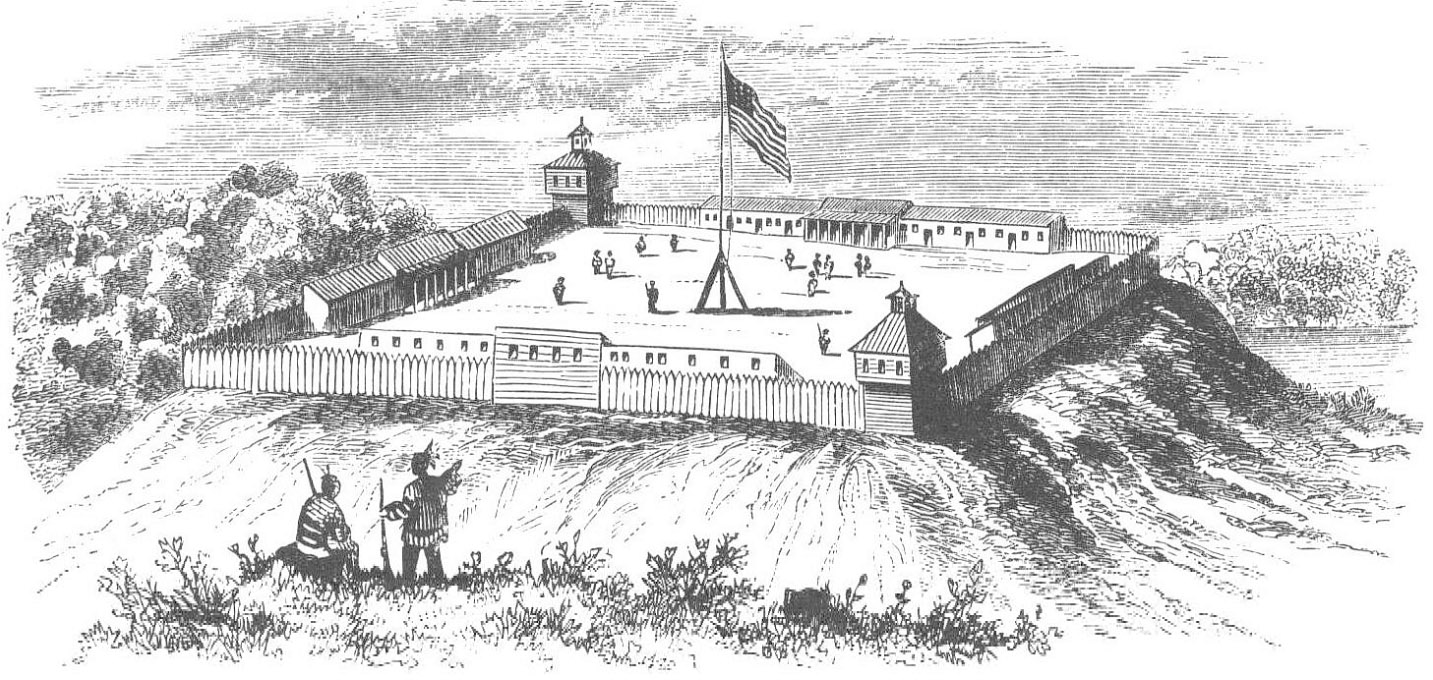

Fort Detroit would prove to be an important location for a series of attacks against the British during the War of 1812. The fort however would be put under the command of a General who would end up surrendering the fort to the British without putting up a fight. The Surrender of Detroit was controversial at the time by not only people who had fought with the general in the past, but by the troops under his command.

The 1812 Campaign and Those Involved

During the War of 1812, a strategy was drafted by General Henry Dearborn of invading Canada at three different locations simultaneously. The first of the three offenses was to have an army invade western Upper Canada and disrupt the British influence of the Native Americans. This offensive doubly served as a way to deny the British access to the Great Lakes during the war. A second central offensive aimed in the Niagara River region would disrupt access between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie as well as suppressing any Native American involvement. The third and final offensive would involve cutting off the St. Lawrence River between Lake Ontario and Montreal; with the capture of Montreal (the Canadian capital at the time) being the end goal. (Rauch, 14, 2013). The strategy was, on paper, an effective usage of the United States’ resources. The Great Lakes allow for an all-water way of connecting the Atlantic Ocean to as far as present day Thunder Bay, Ontario and Duluth, Minnesota. By disconnecting the two most important lakes to the British (Lake Ontario and Lake Erie), the US would have a greater opportunity at stalling the British long enough to seize the Canadian capital of Montreal and win the war.

The task at hand was a large one for the Americans. The American military wasn’t as strong as the British and was led by inexperienced and young generals. For the Americans, on the first offensive, President James Madison appointed General William Hull to command the troops in the Michigan Territory campaign. William Hull was the Governor of Michigan Territory and had proven himself militarily as a hero from the Revolutionary War (McNamara, 2017). His opposition was in the form on Major-General Isaac Brock for the British. Maj. Gen. Isaac Brock spent his life as a member of the military and arrived in Canada in 1802. At the time, his army consisted of low-morale, poorly disciplined soldiers, an inadequate amount of supplies, and even strained relations with the citizens (Rauch, 12, 2013). In 10 years’ time, Maj. Gen. Brock would shape his army into a well fighting unit that respected him. The dominating personality would prove to be his strongest quality as the troops knew what to expect from him. Isaac Brock came into Canada with a slew of problems but by the time of the War of 1812, he would have a respectable army at his disposal as well as having a thorough familiarity of the landscape, people, and his responsibilities.

Unfortunately for the British, despite being a military superpower during this time, they suffered from issues in the form of lack of manpower. Many of the British resources were being used back in Europe, combating Napoleon in the Napoleonic Wars; which started in 1803 and ended in 1815. In order to pad their numbers, the British made an alliance with the Native Americans residing in the Upper Canada and adjoining US territories. The leader of the Shawnee tribe was Chief Tecumseh. The Shawnee Leader supported the British war aim of attaining an independent Native American buffer state to stop the American incursion into the Northwest Territory. This wouldn’t be Tecumseh’s first fight with the Americans. In 1794, Tecumseh fought American troops during the Battle of Fallen Timbers near present-day Toledo, Ohio.

The Siege and Surrender of Detroit

The Surrender of Detroit occurred on August 16th but the few prior days sets up the scene for the surrender. Robert Lucas was a brigadier general in the Ohio Militia and accompanied Gen. Hull’s army during the Michigan Campaign. During his time, he kept a journal which gives some perspective on the campaign as well as the rationale behind the retreat. The following exert is from Robert Lucas’ journal:

[Thursday, August the Thirteenth]

“13th The British have taken possession of the Bank opposite Detroit and have commenced erecting a Battery, opposite the town, Lieuts Anderson and Dallaby each threw up a Battery on our side one in the Public Garden and the other Just below the town, — The British is Suffered to work at their batterys undisturbed and perhaps will Soon Commence firing upon the Town (Why in the name of God are they not routed before they compleet their Battery)…”

(Lucas, 60-61, 1906)

Even within the company, we see the questionable actions of Gen. Hull. The journal will mention that a detachment was assembled and prepared to rout the British. They awaited orders only to find Gen. Hull passed out. The British would end up completing the battery unit over the next couple days and sent a small convoy to the fort and the British “Summoned the Fort to Surrende[r] and had stated that their force was Amply Sufficient to justify such a Demand,” and that if the Fort did not surrender, then the “Town and Garrison would be massacred by the Indians.” (Lucas, 62). This demand was promptly refused. The Americans might have been less experienced, but they had a numbers advantage as well as an advantage in terrain, and the opposition having to attack a fortified position. In order for the British to take Fort Detroit, they would have to cross the Detroit River which poses a problem for the British. By negotiating in such a way to provoke fear in the enemy, it allows for the disadvantaged force to essentially “steal” the outcome of the battle. The British’s strategy was to bluff the size of their forces and the outcome and hope Gen. Hull didn’t call their bluff.

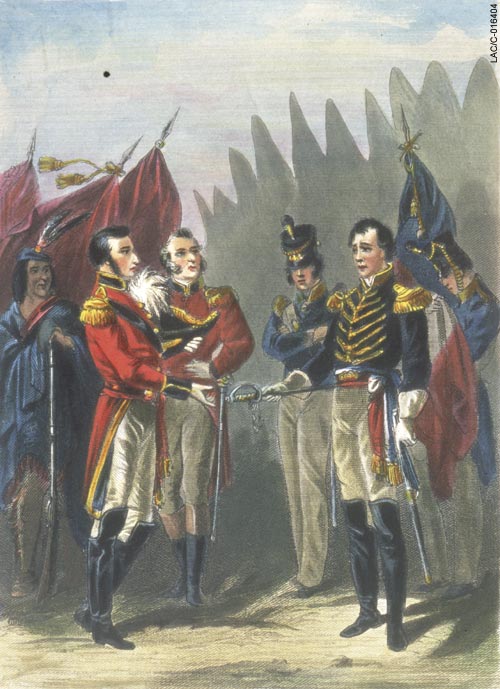

However, Hull would end up refusing their demands and this begins the Siege of Detroit. The British battery, which was allowed to be constructed, began firing at Fort Detroit on August 15th from across the river. British regulars, Canadian militiamen, and Indians advanced on Detroit as the guns of Amherstburg threw shells across the water (Taylor, 2017). From Gen. Hull’s point of view, it would seem like the British demand was holding its weight. The British threatened a massacre from the Indians and the British were softening the Fort for the inevitable massacre. Fearing a massacre from Gen. Brock’s Indians, Gen. Hull surrendered the Fort without putting up a fight (Donovan, 2017).

The surrender would cause much frustration in the American troops, as described by Robert Lucas:

“To See our Coulors prostitute to See and hear the firing from our own battery and the huzzaws of the British troops the yells of the Savages and the Discharge of Small arms, as Signals of joy over our disgrace was scenes too horrid to meditate upon with any other view than to Seek revenge… I Saw Major Wintherall of the Detroit Volunteers Brake his Sword and throw it away and Sev[e]ral Soldiers broke their muskets rather than Surrender them to the British.” (Lucas, 67, 1906)

The troops received orders from Gen. Hull to lay down their arms and uniforms. By laying down your weapons, you illustrate that you will no longer fight. Laying down your uniforms indicates that you recognize the better of the two forces and accept to be taken prisoner. The Native Americans forces plundered the houses and town and would help themselves to horses and other similar property. The British would end up capturing 2000+ troops, 60 pieces of Cannon of various sizes, 2 Howitzers (a type of cannon), 40 barrels of powder, 100,000 cartridges made up 400 rounds of cartridges for 24 ponders and a great quality of ball shells, and cartridges for the smaller cannon (Lucas, 69, 1906). Witnessing this isn’t something anyone would want to see. But the sting comes more due to the fact that not one shot was fired. The British hadn’t injured any Americans during the Siege of Detroit. Only a few injuries and one death occurred for the Americans as they were from the usual death and injury occurrences from handling a battery unit. Not one shot was fired yet the loss was heavier on the solders than if a battle had occurred. The disdain for the British was felt throughout the American forces. Soldiers breaking their swords and muskets as a protest to the British victory illustrates the frustration that was hanging over the heads of the American Troops.

Outcomes/Reactions of the Surrender

There are a couple of factors that come into play when looking at potential outcomes from the Surrender of Detroit. First off, the British were given ample time to set up their battery unit in Amherstburg. Had Gen. Hull sent out a unit to rout the British Battery unit, then the Siege of Detroit would have been avoidable. The British had to cross the Detroit River in order to take Fort Detroit. The battery unit was the support needed in order for the British to be able to cross the River. If the battery unit was routed, then the British forces would not have been able to successfully cross the river as the fire from the fort would have been focused on them. Couple this with the fact that the British were attacking a fortified position, the odds of success were incredibly small.

Another factor was if Gen. Hull had called the British bluff. The British tried frightening Gen. Hull in order to make up for their disadvantages. Had Gen. Hull called their bluff, the siege would have lasted longer than two days. Additionally, the Americans had around 2500 troops in comparison to the British who had 1400 men, not including Indians (UNITED STATES GAZETTE, 1812). The Americans would have been able to win this battle due to the sheer numbers advantage that they had. The outcome of the siege would have also been up in the air however as Fort Detroit was crowded with women and children and “the old and decrepit people of the town and country” (Rauch, 27, 2013). The Americans might have been able to survive the Siege and push back the British forces. However, they weren’t able to. This British victory would result in Maj. Gen. Isaac Brock to relocate his resources towards the Niagara River front.

The news outlets quickly caught wind of the surrendering from Gen. Hull. The Washington (Penn) on August 24th had an exert from a letter from Benj. Tappen, “I have received intelligence that on last Sunday, Gen. Hull and his army surrendered themselves prisoners of war, to our loving friends the British…” The New York Mercantile Advertiser had an exert from a letter dated Geneva, August 27th, “An express has this moment reached this place, announcing the capture of governour Hull, and all his army, in the fort at Detroit, to which place he had retreated…” (UNITED STATES’ GAZETTE, 1812). The surrendering of Gen. Hull was known by many, and as time shortly passed, more details emerged as the General had surrendered his entire army without putting up a fight. This creates a sense of disgrace to fellow Americans who would have fought the British at all costs less than a half century before. The Surrender of Fort Detroit disappointed his fellow soldiers, the public, and even those who served with Hull before.

Timothy Walker was another fighter in the Revolutionary War that the news of the Surrender of Fort Detroit had spread to. He wrote 2 letters directly to Gen. Hull to voice is disappointment in the General. In these letters, Timothy Walker calls out Gen. Hull for his cowardice. He personally attacks Hull and says that even if he had considered the lives affected by those related to the soldiers, that even something like suicide would just add to the guilt that he should be feeling. Timothy Walker writes:

“you did not only give up Fort Detroit… and the whole of Michigan Territory, but you gave up yourself, and a very respectable body of officers and soldiers that, in all probability, would have fought like a band of Spartans… Such are the men, sir, that you gave up to the disposal of a cruel and barbarous enemy, which you might, in all probability, have repelled and caused to retreat with great lose… if you had not approximated nigher [?] to the character of a traitor, or poltroon, than you did to that of a patriotic and bold commander. A shocking, shocking, laughable tale!” (Walker, 6-7, 1820)

General William Hull’s surrender to the British on August 16th, 1812 would leave a bad taste in the mouth of many Americans; both soldiers and civilian alike. William Hull would be returned to the United States in a prisoner exchange and was put on trial in 1814. While not convicted of a charge of treason, Willian Hull would be found guilty of cowardice and neglect of duty. He was sentenced to be shot and had his name struck from the rolls of the US Army (McNamara, 2017). President James Madison would pardon William Hull for his service in the Revolutionary War. William Hull would later retire and write a book defending himself and his actions during the Siege of Detroit. The memory of his surrender would live on and cause much debate for the continued decades.

Primary Sources

1. Lucas, Robert 1781-1853. [from old catalog]. The Robert Lucas Journal of the War of 1812 During the Campaign Under General William Hull. Iowa City, Ia.: The State historical society of Iowa, 1906.

2. UNITED STATES GAZETTE. “Many Early Reports on the Surrender of General Hull & Detroit to the British… .” UNITED STATES GAZETTE, 3 Sept. 1812.

3. Walker, Timothy. “Two Letters Addressed to General William Hull on His Conduct as a Soldier, in the Surrender of Fort Detroit to General Brock, without Resistance, in the Commencement of the Late War with Great Britain.” Received by William Hull, 12 Feb. 1820.

Secondary Sources

1. Donovan, Andrew. “Encyclopedia Of Detroit.” Detroit Historical Society – Where the Past Is Present, Detroit Historical Society, detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/fort-lernoult.

2. McNamara, Robert. “Surrender of Fort Detroit: Early Disaster for America in the War of 1812.” ThoughtCo, www.thoughtco.com/the-1812-surrender-of-fort-detroit-1773546.

3. Rauch, Steven J. The Campaign of 1812. Center of Military History, United States Army, 2013.

4. Taylor, R. “The Capture of Detroit, 1812.” The Capture of Detroit, 1812, www.warof1812.ca/batdetroit.html.

Further Readings

- Mywarof1812.com (Battle of Detroit)

- Wikipedia (Siege of Detroit)