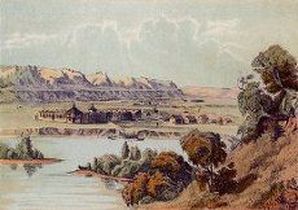

Built shortly after the War of 1812 and rebuilt 18 years later, Fort Crawford stood at the intersection of two of North America’s greatest waterways. At a time where waterways were the primary form of transportation, Fort Crawford secured American control in the Great Lakes region. Although the location was ideal, the fort was insignificant. The institution was operational between the War of 1812 and the Mexican War, a time referred to as Thirty Years Peace. Troops stationed at Old Fort Crawford primarily kept the peace between Indians and settlers. The largest conflict to involve southwestern Wisconsin was the Black Hawk War which occurred after the New Fort Crawford had been built. (Prairie du Chien Historical Society)

Early Prairie du Chien

Since 1608 when Samuel de Chaplain established the first permanent settlement in Quabec, New France had been infatuated with the mysteries of the Great Lakes and Mississippi waterways. Although many men had ventured south into the New World via these waterways, Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet were the first to document their voyage and are therefore accredited with the discovery of the great river. (Kellogg, p. 223)

“By 1673, the year of their departure, the time was ripe for a definite voyage of discovery… All New France believed in the existence of a great river draining to the west or south, beyond the rim of the Great Lakes. Expectation of immediate access to the South Sea had diminished, and a route to China was less eagerly sought than a vast new hinterland to explore and occupy.” (Kellogg, p. 223)

In early June of 1674, Marquette, Joliet, and five additional Frenchmen entered the Fox River and reached the Village of Maskoutens. Two Miamis Indians civilly consented to bring the seven

Frenchmen farther down the river. (Marquette, p. 234-235) After departure, the natives assigned to guide them on their journey “could not sufficiently express their astonishment at the sight

of seven Frenchmen, alone in two canoes, daring to undertake so extraordinary and so hazardous an expedition” (Marquette, p. 235) The two guides brought them to the Fox-Wisconsin Portage, where after ensuring the Frenchmen made the 2,700 pace portage, returned home. The crew continued onward by means of the wide and sandy Maskousing River, today called the Wisconsin River. “[They] safely entered Mississippi on the 17th of June, with a joy that [he could] not express.” (Marquette, p. 236)

Marquette and Joliet continued their expedition down the Mississippi River and more French voyagers followed. In 1685 a fur trading post was built in Prairie du Chien by Nicolas Perrot. Well into the 18th century, French travelers continued to visit regularly to trade; however, the French could not manage to maintain control over the land. After the French and Indian War, the territory was seceded to the British in the Treaty of Paris of 1763 which ended the French and Indian War. (Prairie du Chien Historical Society)

Driven by fur trade, British continued to occupy northwestern United States even after the Treaty of Paris of 1783 was signed which ended the Revolutionary War. In 1814, American forces decided to gain control of the region, realizing that British command could easily attack St. Louis. The construction of Fort Shelby in Prairie du Chien began. Its location was ideal for transportation. Along the banks of the Mississippi River, boats could travel south to the Gulf of Mexico or west to the Rocky Mountains. The Fox River flows into the Mississippi just south of Prairie du Chien which gave boats access to the Great Lakes. When word of American developments in the northwest reached the British at Fort Mackinac, they feared the British fur trade would be disrupted. The Battle of Prairie du Chien broke out on July 17, 1814 when British troops demanded that the American forces surrender. Upon their refusal, the British attacked the partially built fortification. Three days later American forces capitulated and abandoned the fort. In the spring of 1815, word of the Treaty of Ghent which ending the War of 1812, reached the British in the northwest. The northwest was now officially governed under American rule. The British were forced to relinquish control, doing so only after they destroyed the fort standing there. (Prairie du Chien Historical Society)

The Old Fort Crawford

American troops were quick to begin the construction of their own fortification. Built mostly from timber with the base of the walls constructed from stone, Fort Crawford was a square about three hundred forty to four hundred feet on each side. At the northeast, southeast, and southwest corners, blockhouses were built and supplied with cannons. “After the fort was complete [in 1817], troops spent their time in Prairie du Chien enforcing fur trade regulations and trying to keep the peace between oncoming settlers and the American Indians who had long made their homes there.” (Prairie du Chien Historical Society)

Less than two years later, in the winter of 1818-1819, Illinois was entered as a state into the union. The following spring, under the governorship of General Lewis Cass, county lines were established and blank commissions for the different officers of the counties were sent. Two companies of the Fifth Regiment of the U.S. Infantry were sent to occupy Fort Crawford under the command of Major Muhlenberg. The difficultly now would be to find people adequately knowledgeable with the business to fill the offices and perform the duties. (Lockwood, p. 115)

“Finally John W. Johnson…was selected as the Chief Justice of the County Court. [James H. Lockwood] was solicited to take the office of Associate Justice, or Judge of Probate, but…knowing very little about the proceedings of courts, and thinking that [he] had neither the practice nor dignity of hold a judicial office…[he] declined either of the judgeships, but accepted the office of Justice of the Peace.” (Lockwood, p. 115-116)

The two companies of troops at Fort Crawford received food rations from Pittsburgh. The rations were transported in keel-boats. Based on a Genesis Logistics Waterways Map the route was most likely west along the Ohio River and then north up the Mississippi River. The flour provided would be sour upon its arrival. Since “so much flour was made at Prairie du Chien at this time, that in 1820 Joseph Rolette contracted with the Government for supplying the…troops…with [the local flour], they preferring the coarse flour of the Prairie which was sweet, to the fine flour transported…from Pittsburgh.” (Lockwood, p. 114)

“There is a tract of land nearly opposite the old village of Prairie du Chien in Iowa, which was granted by Spanish Lieut. Governor of Louisiana to one Brazil Girard…but, in 1823, the commandant of Fort Crawford had a party of men detailed to cultivate a public garden on the old farm of Girard…” off the banks of the creek, usually called Girard’s Creek, that ran through it. (Lockwood, p. 118) Directed to supervise the party was Martin Scott. At this time, he was stationed at Fort Crawford and was then a Lieutenant of the fifth infantry.

Being a great marksman and fond of hunting, Scott would get into his little hunting canoe every morning and spend the day shooting woodcocks and, upon his return, would often boast of how many had bled that day. Eventually he began to call the creek Bloody Run. (Lockwood, p. 118)

“The name generally suggests to strangers the idea of some bloody battle having been fought there…A few years since the editor of [the] village paper had somewhere picked up the same romantic idea, and published a long traditionary account of a bloody battle pretended to have been fought there years ago. But the creek is indebted for its name to the hunting exploits of Major Martin Scott.” (Lockwood, p. 118-119)

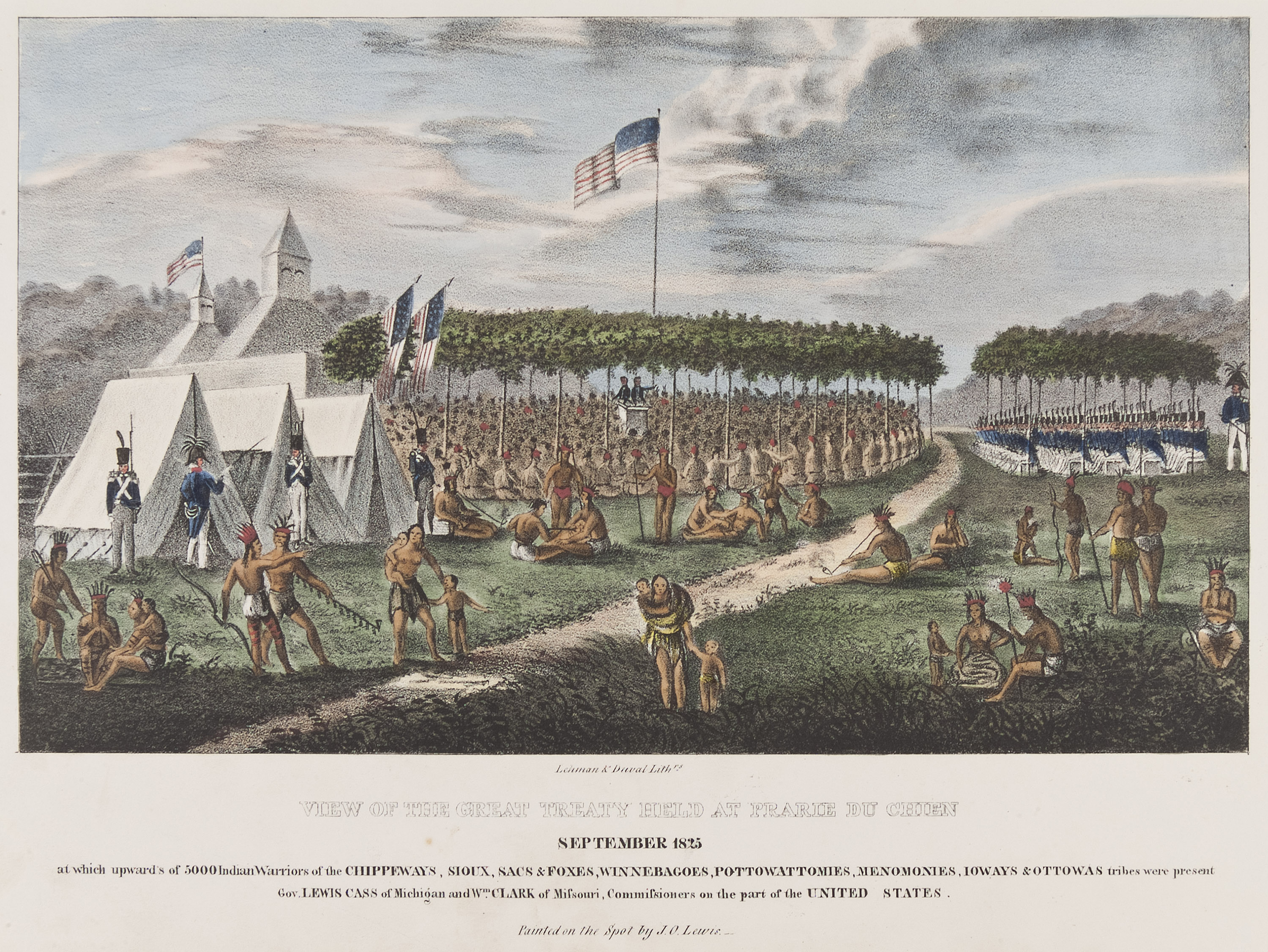

In the summer of 1825, Gov. Cass of Michigan and Gen. Clark, superintendent of Indian Affairs for Missouri were commissioners on the part of the United States in a grand council held with Indian tribes, Sioux, Sauks, Foxes, Chippewas, Winnebagoes, Menomonees, and Iowas. The numerous Indian nations represented made it “one of the largest treaty councils ever held in the United States.” (Prairie du Chien Historical Society) The objected of the council was to create a treaty to settle boundaries between the two parties. After boundaries were set between tribes the corps of surveyors were sent to review the bounds. That winter, the men at Washington, supposedly persuaded by Col. Snelling, thought it a good idea for the troops to abandon Fort Crawford and relocate to Fort Snelling. (Lockwood, p. 153-154)

Since mid-1822, Fort Crawford had been slowly battered by the Mississippi River flooding. At times soldiers’ quarters were immersed in three feet of water and troops were forced to camp on higher ground for extended periods of time. (Mahan, p. 87) The fort was slowly decaying. In October of 1826, an order directing the commandant of Fort Crawford to abandon the fort arrived. The troops were to go to Fort Snelling in Minnesota. Unless transportation could be secured, the provisions, ammunition and fort were to be left under supervision of a citizen. (Lockwood, p. 154)

However, a few days before this order was received, “there had been an alarming report circulated, that the Winnebagoes were going to attack Fort Crawford, and the commandant set to work repairing the old fort, and making additional defenses.” (Lockwood, p. 154) Once the order to abandon the fort was received, work was stopped and the order was carried out. The suddenness of this action was communicated to the Winnebagoes which caused them to believe that the troops had fled in fear of them. (Lockwood, p. 154) The fort remained empty for the next year, until in 1827 when three Indian men had murdered two settlers in Prairie du Chien. (Lockwood, p. 161-162)

These murders set fear of an all-out war with the Indians. Before “Col. Snelling could come down the Mississippi with two companies of the fifth regiment of the U.S. Infantry,” the settlers of Prairie du Chien under command of Thomas McNair took action. “It was immediately resolved to repair the old fort as well as possible for defense… Dirt was thrown up two or three feet high around the bottom logs of the fort, which were rotten and dry, and would easily ignite.” (Lockwood, p. 165) Despite the murder of citizens and movement of troops, the men in Washington decided that this was not an Indian war, a decision fortified by the surrender and imprisonment of Red Bird and two other young Indians. (Lockwood, p. 167)

After the Winnebago outbreak, Major General Gaines, the commander of the Western Department, inspected Fort Crawford. He deemed the fort inhabitable unless extensive repairs be made. Even then, “the barracks could not be rendered sufficiently comfortable to insure the health of the troops. The floors and lower timbers [were] decayed in part by the frequent overflowing of the river…Orders had been given…to repair the barracks…It [was] believed that the mechanics [at Fort Crawford would] be able to render the troops tolerably comfortable until the next spring” when it was feared that the usual flooding would occur. (American State Papers, p. 123-124)

The next spring more than one-fourth of the troops found themselves in the hospital suffering with ague and fever. In a report sent to the War Department in Washington in the spring of 1828, Major General Gaines clearly stated the need for new quarters at Prairie du Chien. (Mahan, p. 121) One year later, “the authorities at Washington had at length reached the conclusion that the old wooden barracks were no longer fit for occupancy.” (Mahan, p. 124)

The New Fort Crawford

The new Fort Crawford began to be built in 1830. The next year it was occupied by the healthy troops. The sick troops were left at the hospital in the old fort with the surgeons. Lockwood recalled the new Fort Crawford was finished in 1832. However, details continued to be finished into 1834. (Lockwood, p. 172) Major General Gaines proposed a design for the new fort in his report after informing the War Department of the suffering in Fort Crawford. Gaines proposed that “the work to be constructed should consist of two small stone towers or castles placed 120 feet apart, with the intermediate space filled up with a block of stone barracks.” The towers were to be 30 or 40 feet in diameter, two stories high. The barracks two stores high as well. (American State Papers, p. 125) The War Department disregarded his proposal. The New Fort Crawford was built from quarried limestone, timber, and stone. The barracks were single story, made of stone and occupied the east and west walls. The north and south walls “consisted of a stockade of pine logs…” (Mahan, p. 138)

The Black Hawk War began in April 1832 when Black Hawk decided to lead his native followers north to reclaim Indian lands in Illinois. During the war, the future president Zachary Taylor, then a colonel, was the commander at Fort Crawford. “Reinforcements were asked for from Fort Crawford, and Colonel Taylor moved down to Fort Armstrong with two companies of the First Infantry.” (Mahan, p. 167-168) The war ended four months later when Black Hawk surrendered to Colonel Zachary Taylor at the fort. After the Black Hawk War, troops at Fort Crawford continued to enforce the relocation of Indians. The last active troops were removed from Fort Crawford in 1856 and the fort was abandoned, leaving behind an institution that never was used to its full potential.

Primary Sources

- American State Papers, Military Affairs, Vol. IV. Pages 123-125.

- Lockwood, James H. “Early Times and Events in Wisconsin.” Second Annual Report and Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, for the Year 1855. (Madison: Calkins & Proudfit, 1856). Pages 98-196.

- Marquette, Jacques. “The Mississippi Voyage of Jolliet and Marquette, 1673” in Kellogg, Louise P. (editor). Narratives of Early American History, 1634-1699. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1917). Pages 223-257.

Secondary Sources

- Genesis Venture Logistics. “Genesis Logistics Waterways Map.”

- Prairie du Chien Historical Society. “History.”Fort Crawford Museum.

- Prairie du Chien Area Chamber of Commerce. “History.”Prairie du Chien.

- Mahan, Bruce E. Old Fort Crawford and the Frontier (Iowa City: State Historical Society of Iowa, 1926).

- Wisconsin Historical Society. “Battle of Prairie du Chien, 1814.”

For Further Reading

- Wikipedia. “Black Hawk War.”

- Wikipedia. “Siege of Prairie du Chien”