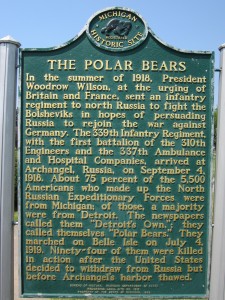

The United States had a late involvement in World War I, but few know that the U.S. had a small regiment of troops called Detroit’s Own Polar Bears deployed in northern Russia who remained in battle until 1919, even after the war had officially ended. These troops fought in negative 60 degree weather with communications and supplies strained, against an enemy they had no personal strife with. Their mission was to recover Allied supplies spread across the region and help the anti-Communist Czechoslovak Legion fight back against the communist uprisings, keeping Russia in the fight of WWI [11]. A monument was erected in Troy, Michigan as a tribute to the hard fought expedition into Northern Russia. The Polar Bears fought through bitter cold and harsh winter conditions unlike any of them had seen before, while fighting an enemy that felt that environment was normal. They held their ground and won most of their battles overall, maintaining their lines, although the future outcome of the fight looked bleak. This monument stands to honor those who perished for the war effort as well as those who survived, and provides a place of congregation in their memory.

Why We Went to Help Fight a Foreign Civil War

World War I was a war unlike any war prior. It involved countries from all over the world in a way that devastated almost all the parties involved, whether they “won” or not. New technologies and larger sized armies involved led to massive amounts of destruction as well as death. In mid-1917, the U.S. had joined the war effort with the Allied forces in order to defeat the Central Powers. By 1918, the Allies had a decent hold on victory over the Central Powers. Though an Armistice officially ending the war was signed on November 11, 1918, the Allies needed to fight with full force until that moment as not to let the Central Powers regain momentum against them. To help ensure the Allied victory, when one of the Allied nations had the threat of needing to withdraw from the war, the U.S. sent troops to accompany British units to Russia to help resolve their issues and stay in the War.

Prior to their involvement in WWI, Russia had been intertwined in various wars in the region. All of these where strenuous on the nation and they had lost almost all of them. The people of Russia were starving and the economy was faring poorly, leading people to lose faith in the current government. These issues along with the government’s commitment to WWI directly lead to the Russian revolution in 1917.

In 1914, Russia entered WWI with full force, but suffered major casualties and was militarily unsuited to fight the European powers. As the losses against the Central Powers kept stacking up, the people of Russia grew tired of fighting this war and dying with no advancement in sight. The communist Bolsheviks rose up and fought against the government promising to fix Russia of its problems [10]. A civil war ensued and as the Bolsheviks (the Reds) gained ground against the Mensheviks or White Russians (with support from the Czechoslovak Legion anti-Communist group), Russia expressed concern that they would not be able to remain in the Great War and deal with the civil war at the same time. Great Britain responded to this concern by sending troops to Russia’s northern front to help secure the region against the Reds.

In the summer of 1918, President Wilson agreed to the Allied pleas to help the effort in northern Russia, with the original intention of the U.S. troops never engaging in active fighting. One of the main goals was to help keep Russia in the war and thereby retain a two front war on Germany. This would be achieved by giving them the equipment and support they needed. The second goal was to protect the arms and supplies that the Allied powers had sent to Russia for their use in the Great War. The Bolsheviks were gaining control of the area and the Allies wanted to protect and retrieve the military supplies they stored in Archangel and Murmansk to keep them out of the Red’s hands.

Early Stages of the Expedition

In June 1918, 4,487 men, about 75% of whom were from Michigan and more specifically the Detroit area, were drafted for the war against Germany [11]. The American troops, known as “Detroit’s Own”, consisted of the 339th Infantry, 310th Engineers, 337th Field Hospital, and the 337th Ambulance Company. They were trained for a month at Camp Custer, Michigan and then shipped off to England where they were equipped and sent out into the war. Upon arriving, however, they were told that their destination had been changed. Their U.S. equipment was traded out with British grade winter gear and Russian Mosin-Nagant rifles. The change in gear was because they were now being sent to the bitter cold northern Russia and there was already a large supply of Russian rifles and ammunition there making the switch to Russian rifles economical and logistical but not desirable. The rifles were said to be very unreliable in that the ammunition jammed frequently and they were very inaccurate [11]. To add to the disappointment of being sent to the barren land of northern Russia and the removal of their U.S. equipment, they were also placed under British command. The British already had an expeditionary force there and were the main advocate for the U.S. involvement.

The troubles for the Polar Bears started before they even arrived at the battle front. Shortly after leaving the English port, an outbreak of Influenza ravaged the convoy killing over 100 soldiers [9]. Also, upon arriving in Archangel, they found that almost all of the military supplies that they had been sent to protect and retrieve had already been taken by the Reds [9]. The same case was found later when they made it up to Murmansk. The Expeditionary Force began to spread out over the region, trying to regain control. The White Russians did not have as strong of a holding as was originally thought and the Bolsheviks were gaining ground and overpowering them. This lead to some of the first fighting that the Polar Bears had to experience. President Wilson, in agreeing to send troops to northern Russia, had stated in a document which later became known as Wilson’s Aide-Memoire that “the only legitimate object for which American or allied troops can be employed, it submits, is to guard military stores which may subsequently be needed by Russian forces and to render such aid as may be acceptable to the Russians in the organization of their own self-defense” [7]. The British Major General Fredrick C. Poole was in command of the expedition and was thought to be unaware of Wilson’s restrictions on the use of U.S. troops. The Polar Bears were just supposed to be accompanying the other Allied forces and White Russians, providing self-defense and protection to the store houses. Instead, they were used to reclaim some of the land and directly confront the Bolsheviks.

Winter Campaigning and Worsening Conditions

The story of the Polar Bears is truly in the hardships of their situation. “The normal hardships of warfare were intensified by the deep snow, intense cold, darkness up in isolated detachments, winter in the Arctic Zone, and the long lines of communication, which were in constant danger of being cut by the enemy” [8]. While the engineers struggled to make camps that could keep the troops alive in the harsh winter but also be able to withstand artillery fire, the infantry struggled to fight in an environment that was unfamiliar to them. The winter in the Archangel region starts early even by Michigan standards. This meant that though they were given some winter supplies before they left England, they did not have enough for a full winter expedition. One of the big issues that the Polar Bears faced was the delay of supplies being delivered.

On November 17, their winter gear finally arrived to the troops dispersed throughout the region. Prior to the gear arriving from Archangel, it had been already snowing for six weeks. The problem of transportation would only get worse as the winter set in. As the temperatures dropped, the ports soon froze. This lead to the difficulty of getting supplies into Russia in the first place. The road and railroads were often times unmaintained and under Bolshevik control. Supply lines would have to be trenched through the snow and heavily guarded. The logistics problems soon came to hinder and deter the American troops. Even after the Armistice was signed, officially ending WWI, the soldiers could not be extracted due to their precarious positions in the wilderness and lack of easy transportation to withdraw from the area when the ports were frozen over. Some of the troops would have had to traverse thousands of miles in order to reach the port of Murmansk which remains ice-free year round [9]. Until better weather or the official, full-scale withdraw of the American troops happened, the Polar Bears would be mostly on their own during the winter campaign.

The weather and isolation played its obvious role in the Polar Bears’ hardships. It was often negative 60 degrees Fahrenheit with large amounts of snow fall. Being in the wilderness or inhabiting small towns, the 310th Engineers often needed to build blockhouses, barracks, and other living and defensive structures. This challenge was exacerbated when most of what was around was just raw materials and everything had to be built while exposed to the harsh cold and snow. The supplies that the troops did receive did not make the expedition much easier either. Most of what the Allied troops received came from Great Britain and the Americans felt that these items were sub-par and not adequate for their situation. The food rations were small and often not good and the equipment was not well suited for the cold weather. The soldiers often traded their British footwear with the locals or take new ones from the dead Bolsheviks [9].

The bitter cold tundra wasn’t the only factor that made waiting out the winter difficult for the Polar Bears. There was still fighting to do. Although the American troops were put on the defensive, having the intent of President Wilson’s orders sorted out, as well as the desire of waiting out the winter, the Bolsheviks decided to go on the offensive. Noticing the new strategy of the Polar Bears and their ever decreasing morale, the Reds saw it as an opportunity to conduct raids and ambushes on the disheartened troops. Colonel James A. Ruggles summarized the Polar Bears’ plight in the winter campaign:

The enemy greatly outnumbers us both in men and artillery; his morale, numbers, and efficiency have increased. We are more and more put upon the defensive, subjected to more and more frequent attacks and bombardment suffering many casualties. We have no reserves. Our men are often called upon to remain on duty for long periods without relief. There has been much criticism of the commanding officers, almost always British, and in some cases this has been amply justified. Owing to the increasing strength and morale of the enemy and his apparent intention to start a vigorous offensive later on, I am of the opinion that there is considerable danger that we shall be compelled to evacuate most of our advanced positions with grave losses both in men and supplies, [2].

The Bolsheviks had the advantage over the Allies in a winter campaign. The Reds knew the terrain far better and used their acclimation to the weather against the American soldiers. Being on the defensive, the goal of training and arming the White Russians to hold their own in the fight against the Reds was moved on once again. The problem was that the Czechs were losing support to their own cause and with the Bolsheviks gaining more ground across the country, the anti-communist sentiments shifted to give into the Reds. This flip-flop of allegiance also created a direct problem for the Allies because they didn’t know who was on what side. The White Russians that were still fighting with the Expeditionary Forces did do well and help out, but they required the leadership and presence of the Allies forces to remain in the fight [9]. Adding to the problems of retaining Russian support, when fighting the enemy, the troops didn’t know who was a Bolshevik soldier and who was just a civilian. They all dressed the same creating an issue that would be prevalent again in the Vietnam and later wars. This creates doubts in who they are fighting and can allow Bolshevik soldiers or spies to gain information on the Americans thinking that they are just the locals of the town the Allies were occupying.

The direct fighting was also a challenge. The Reds used their knowledge of the terrain to perform hit and run strikes that would avoid direct army on army fighting. There were often accounts of ambushes from the Reds on both traveling and stationary American regiments. Similar to the European campaign against Germany, trenches were used as a defensive position for the Polar Bears as well. The only difference was that the ones in northern Russia were built out of ice and snow compared to the ones in the dirt in Western Europe.

The Bolos advanced at us within striking distance… They were temporarily checked by the brave men of my platoon firing their rifles and machine guns against a force more than 100 time theirs… The town was now taking heavy rifle and artillery fire on three sides. The Bolos had sneaked in during the night and now raised up as one man out of the snow, wearing white camouflage smocks. Oh man, we hadn’t seen them! [6].

Bring Them Home!

The war in Europe was over when the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918. This was just three months after the Polar Bears were sent into Northern Russia and started spreading out over the region. In normal circumstances of war, this would mean that the fighting would stop and essentially all of the troops would be sent home. The problem was that the Russian war was a civil war and not directly related to WWI. This meant that when the armistice was signed, the Bolsheviks didn’t just stop fighting and thus the war wasn’t over for the Polar Bears. Once the troops found out that the war was over (and this wasn’t for about a month after it happened due to difficult communication lines), they wondered why they were still fighting and when they would be sent home. To them, though their mission was always slightly uncertain, it was for the good of the cause in WWI. When it was over they figured they would be sent home. This wasn’t the case, though, and wouldn’t be for another six months. As the situation worsened and the Americans’ morale dropped, they began to question their orders and goals. Though they did not disobey orders, they would question them more and perform them less heartedly, especially when they came from a British commander.

The American troops overseas longed to be home and had no desire to continue fighting in this foreign civil war. Their families back home also longed for the troops to be done fighting and come home. The home front was a large pull in the eventual withdraw of the Polar Bears. As the WWI veterans came home from Europe, they wondered when their family members would be coming back from Russia. As it became evident that they were not coming home at the same time, the families back home began to question the government and demand that their troops come home. As they received ill news, many had responses very similar to that of one fallen soldier’s loved one, “How could this be? We thought he’d be safe. How could this be? The war is over. The boys have come home. There not more dying. How can this be?” [3]. The Detroit’s Own Welfare Association in was formed in early 1919 and had thousands of members working to try and bring their Polar Bears home [13]. They staged protests and outreached to the troops’ families for support and government officials for action.

Starting in May 1919, the Polar Bears and their families got their wish and the extraction of American troops began. In June 1919, Archangel’s harbor thawed enough for a convoy of supply ships and a cruiser to get through and extract the whole of the American troops [9]. With the Americans gone, the British units only remained until the fall of 1919, leaving the White Russians to fend for themselves against the Reds. Early the following year, Archangel fell to the Bolsheviks and the capture of the city signified the victory of the communists in the Russian Civil War.

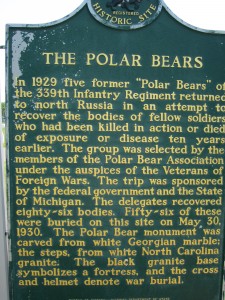

The American troops left in such a hurry, they left a lot of stuff behind. One of the big things left behind was about half of the 226 soldiers (not including the 100 that died from influenza) who lost their life in during the expedition and were buried throughout the countryside [4]. Before leaving on the convoy in June 1919, they gathered up as many of the bodies as they could but were not able to get them all since they were spread across the region. However, 114 troops were left buried in the Russian wilderness [4]. In 1929, five Polar Bear veterans returned to northern Russia to recover these lost remains. Financed by the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the state of Michigan, and the U.S. Army, they set out, mostly on horseback, to find their missing comrades using descriptions of locations from many of the surviving Polar Bears. When 86 of the bodies were recovered, they were loaded on a French cruiser to be brought back to the U.S. (Since the United States still didn’t have diplomatic relations with the new Russian government, an American ship arriving in port would cause conflict).

Dedication of the Monument and the Fallen Soldiers Returned Home

On May 30, 1930 a monument to the American Northern Russia Expeditionary Forces was dedicated to all of Detroit’s Own Polar Bears who served in the harsh environment too long after WWI officially ended. Of the 86 bodies recovered, 56 were buried around the Polar Bear monument. The Monument was carved from a single piece of white Georgia marble and the steps up to it are made from black North Carolina granite. The black granite base symbolizes a fortress and the cross and helmet denote war burial.

This monument is a tribute to the hard fought expedition into northern Russia and stands to honor those who did perish for the war effort and provide a place of congregation in their memory. Every year on Memorial Day, the Polar Bear Association with the help of White Chapel Memorial Cemetery hold a service to thank those troops who paid the ultimate price and as well as those who survived.

Primary Sources

- American Invaders Posing near the Corpse of the Murdered Bolshevik. Digital image. Encyclopedia of Safety. Surviving in the City, Surviving in the World. October 18, 2013.

- Colonel James A. Ruggles, 1919, Retrieved from [9].

- Family member of Sgt. Mick Kenney, most likely his sister. Approximately 1:40s:00 in documentary. Retrieved from [13].

- “Five Michigan Veterans Hunt Bodies of Buddies.” The Tuscaloosa News, 10 September 1929, page six.

- Reburial Ceremony and Dedication of the Polar Bear Monument, May 30, 1930. Digital Image. Polar Bear Memorial Association.

- The diary entry of Lt. Harry Mead, Co A, 339th Infantry. Entry Date: January 19, 1919. At 1:14:24 in documentary. Retrieved from [8].

- United States of America. Department of State. Aide-Memoire, July 17 1918. By Woodrow Wilson. President Wilson’s Aide-Memoire on the Subject of Military Intervention in Russia. George Kennan, Princeton University, 1958. 30 Oct. 2016.

Secondary Sources

- American Polar Bears: The American Expeditionary Force to Northern Russia. Doughboy Center: The Story of the American Expeditionary Forces. 2000.

- Barnnes, Alexander and Rhodes, Cassandra . “The Polar Bear Expedition: The U.S. Intervention in Northern Russia, 1918-1919”. Army Sustainment. Pg. 52-57. March 2012.

- Meissner, Daniel J. “The Russian Revolution of 1917.” The Russian Revolution of 1917. History Department at Marquette University, n.d.

- Rhodes, Benjamin. “The Anglo-American Intervention at Archangel, 1918-1919: The Role of the 339th Infantry”. The International History Review, Vol 8, No 3, pg. 367-388. August 1986.

- Smith, Gordon. North Russia, Murmansk to Divina River. Digital image. Naval History.

- Voices of a Never Ending Dawn. Directed by Pamela Peak, produced by Pamela Peak and Larry Chase, 2009.

For Further Reading

- “Polar Bear Expedition.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d.

- “The Polar Bears.” Michigan Historical Markers. State of Michigan, 1988.

- Moore, Joel R., Harry H. Mead, and Lewis E. Jahns. The History of the American Expedition Fighting the Bolsheviki Campaigning in North Russia 1918-1919. Don Kostuch, 2007.