The Battle of Phillips Corners is proof of civil disunion that predates the Civil War. Where altercations of which have permanently changed the border lines of America’s maps as well as established the Upper Peninsula of Michigan’s existence.

The military affairs of America during the 1930s were suppressing Native American’s. During soon to be told altercations of Michigan and Ohio, the first Seminole War occurred and the Second Seminole War was underway, but the altercations would come to an end before the Mexican War.

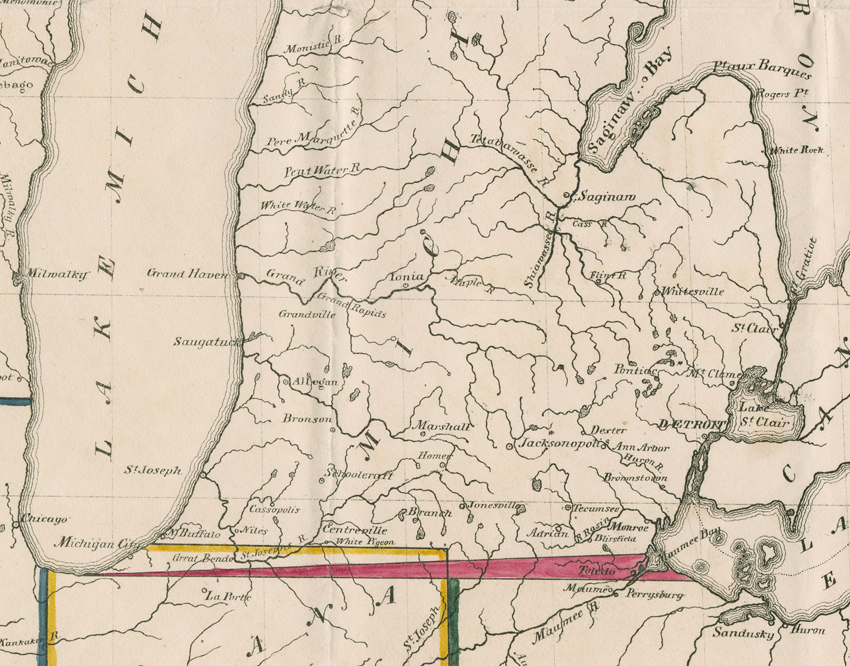

This was a time where the industrial revolution was soon to start, just before interchangeability of parts for weapons would begin to aid in the ease of production and replacements of parts for weapons. As well as before rifling gun barrels and using bullets over balls of lead created more accurate precision shooting riflemen which may have assisted in the Battle of Phillips Corners. During a time of Westward expansion, where poorly drawn maps and scrambling to claim territory and its resources, an altercation arose between Ohio and Michigan over a strip of land below the now border of the lower peninsula of Michigan, called the Toledo war. Due to the poorly drawn maps, Ohio had maps that showed their land ordinance lines going farther North than the maps that Michigan had shown the opposite. With the belief that Toledo would have been a major city as a gateway to the north and northwest both states fought over this strip of land. If the strip was given to Ohio it would give them access to a port on Erie Lake. Without the strip of land, Ohio would not own the port that connected to the Maumee River that would allow for flows of trade and canals. The claims to the possible ports and plans for canals also made the land desired by private interests. Thus, the land was in dispute by both Ohio and Michigan despite the Ordinance of 1787 that gave jurisdictional authority and claim over the land to Michigan. Therefore Ohio and Michigan sought resolution from Congress since the start of the 1800s, but due to the War of 1812 and the incompetence of Congress, the conflict lasted for over 30 years until the states decided to take matters into their own hands, despite this time period being known as the “30-year peace” spanning from 1815-1848.

During the Toledo War Michigan Governor Steven T. Mason had his men on high alert, with good reason. The governor of Ohio, Robert Lucas, sent a surveyor team to re-mark the boundary line for the 468 square mile strip that was eight miles wide. As recapped by a surveyor sent from Ohio when sent to remark the Harris Line (named after the man who marked it),

During our progress we had been constantly threatened by the authorities of Michigan, and spies from the territory, for the purpose of watching our movements and ascertaining our actual strength, were almost daily among us. On Saturday evening, the 25th ult., after having performed our very laborious day’s services, your commissioners, together with their party, retired to the distance of about one mile south of the line in Henry county, within the State of Ohio, where we thought to have rested quietly, and peaceably enjoy the blessing of the Sabbath, and especially not being engaged on the line, we thought ourselves secure for that day. [Seely: 413]

But while resting in that field, later to be known as Phillips Corners, the surveyors were found by Michigan men under the command of prison warden William McNair. His orders were to arrest or run off enemy Ohioan territorialists found in the area. The men were first approached by McNair and one other, but upon deciding to wait for the surveyors from the group to return, after questioning the men. McNair’s men did not show patience and approached the Ohioans from the trees they were watching from. Seeing the armed men, the Ohioans became nervous and reached for their weapons. It was here where the “battle” took place.

As recounted by the commissioners from Ohio the Michiganders fired with fifty-plus men as the Ohioans fled at the sight of them due to their superior numbers more so the superiority in firepower, as the Ohioans had five armed men escorting them. Not all of the Ohioans were able to retreat in time. Within the skirmish, only the Michiganders had fired at the Ohioans and received no return fire from them. Thus, no one was injured. The Michiganders succeeded in their mission to run off or capture those who attempted to remark the territorial line. As the Michiganders were able to capture nine of the Ohioan surveyors that could not get up in time. Containing among them (state militia) included two Captains, a Major, three Colonels, and four others arrested under violation of the Pains and Penalties Act, 1835. Which made it illegal for any attempt to extend Ohio’s control into the land in dispute. Later six of these men paid their bail to be released, two were determined not guilty, and one known as Feltcher was kept in custody for refusing to pay bail. The Battle of Phillips Corners had the commissioners recommending any additional work be done on the remarking of the Harris line, at least under such unbalanced conditions in terms of the rumored amount of numbers the Michiganders had, out of fear of bloodshed.

On the other hand as stated by the arresting official McNair, “Their published letters are calculated to give a false coloring to the transaction and misleading the public, I transmit a detailed statement from my own observation.” This now recounts the same battle as seen by the Michiganders point of view.

On Saturday afternoon, April 25, I received, as undersheriff, a warrant from Charles Hewitt, Esq., on the affidavit of Mr. Judson, a copy of which I forward. From the information I learned the commissioners had with them a guard of sharp-shooters for their protection, and that I could not serve the warrants without assistance. I therefore, ordered out a small posse from Tecumseh and a few from Adrian. That evening I mustered about thirty men in the village of Adrian, armed with muskets belonging to the territory of Michigan. One of our spies had stayed with the party the same night; from him I learned their number and location. Early the next morning I was on the march to meet Gov. Lucas’s “millions of freemen,” to arrest or drive them out of the wood, preferring the latter. [McNair: 24]

Already there are large differences from both letters. Where each side claims the other to have had superior numbers, as if to place themselves as David versus Goliath. McNair goes on to describe the confrontation. Claiming to have approached for arrest in a peaceful manner, McNair inquired for the commissioners who were not present. It was then that McNair’s men were seen, and the Ohioans soon reached for and loaded their weapons. After disarming one of the men himself and making his arrest the other eight men, who could not “leave the ground in time” as recounted by the Ohioan commissioners, Ohioans ran and fortified a nearby log house. McNair demanded their surrender, but after some time the action they took was to come, “out in single file with their rifles cocked and at the position of ready” [McNair: #] Then one of McNair’s men had caught tells of the Ohioans about to make a run for the woods in order to escape. As they soon did, the Michiganders fired over their head and charged to make arrests capturing the eight men. McNair rebuked the claim that their fire was close enough to actually endanger the men as claimed in the letter to Ohioan Governor Lucas. Insisting that if it were true he would have heard such claims from the prisoners and that those who had escaped only suffered from wet or lost clothing from crossing swamps on their way back to Perrysburg.

The actions described by McNair were backed by eyewitness accounts by J. W. Brown in a letter he wrote to acting governor Stevens T. Mason, the Governor of Michigan: “On the 26th of April, 1835, while attempting to remark Harris line within the territory. I was an eyewitness of most of the facts set forth by Col. William McNair, and know them to be true.”

Most of the conflicts and threats of bloodshed were just hype, as few injuries occurred in the whole Toledo war as compared to the promises of death from one side to the other. Such of the nature that the Battle of Phillips Corners truly displayed is better captured through the telling of Benjamin Baxter, one of the Tecumseh pioneers,

We, that is, some of the foot soldiers had not yet arrived on the spot but were rapidly approaching the forest. Every musket reverberated through the tall trees and sounded like a cannon. Stopping for a minute to consider how I could best find out which side I was on, I started for the battlefield, very excited…I think about twelve of the invaders were taken and about as many got away, running some 15 or 20 miles to Maumee, where they arrived in the night, very peculiarly and lightly clad, it is said, by reason of the prickly ash and blackberry bushes through which lay their line of retreat. Returning in triumph the next to Adrian the next day with our prisoners, it was concluded that by the proper authorities to retain only the engineer, Colonel Fletcher, in nominal imprisonment to test the validity of their arrest. The rest were then permitted to return to their homes in Ohio. [Baxter 16]

As a teenager, his boyish retelling of the tale gives a deeper understanding of how the atmosphere was when not put through the filters, of letters that would sway public opinion. On the other hand with public opinion the Michiganders thought the Ohioans to be timid people who could be scared off while the Ohioans thought the Michiganders to be ignorant that the decision would be based on politics and laws, not force or posturing. Governor Mason kept steadfast to his Pains and Penalties Act, but only due to Ohio governor Lucas’s refusals of offers to return any captured men that Lucas wished to request. Many back and forth of creating laws by each state that would punish the other for acts against them in the Toledo trip kept the two governors from being able to settle the dispute themselves, as President at the time Andrew Jackson wanted. Laws from Ohio that would punish Michiganders that followed the Pains and Penalties act, such as making it illegal to arrest Ohioans within the Toledo strip whereby their standards it would not be considered arrest in their eyes but “forced abduction”, as stated by governor Lucas. As things grew more intense in the court systems, the Michigan people readied for battle despite Jackson trying for peace.

The creation of Wisconsin also threatened claims of land for Michigan, President Andrew Jackson resolved the issue after much pressure on December 14th, 1837 in favor of Ohio to gain the Toledo strip, while Michigan was denied its statehood over the issue, causing them to relinquish the Toledo strip to Ohio. Under advisement by attorney general Benjamin F. Butler, Andrew Jackson believed the Toledo strip clearly belonged to Michigan but since Michigan was only a territory. Jackson had to weigh the importance of the electoral vote from Ohio. Ohio had already invested great amounts of money into canals, and their economy would depend greatly on the completion of them. Thereafter the settlement was made in favor of Ohio. This was met with hostility but in the end, although not appreciated at the time, in the settlement Michigan was granted the land that is now known as the Upper Peninsula, in addition to at last gaining statehood. The Toledo strip never became the major trade center it was believed it would become, and with the Upper Peninsula’s much greater amount of land, its large copper and iron resources, as well as vast timbers would prove to be a more than fair trade for Michigan.

Primary Source

- To his Excellency, Stevens T. Mason, Act. Gov. M. Territory. From J. W. Brown. “Michigan Historical Collections.” Google Books. Web. 11 Dec. 2015.

- To His Excellency, Stevens T. Mason. From WM. McNair, Undersheriff, Lenawee Co. Way, W. V. The Facts and Historical Events of the Toledo War of 1835 as Connected with the First Session of the Court of Common Pleas of Lucas County, Ohio. Toledo: Daily Commercial Steam Book and Job Printing House, 1869. Print.

- To Robert Lucas. From Jonathan Taylor, T. Patterson, Uri Seely} Commissioners. “Michigan Historical Collections.” Google Books. Web. 11 Dec. 2015.

- From Benjamin Baxter. Faber, Don (2008). The Toledo War The First Michigan-Ohio Rivalry. Ann Arbor.

Secondary Sources

- George, Marry (1971). The Rise and Fall of Toledo, Michigan……THE TOLEDO WAR!. Lansing.

- Faber, Don (2008). The Toledo War The First Michigan-Ohio Rivalry. Ann Arbor.

- Badenhop, Stephen W. (2008). “Federal Failures: The Ohio-Michigan Dispute“. Bowling Green.

- Grim, Joe (1987). “Michigan Voices Our State’s History in the Words of the People Who Lived It”. Detroit.