Pontiac’s Siege of Detroit was the flashpoint that began what is now commonly referred to as “Pontiac’s Rebellion”. Discontented with the actions of the British in the region, the Native Americans unified themselves and besieged several forts in the Great Lakes Region. Although ultimately unsuccessful, the Siege of Fort Detroit, and Pontiac’s Rebellion in general, lead to reforms in British policy that positively affected the peoples of the region momentarily, and helped lead to the American Revolution.

Sewing Discontent

The events leading up to the war, include the French and Indian wars (known in Europe as the Seven Years’ War) fought in the Americas in the 1750’s. The Native Americans, whom sided with both sides, depending on the tribe, primarily decided to fight on the side of the French, which caused spite among both the colonists and the British[5]. British policies towards the Indigenous peoples would be vastly different from that of the French. Instead of cultivating friendship and trade, the British decided that it would be better to treat them as though they were a conquered peoples[6]. This was mainly done under the command of British General Jeffery Amherst.

General Jeffery Amherst became the person in charge of the Great Lakes Territories after his success in capturing Montreal in the French-and-Indian Wars[7], essentially ending France’s control of the Great Lakes Region. For this accomplishment, he was promoted to the rank of Major General on the 11/29/1760, and knighted as a “knight of the order of the bath” on 8/11/1761 [8].

General Jeffery Amherst had a special contempt for the Native Americans. He exploited them economically, and limited their access to vital resources such as gunpowder and ammunition. His contempt was so great that he even considered, although it is debated whether or not it was actually executed, a primitive form of biological warfare; infected blankets containing the smallpox virus that could be given to the Native Americans to wipe them out en masse[1,2].

Over the years that General Amherst controlled the Great Lakes Territory, the Native Americans began to put their differences amongst one another aside; instead forming a sort of coalition to oppose British rule in the era. This war would begin in several locations in the Great Lakes at once; And Fort Detroit was one of the first places attacked by the Native Americans

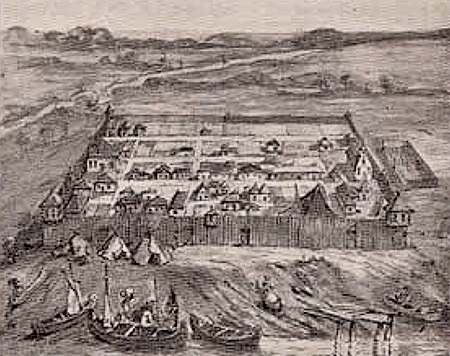

The Siege on Fort Detroit

Pontiac was unable to rapidly convince the other various tribes to turn against the British. The process took a few years, eventually culminating in an alliance of various factions of Ottawa, Huron, and Potawatomis tribes to join him, but many other tribes at least remained partially loyal to the English Crown. This would be a major deciding factor in how the Battle of Fort Detroit would ultimately fail, and become a siege of the fort instead. Those whom had not allied with Pontiac had alerted the English of his brewing plans; and the English began to prepare accordingly. When Pontiac rallied his coalition in late April 1763, opponents of the plan informed the British of the impending attack, which was to prove instrumental in the course of the encounter.

In early May, Pontiac, a leader of a local Ottawa Chief and military leader, gathered together the various tribes in order to stage an assault on the fort. As a result of other tribal leader informing the English, when Pontiac and several hundred Indians attempted to enter the fort with weapons, in order to conquer and destroy it, they were met with an armed garrison of several hundred Englishmen. Upon seeing this, Pontiac and his forces withdrew and began to lay siege to the Fort; while also capturing various people on the outskirts of the town. John Rutherfurd, an Englishman who was captured and later released by the Native Americans is said to have witnessed the cannibalization of at least one captured person, as detailed in his writings about the siege afterwards [3].

Several shipments of supplies to the fort sent by the British to aid the fort throughout the siege were attacked and seized by the Native Americans, the first of which was lead by Lieutenant Abraham Cuyler. Cuyler, whom had not been informed of the ongoing siege, had made camp a short ways away from Detroit, with minimal defenses. The supply convoy was attacked and forced back to Fort Niagara[9]. Approximately half of the member of the convoy were captured. On their way back to the outskirts of the fort, several of the soldiers attacked their captors, successfully freeing themselves and swimming to Fort Detroit with some of the supplies brought along by the convoy. Though the amount was likely not substantial; this delivery of supplies allowed the fort to more easily hold out while waiting for the next supply shipment.

In response to the rebellion and successful escape of several of the captured men, many of the captured members of the supply convoy were tortured, murdered, mutilated, and allowed to float down the river towards the Fort, in an attempt to scare the English into surrendering their fort. This was a horrible sight for the English to behold, their fellow countrymen, floating dead, their bodies having unspeakable things done to them before their death by the very same people that were laying siege to them, and if successful, would capture them, likely resulting in a similar fate. For these reasons, along with many others, this plan, however, backfired against the Native Americans, seeming to increase resolve within the fort; the English determination to hold out against the siege was stronger now than ever.

Another supply convoy, however, was quickly sent and reached the Fort successfully about a month after the first had been captured, at the end of July, 1763. There were two primary ships,The Huron and The Michigan, which together had materiel consisting of enough supplies to allow the fort to last out easily for the remainder of the year, if not until the next spring. They were also reinforced by several hundred English troops, whose commander convinced the leader of Fort Detroit that they should go on the offensive against Pontiac’s forces, and they set out from Fort Detroit with approximately 300 troops, determined to defeat Pontiac and end the siege on the fort[10].

As the troops set out from Fort Detroit towards Pontiac’s main encampment, they were spotted by persons allied to Pontiac, although it is unclear whether it was French settlers, or Native Americans who spotted the marching soldiers. As a result, the troops did not even make it to Pontiac’s encampment– They made it only a few miles before being ambushed and attacked by Pontiac’s forces. The English were defeated, and approximately only 60 soldiers returned to the fort–this is now known as the Battle of Bloody Run[3]. Enough soldiers remained and returned in the fort, however, to prevent a decisive end to the siege by elimination of British forces. As such, the siege continued to drag on.

As the summer began to come to a close, many of the people whom had committed themselves to assist Pontiac began to abandon this commitment and return to their respective villages. The harvest season was fast approaching, and many of them were needed back home to assist in cultivation and in the general preparations for the fast approaching, harsh winters of the Great Lakes region. Thus, a slow drain in the numbers of troops under Pontiac’s direction began, which would eventually lead to the collapse of the siege.

Later that year, the English and French signed a treaty with one another. As a result, the French, whom had been assisting Pontiac in his anti-British activities, could no longer send support to the Native Americans. This was the last straw; as many of his troops had returned home, and he could no longer rely on French support for supplies, he requested that peace between the natives of the fort and the attacking natives be negotiated. This request was forwarded to General Amherst, as the leader of the fort said he did not have the authority to negotiate such a peace. Pontiac then returned back to his home village. Thus the siege had come to an end, in less than a year.

The Bigger Picture

The siege of Fort Detroit was not the only attack on English Forts on the area, although it was one of two forts that were laid siege to, but that were ultimately unsuccessful. At the same time as Pontiac mounted his siege on Fort Detroit, a number of his compatriots attacked smaller forts throughout the Great Lakes region, including Fort Miami, currently known as Fort Wayne, and Fort Sandusky, both located just to the south of Fort Detroit. A fort further north, Fort Michillimackinac, was also attacked and seized by Native American Forces. There were also a number of attacks on forts in the eastern colonies, such as Fort Pitt. Being blamed for causing the uprising, General Amherst was recalled back to London, and replaced by General Thomas Gage. In 1764, General Gage sent two separate missions to take back the areas conquered by, and subsequently crush, the Native American forces. This move has been criticized by some as prolonging the war, although eventually the Native Americans were to capitulate[7].

Late in 1764, a treaty to end the Rebellion began to be negotiated at Fort Niagara, although it would not be signed there. A treaty would eventually signed in New York at Fort Ontario. Although considered by many to have been a surrender by the Native American forces; the reality is far from clear. There were no lands surrendered, and no prisoners returned[5]. The general conflict can be seen largely as a stalemate– no side came out on top.

After the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War and the Treaty of Paris, the British sought to revise their policies regarding the Colonists and the Native Americans. Many people of the time, as a result of the rebellion, had come to the conclusion that most Indians were subhuman; indeed the worst of Indian-American relations and opinions of one another was during the rebellion[5].

As a result of this, the English Crown had decided that the Colonists and the Native Americans were to be kept apart from one another, and thus imposed the well known policy that the western border of the colonies was to be the Mississippi River; sometimes referred to as establishing an “Indian Reserve” west of the river, and is commonly referred to as the “Rights of the Native Americans”, this policy was outlined in a Royal Proclamation in 1763. This was a policy that would eventually become one of the many grievances that lead to the American Revolution against the British[4].

The Native Americans of the 19th and 20th centuries both saw Pontiac’s Rebellion, and seized upon it as an example of the potential power of uniting their tribes against hostile American interests. Similar coalitions would be formed; from Sitting Bull at the battle of Little Big Horn, to Tecumseh in the War of 1812. It was an example of people setting aside their differences to preserve their way of life; and although in the long run it did not do much to help the Native American position in the Americas, it showed the colonists that they could not just trample over the Indians as though they were not there, without risking violence in return.

The rebellion, which was the first major effort against European Colonization in the Americas; has gone down in history as an Indian opposition to British rule in general. In reality, this was only a minor factor; the racist policies enacted by the British, especially after the generosity of the French in comparison, was the key factor in the deicison to rebel. And although unsuccessful, it will be viewed on for years to come as an example of a people fighting to preserve their very way of life, as people coming together, despite their differences, large and small, to fight under a common banner or a common cause. And in this way, along with others, Pontiac’s Rebellion will remain as an example of unity in an ever more divided, yet interconnected, world, an example, despite the barbarity of some of the acts during the siege of Fort Detroit, as an example of some of what is good within the human species; the ability to come together, to overlook hatred of another, to work towards a common goal.

Sources

Primary

[1,2] Letter from Colonel Henry Bouquet to General Amherst, dated 13 July 1763, and his reply, dated 16 July 1763. Both are retrievable at University of Massachussets Amherst

[3] Family Records and Events:Compiled Principally from the Original Manuscripts in the Rutherfurd Collection. L. Rutherfurd, 1894. Pg.110-115

[4] The Royal Proclamation of 1763. Written by King George III, 1763. Transcript available at this site.

Secondary

[5] Sturtevant, William C. Handbook of North American Indians: History of Indian-White Relations. Vol. 4. Government Printing Office, 1978.

[6]Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. Vintage, 2007.

[7] Dowd, Gregory Evans. War Under Heaven: Pontiac, the Indian Nations, & the British Empire. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

[8 ]Mayo, Lawrence Shaw. Jeffery Amherst: A Biography. Longmans, Green and Company, 1916.

[9] Detroit Historical Society: An Encyclopedia Of Detroit, which can be found at Here.

[10] The People of Detroit: Pontiac. historydetroit.com, specifically located here.