mountain.” Harper’s Weekkly [New York City] 25 Oct. 1862: Harper’s Weekkly. Son of the South.

- Hooker, Joseph. “MGen Joseph Hooker’s Official Reports Reports of November 1862 on South Mountain and Antietam.” OFFICIAL RECORD 1st ser. 19.1 (1862): n. pag. Antietam on the Web. Brian Downey.

Secondary Sources

- Robertson, J. ,ed. (1882). Michigan in the War. Lansing WS George & Company.

- Record of service of Michigan volunteers in the Civil War, 1861-1865. 1900 Vol. 17. Ihling bros. & Everard.

- Clemens, T. G. Maryland Campaign. (2012, September 20). Encyclopedia Virginia.

- “Regimental Histories, Michigan“(2009, January 17). The Civil War Archives.