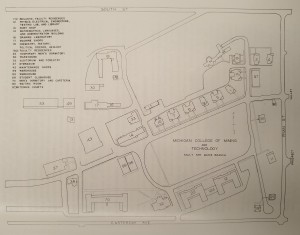

![Sault Ste Marie branch of Michigan College of Mining Technology, formerly [New] Fort Brady.](http://ss.sites.mtu.edu/mhugl/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Aerial-MCM-300x244.jpg)

History of Fort Brady

In 1822, Fort Brady was built seven miles west of Sault Ste Marie on the coast of Lake Superior. Due to size constraints, Fort Brady was rebuilt on a hilltop overlooking the St. Mary River in Sault Ste Marie in 1893. It was suitably nicknamed “New” Fort Brady, and was built to be much larger than its original due to the growing use of the Soo Locks [5]. Luckily for the Army, this rebuilding of a now-vital fort took place just in time to train a great number of troops for the Spanish-American War [4].

In 1913, there was talk of closing Fort Brady, but World War I developed a year later, and all talk of closing the fort subsided. The number of soldiers stationed at this fort increased for training purposes, and the Michigan National Guard took the role of guarding an important shipping route at this fort. The fort’s population shrunk following the war, and rose once more preceding World War II [4].

Fort Brady became a popular destination for many troops, especially during World War II, due to its strategic location, variety of terrain, and its changing weather conditions [4]. All of these factors combined provided for some of the best soldier training in the United States. During this war, the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd Infantry, the 702nd Military Police Battalion, and the 131st Infantry Battalion all cycled through this fort for training, in that order. They trained for fighting in a narrow body of water, winter maneuvers, and even “the art of soldiering on skis” and snowshoes, respectively [4]. Eventually, an aviation school was established at the fort, again due to its strategic location and its wide variation of weather conditions, and the 100th Coast Artillery arrived for training [4].

At this point, Fort Brady was becoming overcrowded, and the military planners had not anticipated such a large residency when rebuilding the fort. Building more barracks was not a viable solution at this point, since there were still too few facilities to accommodate the vast amount of soldiers at this fort. The fort struggled to maintain its soldiers throughout WWII as the size limitations of Fort Brady were pushed to its limits, and the Army decided to classify Fort Brady as surplus after the war [4].

Fort Brady was a huge part of Sault Ste Marie; in fact, the community essentially revolved around it. The soldiers helped grow the economy and the size of the city. When news of the Army abandoning the fort got around to the public, there was a large outcry against this, as this would have decimated the prosperity of the Sault and surrounding area. However, this did not stop the Army from leaving. Fort Brady was left in the hands of caretakers. Sadly, over time, now abandoned Fort Brady became dilapidated. Eventually, the caretakers started to tear down the fort, starting with the buildings that were in the most unstable conditions [6].

As the citizens of Sault Ste Marie caught on to this, they started to take action. A group of citizens obtained the fort from the Army to change it into educational facility, as this seemed to be a popular next step for the fort by the surrounding citizens [6]. News of this desired action for the abandoned fort reached higher up in government, and fairly quickly, demolition ceased [6].

Acquisition and Renovation of Fort Brady

At the same time at the opposite end of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Michigan Tech’s president, Dr. Grover C. Dillman, was experiencing enrollment issues, but in a positive way [6]. When World War II ended, a GI Bill was created in order to provide veterans with benefits, including financial assistance with attending a college or university. The Michigan College of Mining and Technology campus in Houghton was too small to allow such a large number of soldiers returning from war to attend school on the campus in Houghton [6]. At the end of 1945 when Dr. Dillman found about the desire to convert an old Army fort into a college, he took the offer up immediately [6].

In order for the Sault branch to be successful, Dillman needed to appoint someone with great leadership to help prepare the Sault branch for the fall semester. For a campus that was designed to catch the overflow of World War II veterans, no one would be better to establish it than a retired officer. Professor H. W. Risteen was a retired navy captain with a great deal of leadership experience, and Dr. Dillman knew he could trust him to find the right faculty to instruct the students of this branch [6]. Dillman appointed him to full professor of the Sault branch of Michigan Tech [6].

As reconstruction of the retired fort ensued, Dillman ran into issues from the government regarding acquisition of the fort. At this time, the government had deemed many forts as surplus due to the downsizing of the armed forces following WWII, and was selling many of these forts all at once. In order to better keep track of all of these sales, the government slowed down the sales process. However, the Sault branch of Michigan Tech was able to overcome this setback and the school was functional enough in time for registration, also known as Busy Week, starting Monday, November 1, 1946 [2]. School officially started Friday, November 5, 1946 and was fully operational by December of 1946 [6, 7].

Development of the Sault Branch of MCMT

The Sault Ste. Marie branch of the Michigan College of Mining and Technology (MCMT) served to contain the growing student population of the Houghton campus. Due to the college’s placement on the former military base, this branch specialized in recruiting World War II veterans who wanted to come back to school after serving. In 1946, between both branches, the Michigan College of Mining and Technology had 2,000 students [7]. Of those students, the Sault Ste. Marie branch had an enrollment of 260 students at the beginning of the year [7].

Of these 260 students, 215 of these students were engineering students and fourteen of them studied liberal arts. Despite such a small number of them, the school planned to expand the liberal arts program for the up and coming years. In this incoming class, 92 students were not veterans, 167 were veterans, and only one student was female [the Sault Evening News did not specify whether she was a veteran] [2].

Upon the opening of the Sault branch of the Michigan College of Mining and Technology, only three of the 64 buildings from Fort Brady were used for all of the offices and classrooms [4]. Just like the soldiers that lived on the Army base once before, the students lived in the barracks, and these living quarters had hardly been renovated to better suit the first freshman class. To accommodate this inconvenience, the school provided study rooms, locker rooms, lounge rooms, and bathrooms for the students to use in a separate location. The school was working quickly to renovate another barrack building at a different location on the campus into several dormitories with double rooms. The library and the gymnasium were kept untouched, as they already suited the student’s needs [2].

The Sault Ste. Marie branch of the Michigan College of Mining and Technology quickly became a strong entity of the school’s network, as its student population grew rapidly. In the beginning of 1955, the Mining College asked for approval from the Board of Control to make the Sault Ste. Marie branch a permanent part of the college [7]. This vote passed, and in June of that year, the Sault Ste. Marie branch became an official part of the Michigan College of Mining and Technology [7].

The Sault Ste. Marie branch first acted as a one-year transfer school. This may have been to allow first year students to drop out due to the school’s rigorous academic course load. However, by 1956, with the growing success of the Sault Ste. Marie branch, the school expanded and became a two-year transfer school to the Houghton branch and a community college which focused on non-technical associate’s degrees [7].

The addition of the community college option led many to question the mission of Michigan College of Mining and Technology, despite the school’s glaringly specific name. There was talk of gearing this school toward a liberal arts college, to accommodate the students who used the school as a two-year community college [7]. In 1958, the school decided to maintain its image as the Mining College and looked into developing the school into a four year technical program [7]. At the time, the Sault branch’s enrollment was just over 400, and needed 700 students to achieve this [7]. The school really focused on recruitment to achieve this goal. By 1960, the school increased its enrollment almost 20% to roughly 470 students [7]. While this was still not enough to allow the school to host a four-year technical program, the Sault branch extended its associate’s program to its technical degrees in 1962, and by 1964, the school rolled out a baccalaureate program which offered degrees in business administration, biological sciences, and medical technology [7].

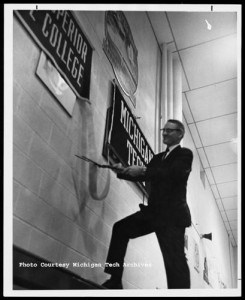

At this point, it was clear to see that as the Michigan College of Mining and Technology, or Michigan Tech, grew in size, it was moving away from its original focus on engineering and mining. This not only occurred at the Sault branch, but also at the main Houghton campus as well. To allow the school to better represent itself, the president of the school changed its name to what it’s known as today: Michigan Technological University [8]. This name was chosen to reflect the nickname (Michigan Tech) that the school had used for quite some time, and to show that it had grown from a college to a university [8]. The change became effective on January 1, 1964 [3].

However, the Board of Control of the Sault branch favored expansion, and wanted to establish four-year programs for all of its areas of study. The Sault branch of Michigan Tech was ready for autonomy [7]. In June 1966, the Board of Control of both university sites met and agreed that severance was the best course of action to take [7]. This would allow the Sault branch to focus more on its liberal arts programs and less on engineering, which is what was favored by the students [7]. However, the Sault branch was not entirely autonomous. It was renamed to Lake Superior State College (LSSC). Each school’s operations were separate, but LSSC still drew some funds from Michigan Tech [7]. Otherwise, these two schools acted totally independently of each other. This is how a one fort extended its influence from the Army to the Michigan Tech community and left a remarkable impression on the Upper Peninsula.

Primary Sources

- Michigan College of Mining and Technology (1947). Course Catalog. Bulletin of the Michigan College of Mining and Technology. 20.2.

- “Sault Becomes a College Town Monday.” The Evening News [Sault Ste. Marie] 26 Oct. 1946, 47th ed., sec. 62: 1-8.

- “By Action of the Legislature of Michigan, MICHIGAN COLLEGE OF MINING AND TECHNOLOGY …,” 1963. Copper Country Vertical File: Sault Ste. Marie Branch. Michigan Tech Archives & Copper Country Historical Collections.

Secondary Sources

- Stanley, Charlene Jeanne. “Fort Brady During World War II.” Diss. Northern Michigan University, 1983.

- Lake Superior State University. Fort Brady.

- Michigan Technological University (1987). “1946-1986 The First Forty Years,” The History of Michigan Tech-Sault Branch and Lake Superior State College. 186-188.

- Michigan Technological University (1985). “Michigan Tech Sault Ste. Marie Branch,” Michigan Tech Centennial 1885-1985. Chelsea, MI. 193-199.

- “A History.” MTU History. Michigan Technological University, published after 1991.

For Further Reading

- Wikipedia. Fort Brady.

- Wikipedia. Michigan Technological University.

- MHUGL. Lockdown: The Story of the Soo Locks and WWII

For Further Reading

- Wikipedia. Fort Brady.

- Wikipedia. Michigan Technological University.

- MHUGL. Lockdown: The Story of the Soo Locks and WWII

- MHUGL. Sault Sainte Marie, MI: The Soo Locks in WWII