The United States’ victory in World War II can be attributed to any number of strategic, tactical and technological developments, though it has often been observed that the United States’ industrial might significantly influenced the War’s eventual outcome. This “industrial might” directly relied on the ability to move iron ore from the western Lake Superior region to steel mills in the southern and eastern Great Lakes. All ore was shipped via freighter and the overwhelming majority of iron ore used to fuel the war effort passed through one vulnerable choke point, the destruction of which could bring the production of all steel-related industries to a halt. This choke point is the Soo Locks in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and this is its story.

Background

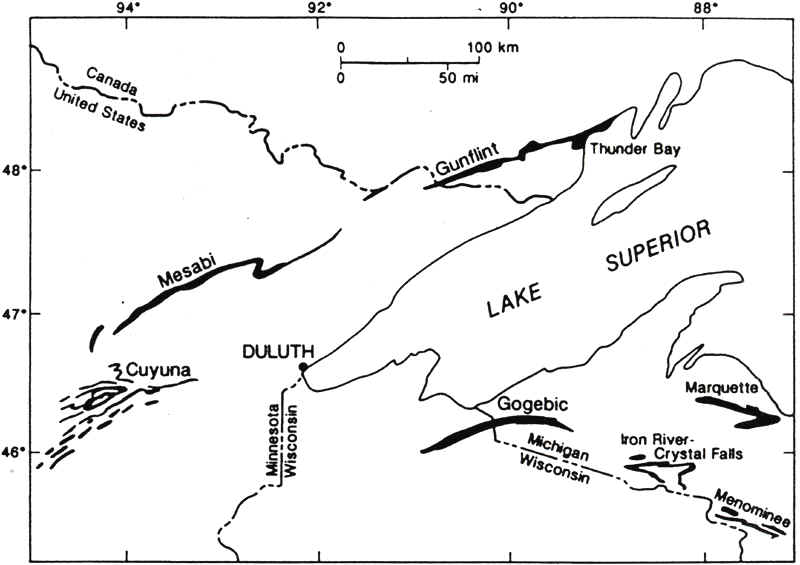

The bulk of the nation’s military machine was fueled by steel produced in the mills of Gary, Lake Erie, The Mahoning Valley of Ohio and Pittsburgh (The Might of America), but what were these mills fueled by? Steel is produced by melting and mixing iron ore with carbon to remove impurities and to create a stronger iron alloy, i.e. steel (How Steel is Made). The iron ore used in this process (of which steel is generally over 90% iron) is and was mined in specific regions of northern Minnesota and in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

Due to the nature of iron ore (its density and the sheer volume of it regularly produced), transportation by ship was the primary method of moving the ore to the mills. Ships could move this material cheaper and more efficiently than trains, and because of the location of the mines, nearly 90% of the domestic ore produced was shipped on Lake Superior, through the Soo Locks and into the lower Great Lakes (North). It is no surprise that because of this J. Edgar Hoover called Great Lakes iron ore shipping the “jugular vein” of the war production effort. (Kakela) Additionally, over 1 billion bushels of wheat and 250 million bushels of other grain from the Dakotas, 30 million barrels of flour and 100 million feet of lumber flowed through this same route. The average tonnage passed through the locks exceeded that which passed through the Panama Canal by five times (The Might of America).

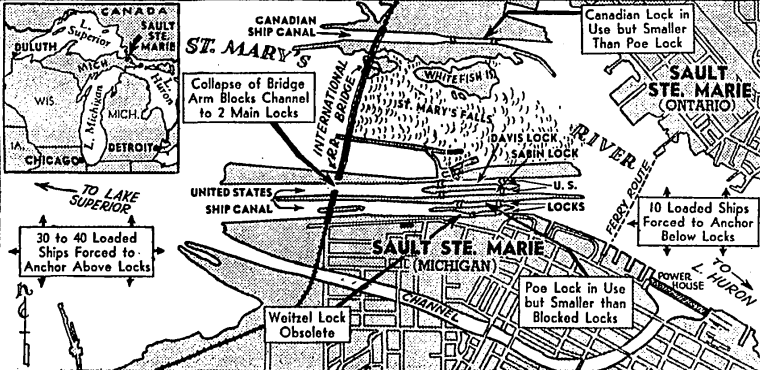

At the start of the war, the Soo Locks consisted of five locks in total. The Canadians controlled their own lock north of the St. Mary’s Falls and the international border while the United States operated four locks between the border and Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. These locks consisted of the Davis and Sabin Locks (both of which allowed for ship drafts up to 20 ft (Arbic)), the Poe Lock (which allowed for up to 16.5 ft drafts (Wrecked Bridge Blocks Soo)) and the then obsolete Weitzel Lock.

Pre-War

At the time of the British declaration of war against the Germans, it became clear to Canada (a member of the British Commonwealth) that they would become involved in the war. Recognizing the role the locks played in their industry, the Canadian government was the first to garrison their lock facilities (Stevens). Though still trying to maintain a stance of neutrality, the United States quietly began to fortify their locks as well. The nearby Fort Brady already housed 4 companies of the 2nd Infantry division and these troops began to patrol the grounds of the locks and guarded all passenger vessels traversing the facilities. Machine gun nests and search lights were installed overlooking the locks and armed US Coast Guard patrols began at both ends of the locks starting September 7, 1939 (Conn, et. al.).

Troops were later reduced to one company when it was realized that the number of men stationed exceed the number needed for guard duty. In the Fall of 1940 however, the Federal Bureau of Investigation called for a re-examination of the Army’s Sault defenses. The Permanent Joint Board on Defense proposed that the United States and Canada work in conjunction to better guard the Sault and to “establish a central authority over the local defenses” (Conn et. al.). Per request, President Franklin Roosevelt issued an executive order which created the Military District of Sault Ste. Marie on March 15, 1941 (Stevens). According to a news bulletin published in the March 24, 1943 Chicago Tribune:

By its proclamation the army takes over control of civilian defense in the area, assumes the power to expel any residents deemed dangerous to the war effort and sets up closer supervision of all civilians entering.

Soon after this order, Col. Fred Cruse (the man previously charged with the protection of the Panama Canal) was selected to command the newly created military district (Arbic). He expediently met with his Canadian counterpart and thus began the relationship of close cooperation between the two countries in defense of the Sault. Because of the “guard” nature of the job, the remaining company of 2nd Infantry was replaced with Military Police of the 702nd Battalion (Conn et. al.).

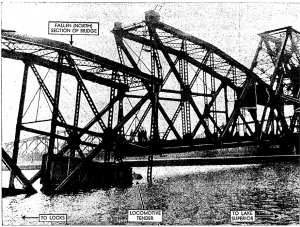

On October 7, 1941, an event would transpire that would fully illustrate the vulnerability of the Soo Locks against even a minor attack. Early that morning, a train bridge crossing the locks collapsed into the channel feeding the deeper Davis and Sabin Locks, blocking them off from traffic and dumping the locomotive it carried into the canal while killing two railway employees (Wrecked Bridge Blocks Soo). As most freighters had drafts greater than the smaller Poe Lock would allow, they were forced to anchor and await the clearing of the obstruction. The train and collapsed bridge was finally removed after 48 hours, at which time 50 anchored freighters had been delayed by the incident. Though sabotage was quickly ruled out by Cruse, the two-day shipping interruption showed how a much larger incident, which could have actually harmed the lock itself, could have set back freighters by weeks or months. This type of setback would be totally unacceptable, since mills such as those in Cleveland only had enough ore stockpiled to last six weeks (Arbic). Furthermore, if such an incident occurred within the 8 month shipping window in which the lakes weren’t frozen, an entire year’s worth of Lake Superior iron ore could feasibly be lost to the inability to traverse the Soo Locks.

The War Begins

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Hawaii and the United States soon found itself engaged in wars in both the Pacific and Europe. In the following months, the War Department ordered a reevaluation of the Lock’s defenses. The Permanent Joint Board on Defense recommended significantly increasing the defenses surrounding the locks. The reasons behind such precautions stemmed from fears presented in Guarding the United States and Its Outposts:

[T]he Germans might send submarines or surface ships into Hudson Bay and from its nearest arm – four hundred miles away – launch a bombing attack, or they might fly long-range bombers all the way from Norway along the Great Circle route, or they might attempt a parachute attack from planes flown from Norway, the paratroops carrying out sabotage after they landed.

Though the Army agreed that it was unlikely, the occurrence of such attacks were “at least possible” (Conn, et. al.). In the event that the Sault’s eventual fortifications proved to be insufficient, a new railroad was built from Marquette to Escanaba, MI to facilitate partial transportation of iron ore to Lake Michigan freighters (WPB Tells).

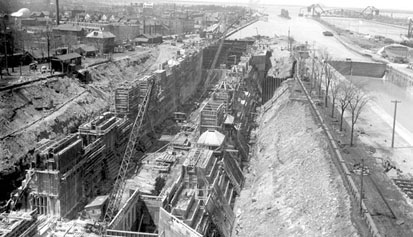

With the declaration of war on two fronts came the need to significantly increase the production of war products and materials, and therefore, iron ore. The production of iron ore was limited only by how quickly it could be shipped out, making the number of ships and locks in the Sault the two principle bottlenecks of the steel industry. To increase the shipping capacity of the Soo Locks, plans were made and passed by Congress in March, 1942 to replace the existing and obsolete Weitzel lock with a significantly larger and deeper lock. This lock, which was to be 30 ft deep, allowed ships to traverse the lock which would not otherwise fit through the Davis and Sabin Locks, and thus allowed for higher tonnages of material per lock cycle, all while replacing a commercially unutilized lock in the process (Arbic & Steinhaus).

To additionally increase shipping capacity, the War Production Board asked the maritime commission to convert 17 automobile transportation ships to ore carriers, while also building new boats and appealing to the Bureau of Navigation to lift load restrictions already in place on ships in the Great Lakes (Need of Ore Ships Urgent).

While plans to build the new lock were underway, the military began moving more troops and equipment to defend the locks from potential attackers. Among the first to arrive were the 131st Infantry, 100th Coast Artillery (AA) and 39th Barrage Balloon Battalion. A chemical unit with smoke screen machines would later join them. Within a month, 7,000 officers and men were stationed in Sault Ste. Marie, with approximately 900 of those stationed on the Canadian side of the city (Arbic). The troops stationed there were specialized for various duties, namely the infantry being responsible for combating enemy paratroopers, the artillery being responsible for anti-aircraft operations and the balloon battalion in charge of controlling the hydrogen filled barrage balloons.

Though the purpose of “anti-aircraft” and “combating enemy paratroopers” can be easily understood, one of the more unusual activities in the Sault at this time was the use of the aforementioned barrage balloons. These balloons were very large and filled with hydrogen gas. They were tethered to the ground with long steel cable of up to 2,000 ft (Arbic) and were positioned in such a way that any enemy aircraft attempting to torpedo bomb the locks would get tangled in the balloons’ cables and crash before reaching their target. They were also frequently swept away or destroyed during bad weather.

Though many details of the Soo Locks’ defenses were kept from the public, a post VE-Day article in the Chicago Tribune on August 17, 1945 described that at the height of the Sault’s security, 12,000 soldiers and officers were present within the military district along with “51 barrage balloons floated over the locks [and] 48 anti-aircraft guns poked from tennis courts, parks and back yards”, making Sault Ste. Marie “the most heavily guarded inland city in the United States.” Though several articles of the time state that the of soldiers protecting the Sault numbered 12,000, official military documents cited within Guarding the United States and Its Outposts maintain this number to be no higher than 7,300 troops.

Regardless of this disparity in data, the sudden influx of soldiers, officers and workers constructing the new lock led to a severe housing crisis. Before new quarters could be built, soldiers were initially housed in the Sault’s Christopher Columbus and American Legion Halls, the Union Carbide Recreation Building, and the gymnasiums of local schools (Arbic & Steinhaus). Twenty housing buildings were quickly erected around Fort Brady to house the additional troops, with the Army constructing a new hospital and the Canadians building quarters for up to 2,000 men. Additionally, the Sault Ste. Marie chamber of commerce reportedly encouraged local residents to rent rooms in their homes to both soldiers and lock workers (Arbic).

In May 1942, the Canadian government organized a “ground observer aircraft warning system” which consisted of 266 posts that were manned 24 hours a day (Conn, et. al.). These posts were spread throughout Ontario between Hudson Bay and Sault Ste. Marie. The Canadians also allowed for the installation of 5 radar stations manned by US troops in northern Ontario to further enhance the early warning systems. Additional measures taken to protect the locks took the form of wire mesh nets inside the locks to catch torpedo bombs (Edwards), three new high ground gun emplacements (Arbic) and the construction of two new emergency airfields near Kinross and Raco, MI (Stevens).

Drawdown

By the end of 1942, the Operations Division of the War Department recognized that the currently stationed 7,300 troops was excessive. With the new lock nearing completion, it was only a matter of time until the forces would be drastically reduced. The new lock was completed and opened for operation on July 11, 1943, seven months ahead of schedule (Soo Lock Named). Significantly more iron ore could now be passed through the Soo Locks than ever before. Due to a need for more trained soldiers on overseas duty and the provision of spare locks parts (Conn et. al.), the military was confident that even in the extremely unlikely event of a successful attack by the Germans, the locks could be repaired quickly and shipping would no longer be significantly delayed (Stevens).

By the first of September 1943, total troops stationed at the Sault were reduced to 2,500, per orders of the War Department. That winter all radar stations and observation posts were vacated, along with the removal of all anti-aircraft guns and equipment. By Januray 1944, only a single battalion of military police remained (Conn, et. al.). In October 1945, four months after the end of the war in Europe, Fort Brady was closed indefinitely (Arbic & Steinhaus).

Legacy

It is estimated that iron ore in excess of 300 million tons passed through the Soo Locks over the course of the war (The Might Of America), allowing for the creation of over 380 million tons of steel over the same time period (Statistical Summary). Nearly every object used in the war was made of this steel, from battleships and aircraft carriers, to tanks and artillery, down to soldier’s individual guns and helmets. From this point of view it is easily seen just how important the Soo Locks were to the United States’ war effort, and how differently the war would have ended had the iron ore stopped flowing.

Primary Sources:

1. Conn, Stetson. Engelman, Rose C.. Fairchild, Byron. “Guarding the United States and Its Outposts”. Center of Military History , United States Army. Washington DC, 2000. pp. 102-105.

2. “Need of Ore Ships Urgent, WPB Reports”. Chicago Daily Tribune. 21 February, 1942. p. 21.

3. “WPB Tells How Vital Industry Was Guarded”. Chicago Daily Tribune. 16 September, 1945. p. 12.

4. “Soo Lock Named For M’Arthur To Open Today”. Chicago Daily Tribune. 11 July, 1943. p. 20.

5. “Secrecy Lifted On Hidden Guns At Soo Canal”. Chicago Daily Tribune. 17 August, 1945. p. 15.

6. “The Might Of America”. Chicago Daily Tribune. 18 August, 1945. p. 10.

7. “Wrecked Bridge Blocks Soo; Big Ore Ships Halt”. Chicago Daily Tribune. 8 October, 1941. p. 3.

8. “Army Tightens Control of Soo Locks Defenses”. Chicago Daily Tribune. 24 March, 1943. p. 8.

Secondary Sources:

9. Arbic, Bernie. City of Rapids: Sault Ste. Marie’s Heritage. The Prescilla Press. Allegan Forest, MI, 2003.

10. Arbic, Bernie. Steinhaus, Nancy. Upbound Downbound: The Story of the Soo Locks. The Prescilla Press. Allegan Forest, MI, 2005.

12. “How Steel is Made: A Brief Summary of a Blast Furnace”. Keen Ovens, Henkel Enterprises, LLC.

15. “Soo Locks History”. US Army Corps of Engineers, Detriot District.

16. Statistical Summary 1941-1947: The Mineral Industry of the British Commonwealth and Foreign Countries. Her Majesty’s Stationary Office. London, 1949.

17. Stevens, Deidre. “When World War II Came to the Sault.” HSMichigan.org. April 2012.

For Further Reading:

– June, Mary M. “Timeline and History for Sault Ste. Marie”. City of Sault Ste. Marie. March 7, 2000.

– “History of Sault Ste. Marie in Photographs”. ilovethesoo. 2012.