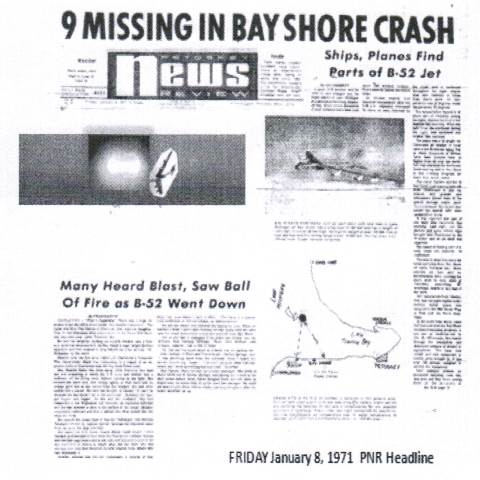

On January 7, 1971 a fireball erupted over the Little Traverse Bay caused by the crash of a Boeing B-52 Model C. Along with the fireball, a sonic boom carried the remembrance of “Hiram 16”, the call sign for the nine member flight crew that died in the tragic event. The B-52C and its crew were on a routine low level bomb training flight over northern Lake Michigan that day.

Strategic Air Command and the B-52

At the height of the Cold War, the United States Strategic Air Command (SAC) relied heavily on its ability to maintain a nuclear deterrent. The United States military utilized a triad system as a mechanism of “peacekeeping“.[7] [8] By maintaining the capability to wage nuclear strikes from bombers in the air, missile silos on land, and submarines in the ocean blue, the military was prepared to take a nuclear battle to whoever tests its will. A once classified historical summary of the Strategic Air Command stated its mission as:

“(TS) […] organize, train, equip, administer, and prepare strategic forces for aerospace combat, including offensive strikes, reconnaissance, and special missions. […] The command must maintain a high state of readiness to wage a strategic nuclear war, […], and be prepared to attack targets with nuclear and/or nonnuclear weapons”. [14]

The B-52 long range heavy bomber was an important asset in being able to carry out the SAC mission.[8] The B-52 dominated the air component of the triad system, allowing the military to deliver nuclear ordinance anywhere in the world. To maintain readiness, bomber squadrons routinely carried out training missions across the United States. These bombers were originally developed in the 1950’s for high-altitude flights (50000 feet) in order to have no risk of being shot down and tracked by radar. Unfortunately, by 1959, the Soviets improved their air defense capabilities and demonstrated operational use of it by shooting down a U-2 spy plane at 60000 feet over Soviet territory in May of 1960.[9] This incident led to a drastic revision in the penetration tactics of the high-altitude B-52s. The command at the SAC now re-purposed the B-52 from high to low altitude territorial entry at about 700 feet or less. Keeping in mind, these “winged-bomb-delivering-fortresses” were structurally designed and built to only fly at high altitudes, not 700 feet above ground! (For those interested in the B-52 check out the B-52 Stratofortress Association for more in depth information!)

“Bombs Away, Bomb Plot!”

To accommodate safe low altitude training flights, the SAC placed their eyes on a corridor over Lake Michigan for bomber flight routes. Since military jet engines of the time were not very efficient at low altitudes, a smoke trail would sometimes be left behind the aircraft leading to a unique name for the routes. These low level flight corridors became known as Oil Burner (OB) routes.[12] The new route the SAC was about to establish became known as OB-9. On orders from SAC headquarters in 1963, 1st Combat Evaluation Group Detachment 6, moved from Ironwood, Michigan to the town of Bay Shore in the Lower Peninsula to set up the Bay Shore Radar Bomb Scoring (RBS) Site.[12] From one little town to another, these small tight-knit Michigan communities were appealing to the SAC brass. The Bay Shore location was determined safe for accommodating the low altitude flights… unless, possibly, a nuclear plant was in the flight corridor!… Ironically – if you will – the RBS site in Bay Shore was established nearly a year after Consumers Energy stood up the nation’s fifth commercial nuclear plant. The Big Rock Point nuclear power plant was located only several miles west of the RBS site, making it an appealing “target” for bomb scoring … considering the time period and all. In April 1971 (a date AFTER January 7, 1971), a crash probability risk analysis delivered to Consumers Energy determined a 1.5 in 10 billion chance of a B-52 crashing into their nuclear plant. The story of the Big Rock Point nuclear plant and the low flying B-52s is uncovered in the article found here

Nuclear facility targets aside, bomb scoring was an operation used to evaluate the effectiveness of Cold War strategic bombers by simulating bomb drops with radar signals. These bomb drops were originally simulated at the regular high altitude flights, but following the early 1960’s, adapted to accommodate the low level entry. For bomb scoring, the RBS site and the B-52 crew would be in constant radio communication.[10] The two would communicate back and forth as the bomber approached its “target(s)”. Once the B-52 was within plotting distance of the site, the personnel there would begin tracking the aircraft. When the B-52 was ready to acquire its target, the crew initiated a radar tone. After the first tone, which normally lasted 20 seconds, the crew radios “Bombs away, Bomb Plot!” [11] followed by another radar tone which simulated the ordinance. The site uses the received pulses to track the course of the bomber and its “bomb” and ultimately determines where it would hit. The site then concludes whether the intended target would have been hit by the B-52’s ordinance. This was the exact mission for Hiram 16 on January 7, 1971.

“The Sun Doesn’t Set in the Northeast”

The SAC maintained an impressive bomber fleet in 1971, totaling around 741 airframes, give or take. All of the SAC’s B-52 Model C bombers were attached to Westover Air Force Base just outside Springfield, Massachusetts. This is where B-52C T/N 542666 was situated on the morning of January 7th. Mission planning and the crew briefing had taken place the day before. Signed off by Operations Officer, Maj Roger W. McCausland, the flight order had a nine member crew taking off from Westover AFB on a Combat Crew Training Mission (CCTM). The flight plan dictated the bomber was to fly OB-9, the route that flew over the Bay Shore RBS site. The CCTM included not only low level RBS runs but “minimum interval take-off, air refueling with a 35000 pound load, and celestial navigation” before landing back at Westover.[6]

Leading the crew, was Lt Col William B. Lemmon. Lt Col Lemmon had a total of 4469.3 flight hours in which 3127.5 were in the B-52. His most up to date flight evaluation, which turned out to be his last, was conducted on November 11, 1970. In his evaluation he received a 10/10 in all areas of evaluation except for 3 (a total of 21/24 items). He received a 9/10 in the latter. The evaluating instructor left notes such as “has excellent knowledge of applicable rigs and maneuvers” and “excellent [pilot] in all areas. very professional as an aircraft commander […]”. [6] Under supervision of a man with a near perfect record, the eight other crew members aboard B-52C T/N 542666 couldn’t have been in better hands. Awakening with adequate rest, the nine crew members were ready for their January 7th flight.

That afternoon, B-52C T/N 542666 sat on the tarmac third in line for the minimum interval take-off exercise, which was part of their flight order. Taking off just before 2 p.m. local time, the nine crew members aboard the bomber were in route to northern Lake Michigan. The taxi and take-off were accomplished without incident as expected. Shortly into the flight the bomber began its first air refueling exercise. During the exercise, Hiram 16 claimed it was undergoing a hydraulic leak. The crew noticed hydraulic fuel on a bulkhead in the crew compartment. Lt Col Lemmon advised the command that the leak was not serious and it would continue on but they would skip the second refueling exercise. This was an appropriate decision to make as the leak presented no serious hazard. The bomber and its crew continued toward Michigan where they would descend into the low level flight route, OB-9.

The weather at the time around the Bay Shore RBS site was a light snowfall with wind speeds of about 8 mph. The weather prevented no inconveniences to the crew, besides maybe the heavy coats to stay warm. As planned, the crew’s next objectives in the flight order included taking out four simulated targets – ECHO, FOXTROT, DELTA, and CHARLIE. In route for Little Traverse Bay, Hiram 16 prepared for its scoring runs on the targets at an altitude of approximately 700 feet. Right after 6 p.m. the bomber crew had completed their practice maneuvers and taken out the first two targets along their OB-9 route – ECHO and FOXTROT. After the run was scored reliable, the B-52 headed back toward the OB-9 entry point. Approximately a half hour later the bomber was ready to engage targets DELTA and CHARLIE. The crew of the B-52 provided the nominal radar tone and gave the verbal “bombs away, bomb plot!”, and DELTA was scored as another successful bomb drop. All that was left was hitting target CHARLIE. Another easy bombing run was almost over for the experienced crew. As the B-52 maneuvered and began to initiate the radar tone for CHARLIE, the Bay Shore RBS site lost contact with the crew. The RBS site tried continuously to regain contact with Hiram 16. Unbeknownst to them, they would not be receiving contact in return. A 7.2 million dollar, 450000 lb. aircraft just plunged into the waters of the Great Lakes.

A fireball erupted over Little Traverse Bay around 6:30 p.m. as B-52C T/N 542666 came to rest in the cold waters of Lake Michigan. The crash site was approximately 6 miles from the RBS site and 5 miles directly north of the Big Rock Point nuclear plant. Many locals, settling down for the night and preparing to watch the evening news, witnessed the sky light up and heard the cold air being cut by the sound of the blast. Local Air Force veteran, Herbert Cummings, who witnessed the crash stated it was the largest fireball he’d ever seen. Another witness, Mrs. Charles Bleha, who saw the orange glow from her home on the south shore of Little Traverse Bay, thought it was the sunset until she realized “the sun doesn’t set in the northeast“.[1] The U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) began an intensive search operation immediately after receiving the news from numerous phone calls.

The Search Begins …

The USCG’s initial search operation located nothing significant. The search was conducted with two of their surface vessels and helicopters, along with a foot search on the coast line the following day.[2] [3] The crew members were not located and only a small amount of debris was recovered in the initial search.[4] [5] Due to the B-52 being a Strategic Air Command asset, and more specifically, an Air Force asset, the U.S. Air Force Accident Investigation Board (AIB) took the lead into investigating the cause. The AIB called upon the U.S. Navy Supervisor of Salvage (SUPSALV) to provide their diving and salvage capabilities. The SUPSALV requested the assistance of a private firm, Ocean Systems, Incorporated (OSI), to aid in the search and salvage operations. With all the personnel involved in the operation present in the Bay Shore area, the search got underway on January 11th. According to the official U.S. Navy salvage report, the wreckage area spanned 2400 yards by 1600 yards, drastically increasing the difficulty of being able to retrieve the wreckage pieces.[13] Reported in the Petoskey News Review, a spokesperson for OSI stated they would not be able to estimate how long the search would take due to the scattering of debris and the weather conditions they were dealing with. Over the next two weeks, small pieces of wreckage were acquired, but still provided little insight to the cause of the crash. The question of whether to continue or not was tossed between the Air Force and SUPSALV until Mother Nature made the decision for them on January 25th. A blizzard struck the Little Traverse Bay community and the Michigan winter took over. The Accident Investigation Board, knowing they would not be able to reach any conclusions in the mid-winter season, called off the operation until May – ending “Phase I”. Spokesperson for the investigating team, Capt Leo Sanchez came out and reported to the public that all practice bombing runs were “called off for a while” [3], only referring to low level training routes. High altitude flights would still continue in the shadows. When asked about the cause of the crash, Capt Sanchez responded with “there could be 1,000 different reasons, maybe more” [3], and that the team will keep working tirelessly to find the answer. The AIB, with the debris found in Phase I, found the most probable cause to be “material factor of an undetermined nature”.[6]

A Tragic Retirement

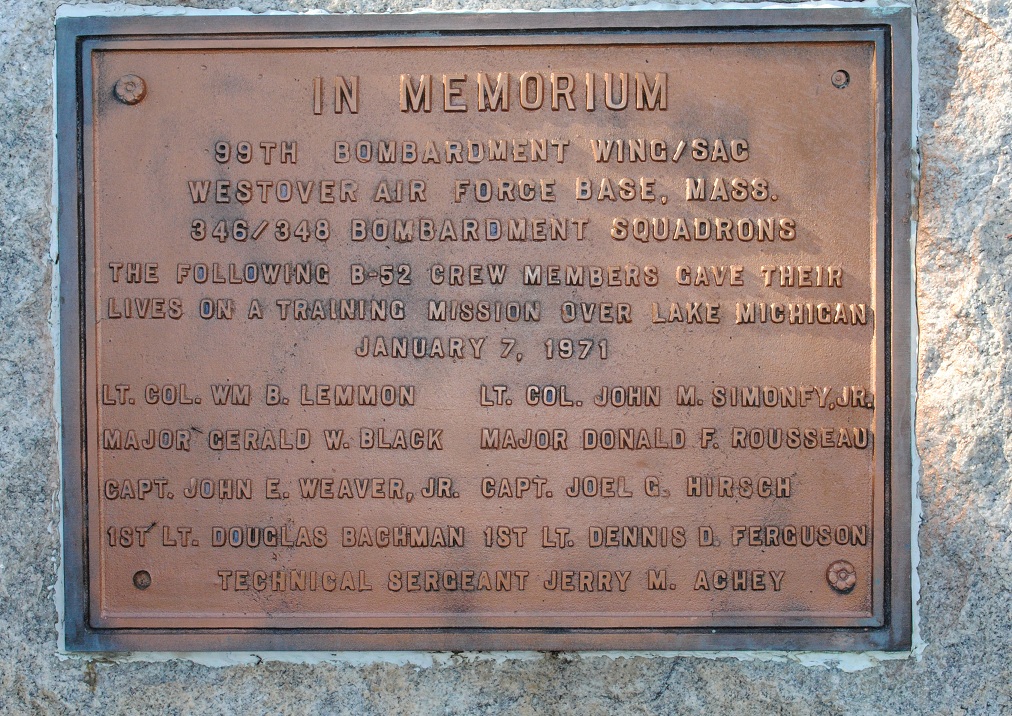

Phase II commenced in full force in late May and continued into early June. OSI personnel returned to Lake Michigan ready to conquer and within a few weeks, despite occasional battles with Mother Nature, they recovered all pieces large enough to be brought up from the bottom of the bay. What concluded Phase II was the scrapping of the bay’s bottom to retrieve the smaller remains. Once the salvage operation terminated, the bomber’s puzzle pieces were brought to Kincheloe Air Force Base in Kinross, MI where the AIB began to examine the wreckage in depth. Rummaging through fuel cells, wing skins, wing flaps, hydraulic fittings, landing gears, and more, Air Force investigators tirelessly fought to determine the cause of the crash. Making a pre-assumption early after the crash of mechanical failure, the AIB found themselves in déjà vu. A revised report after further investigation at Kincheloe AFB concluded the plane suffered metal fatigue that caused wing failure. The B-52 Model Cs, designed in the mid 50’s and originally constructed to fly at 50000 feet, found themselves conducting training operations between 500-700 feet – more often than not – between 1963 and 1971. The B-52C outlived its service and essentially “committed suicide”.[9] Following the investigation results being presented to the SAC brass, the remaining B-52 Model Cs at Westover AFB were retired and sent to “The Boneyard”. Unfortunately, B-52C T/N 542666 had to retire from service in the most tragic of ways, taking nine brave patriots with it. The nine veterans aboard that training flight fought in combat during the Vietnam War and continued their service in protecting the nation during the brink of nuclear war. These brave veterans, part of the 346/348 Bombardment Squadrons, were:

- Lt Col William Lemmon, 38, Pilot

- Lt Col John M. Somonfy Jr, 39, Navigator Instructor

- Maj Conald F. Rosseau, 37, Electronic Warfare Officer

- Maj Gerald W. Black, 32, Radar Navigator

- Capt John E. Weaver, 27, Navigator

- Capt Joel G. Hirsh, 26, Electronic Warfare Officer

- 1st Lt Douglas Bachman, 25, Co-Pilot

- 1st Lt Dennis Ferguson, 25, Navigator

- TSgt Jerry M. Achey, 33, Gunner

May the nine valorous men who lost their lives in the crash that frigid January evening rest in peace. To preserve the memory of the event, the crew is memorialized on a stone in the Lake Michigan Shore Roadside Park north of Charlevoix, MI on US 31.

Primary Sources:

- Fran Martin, “Many Heard Blast, Saw Ball of Fire as B-52 Went Down,” Petoskey News Review (Charlevoix, MI), January 8, 1971, 1

- Jim Doherty, “Ships, Planes Find Parts of B-52 Jet,” Petoskey News Review (Charlevoix, MI), January 8, 1971, 1

- Jim Herman, “Race Ice in Search For B-52, Crew of 9,” Petoskey News Review (Charlevoix, MI), January 12, 1971, 8

- Unk, “SAC B-52 Crashes in Lake Michigan,” Chicago Tribune, January 8, 1971, 4

- Unk, “Start Electronics Search For B-52 Lost Off the Bay,” Petoskey News Review (Charlevoix, MI), January 11, 1971, 1

- United States. Department of Defense. Department of the Air Force. United States Air Force Accident Investigation Board Report T/N 54-2666. Washington: U.S. A.F.D.P.O., February 1971

Secondary Sources:

- Karen J. Weitze, Cold War Infrastructure For Strategic Air Command: The Bomber Mission, (Califronia: KEA Environmental, Inc, 1999), [Prepared for Air Combat Command Under Contract: DACA63-98-P-1354]

- Richard H. Kohn, and Joseph P. Harahan, “U.S. Strategic Air Power, 1948-1962: Excerpts from an Interview with Generals Curtis E.LeMay, Leon W. Johnson, David A. Burchinal, and Jack J. Catton”, International Security 12, no. 4, 78-95

- Richard Wiles, “A Great Lakes Accident – Cold War Style”, Inland Seas 70, no. 1 [Provided Directly by Richard Wiles]

- Sigmund Alexander, “Bombing With the Beam”, AIR FORCE Magazine, June 2006, 80-83

- Sigmund Alexander, “The Ironwood Bomb Plot”, (The Stratojet Newsletter, July 2005, 9-10

- United States. Department of Defense. Department of the Air Force. Radar Bomb Scoring Records. Washington: U.S. G.P.O., 1977

- United States. Department of Defense. Department of the Navy. SALVOPS 71. Washington: U.S. G.P.O., 1972 [Document Number: NAVSEA 0994-012-6030]

- United States. Department of Defense. Department of the Air Force. Strategic Air Command. History of Strategic Air Command – FY1969. Washington: U.S. G.P.O., 1970 [Document Number: 70-B-0001]

For Further Reading:

- Wikipedia article: 1971 B-52C Lake Michigan Crash

- News clippings of articles regarding early bomb scoring runs: Charlevoix Emmet History

- MHUGL post about the nuclear plant: Michigan’s Nearly Endured Nuclear Disaster

- Several links in article for other topics

- Additional sources used for this research:

- The Detroit News – January 1971

- The Detroit Free Press – January 1971

- United States. Atomic Energy Commission. Memorandum Correspondence. Washington: U.S. G.P.O., 1970-1971

- United States. Department of Defense. Department of the Air Force. Memorandum Correspondence. Washington: U.S. G.P.O., 1970-1971

- Clifford Miller, “A Case Study in Systems Analysis,” (Master’s thesis, Air Force Institute of Technology, 1972)

A special thank you to Richard Wiles, who helped tremendously in uncovering the details of the incident.