In 1967 one of the nation’s biggest and most destructive riots broke out on what is now known as Rosa Parks Boulevard in Detroit, Michigan, lasting for nearly five days. The Detroit Riot of 1967, also known as the 12th Street Riot, began July 23, 1967. Over the course of five days 44 people were killed, 1,189 were injured and well over 7,200 people were arrested. Almost 2,500 stores were looted, and total damages estimated nearly $32 million. This is also one of the known instances in which federal troops, mainly the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were called to deal with an issue inside the United States. This riot was the largest urban uprising to date, until the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Detroit is also the only city in the United States to have had military called in on our own soil on three separate occasions.

Sunday, July 23, 1967

Police were called in to raid a club in the early morning hours, and arrested everyone inside. A total of about 80 people celebrating the return of two Vietnam War veterans, shortly police arrived on the scene and began to arrest everyone present at the club [8]. During this process a crowd outside the club began harassing and assaulting police officers. Soon the angry mob began bottles and bricks at the vehicles and officers trying to transport the recently arrested civilians. Violence escalated from that point onward. The size of the crowd grew from hundreds to thousands in a matter of hours.

Looting began soon after and there was an insufficient number of officers to quell the angry mob. Police Commissioner Ray Giradin notified the state police, Wayne County sheriffs, and the Michigan National Guard. The problem was that it was a Sunday and most of these men were not on duty at the time. It was many hours before any form of support arrived to help calm the crowds, but by then it was far too late. The first fires broke out later in the day but no firefighters could get through the masses of people and extinguish the flames. It was also on this first day at about 11:55 A.M. that the mayor of Detroit contacted the United States Attorney General to inform him of the situation [1].

Monday, July 24, 1967

Early in the morning after many communications back and forth between officials in Detroit and the Department of Defense, the Michigan National Guard stepped in to try and quell the riot. For a time it was believed that the National Guard, along with state and local officials, would be enough to end the riots [1]. As the day dragged on the riot seemed to grow in intensity as more looting, violence, and destruction occurred. Hundreds of fires were started and much of the area was covered in smoke and flames [10]. The most astonishing was the reports of snipers all around the area taking shots at any officers they could see. Around noon, the President gave the all clear to use federal forces in order to stop the riot. Men had already been marshalled at the Selfridge Air Force Base and were ready to be sent into the fray.

Tuesday, July 25, 1967

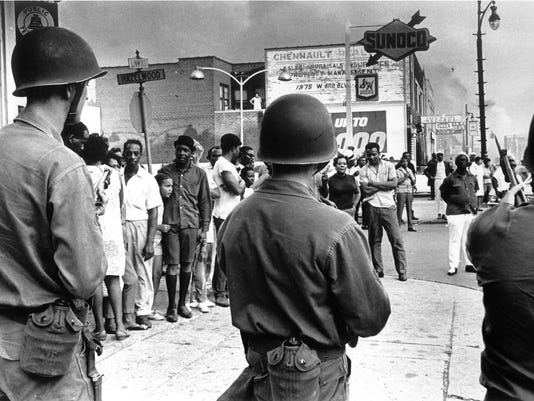

On this morning thousands of federal troops began to move into the city to help stop the riots. The men were told to use as little force as possible but were cleared to use lethal weapons such as bayonets and real bullets at their commanding officers’ discretion.

At this point the police forces were nearly out of steam. This caused many problems for both sides of the conflict. Since most of the police had been out in the conflict for a long period of time, officers had grown tired and angry. Police brutality reports were widespread. Although the rioters were mainly blacks [6], there were reports of white people being abused by police as well [10]. There were nearly seven thousand arrests this day for sniping alone, although none of these “snipers” were ever actually prosecuted. There were also many incidents of police and federal forces raiding homes and searching civilians for weapons without probable cause.

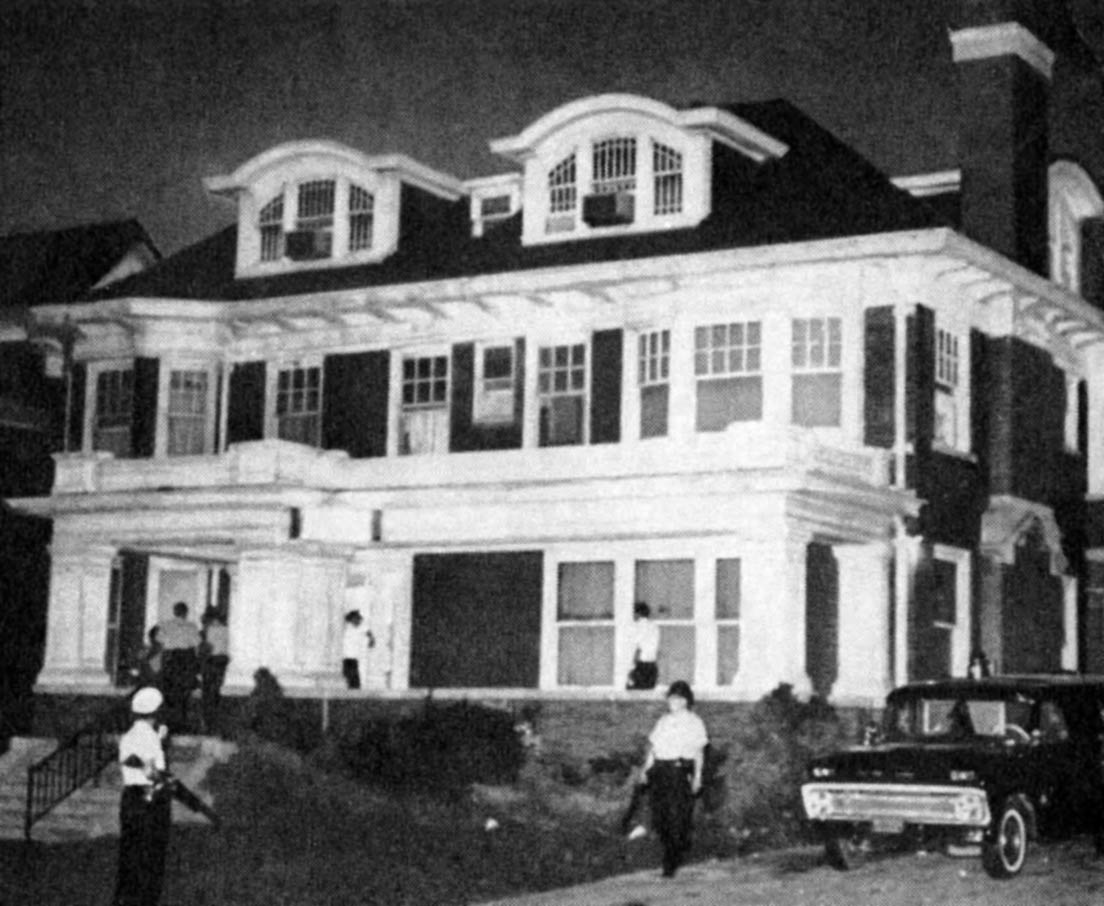

It was also during this time another infamous event occurred, the Algiers Motel Incident. Police officers killed three young black men in hotel room and later tried to cover the whole situation up. On this night police and the national guard stormed the Algiers Motel and searched the place looking for snipers. The police officers were using unethical practices in order to try and get patrons at the motel to give up a non-existent sniper. In the end three young black men were found dead and many others were badly beaten [4].

Wednesday, July 26, and Thursday, July 27, 1967

At this point the riots were beginning to slow down due to the combined efforts of the local and state police, and the federal forces sent in on Tuesday. Throughout much of Wednesday nothing really changed. Thursday however brought many new changes to the situation. Since conditions were looking better both state and federal officials decided that order could soon be restored and order all their men to sheath bayonets and remove ammunition from their weapons. This is also the day reports of sniper fire ceased in the city as well. Governor Romney even lifted the curfew that had been in place since Monday but later reenacted it. Not due to rioters but others that were trying to photograph and view the wreckage left in the wake of the riot. Then on Friday, the situation seemed so in hand that federal troops began to withdraw from the city [1]. All army troops were withdrawn by Saturday.

The Aftermath

In just five days so much death and destruction occurred. It was reported that 43 people were killed in this incident, thirty three were black and 10 were white. Of the white deaths that occurred there was one Detroit police officer, two Detroit firefighters, and a Michigan National Guardsman [7]. 1,189 people were injured, 407 civilians, 289 suspects, and the rest are police, firefighters, and military servicemen. The number of arrests were quite shocking: 7,231 people were arrested in total. Due to this insanely large number many makeshift jails were created in order to hold all of these people. Though nearly half of them had no prior criminal record. Most of them were charged with looting and a fair few with violating the curfew. Economically, this riot was one of the most destructive in United States history. Over 2,500 stores were destroyed, hundreds of families left homeless after hundreds of their homes and buildings were burned to the ground [10]. At the time it was estimated there were nearly $40-45 million worth of damage done to this portion of the city, over $132 million today.

Stories from the Riots

Recently museums and the historical society in Detroit have been asking for anyone that remembers anything about the riots to come forward and tell what their experience was like. One such story comes from an interview in the Detroit Free Press. A woman named Jackie DeYoung was just a girl fresh out of college at the time and she had just gotten a job working in the office of the police commissioner, Ray Giradin. She said when the riots broke out,

“I don’t recall anyone in the office debating about why it was happening. We were all just on the side of, let’s get things calm again.” She also remembered members of the community trying to help officers saying, “People were coming to headquarters and bringing food because we were all working such long shifts.” [2].

Another story that was submitted was from a 69 year old man by the name of Ted Van Buren. Van Buren was working as a lab tech at the Detroit Medical when the rioted erupted outside and they workers were told it was not safe to go home. He stayed at the hospital with many other doctors and nurses nearly the entire five day period. He stated,

“You stayed and you slept there and you did whatever was needed. Normally, I was a lab technician, but that week I covered the blood bank for the children.” Van Buren also tells historians about how the riots effected his family and his community, “My grandmother was really terrified. She had a beauty shop down on Hastings and Theodore and (looters) just came in and took what they wanted. … You got to remember, you’ve got a lot of good people that never would have committed crimes that got involved in that crowd and they just followed the crowd. A lot of good people got arrested. … The Afro Americans burned down their own neighborhoods. That was why it needed to be stopped. (12th Street) has never recovered [2].”

Primary Sources

- Cyrus, Vance R. “Final Report of Cyrus R. Vance Concerning the Detroit Riots.” Washington DC: Department of Defense, 1967. N.p., 1 Oct. 2008.

- Jesse, David. “Witnesses to History Tell Stories of Detroit Riot.” Detroit Free Press. N.p., 18 June 2016.

- Seeking Michigan. “Detroit Riot 1967.” Vimeo. Vimeo, Inc, June 26, 2009. Web

Secondary Sources

- Hagen, Charles M. “The Algiers Motel.” Harvard News. The Harvard Crimson, 12 July 1968. Web. 23 Nov. 2016.

- Fine, Sidney. “Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 54.4 (1990): 633-636. 14 10 2016.

- Singer, Benjamin D. “Mass Media and Communication Processes in the Detroit Riot of 1967.” The Publication Opinion Quarterly 34.2 (1970): 236-245. 13 10 2016.

- The Center for Michigan | Bridge Magazine. “A Quick Guide to the 1967 Detroit Riot.” MLive.com. N.p., 11 Mar. 2016.

- “1967 Detroit Riot.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 21 Nov. 2016.

For Further Reading

- The 12th Street Riot . n.d. 15 10 2016

- Detroit Race Riot (1967). n.d. 13 10 2016.