George DeBaptiste was a prominent abolitionist and conductor on the Underground Railroad in his home in Detroit, Michigan. DeBaptiste was a catalyst for the American Civil War working with other nationally known abolitionists like John Brown, famous for his raid on Harpers Ferry, and Fredrick Douglass, a writer and escaped slave. DeBaptiste during the war acted as a recruiter in Michigan for the Union Army helping form Michigan’s first black regiment. DeBaptiste was not a soldier himself but instead chose to move with the regiment to act as a sutler, someone who provides provisions to soldiers, for the 102nd regiment that he helped create and inspire (Detroit Free Press, 1875)

BORN INTO FREEDOM

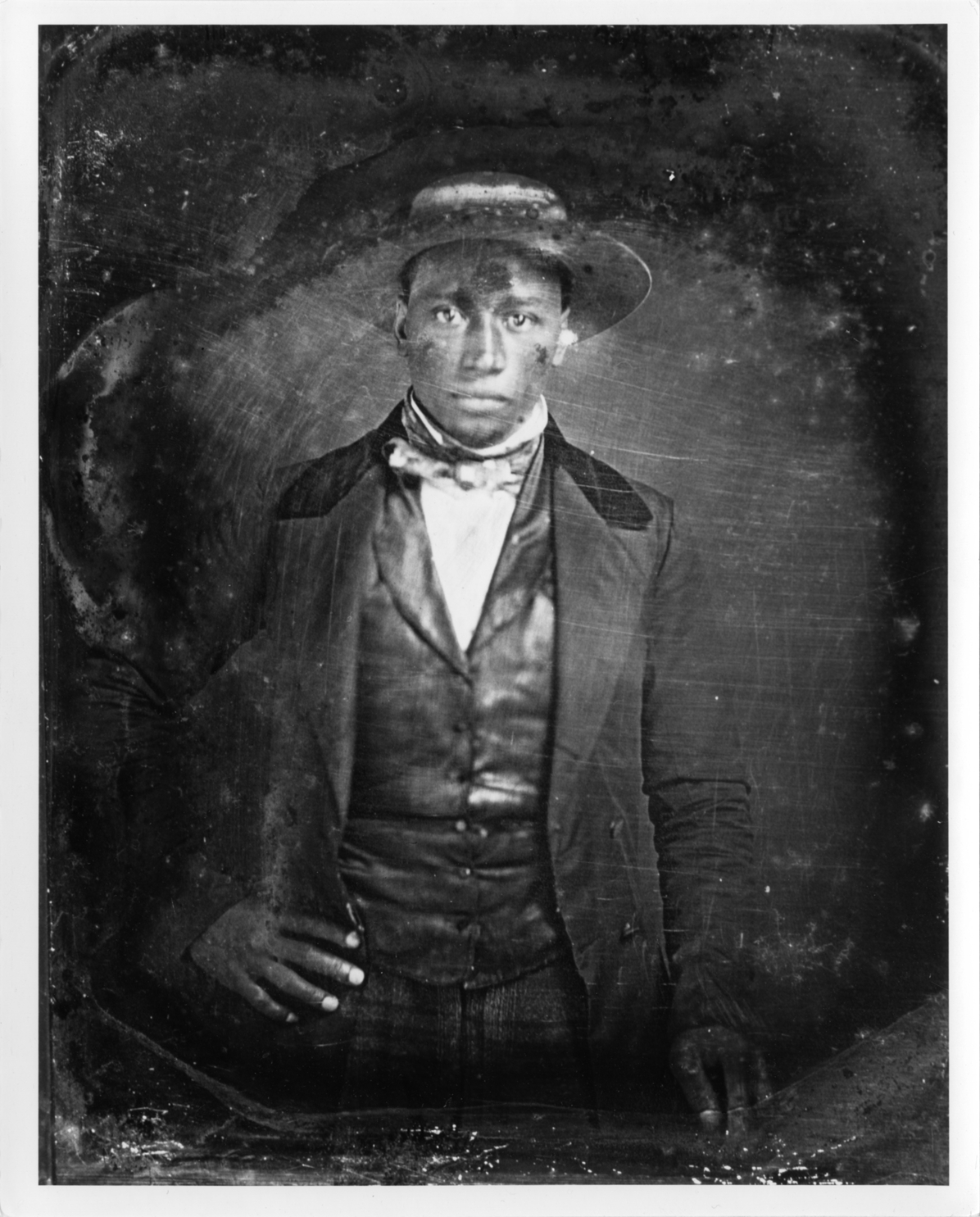

George DeBaptiste was an African American man born in Fredericksburg, Virginia in 1814 to free parents. George DeBaptiste never was a slave himself though he felt a deep connection with those who were. George attended a few years of school in his hometown of Frdericksburg, enough to read and write and preform basic mathematics. After schooling he apprenticed as a barber to learn a trade and eventually was a hired hand to many wealthy whites. One man George assisted was a Southern gambler and through this George traveled through the South. During this time George was treated not as a slave but as hired help and saw the true face of slavery (Detroit Post, 1870), (Detroit Tribune, 1886).

George then moved to Madison, Indiana in 1838 where he opened a barber shop and started a family. It was almost immediately that George started to assist escaped slaves. Madison is a border town located next to Kentucky, a slave state at the time. George helped slaves reach 12 miles across the Ohio river, away from Kentucky and into Indiana. George would stand by the river with a lantern and wait for any that needed his help. DeBaptiste had kept his certificate of freedom issued to him in his 20s to prove his free birth. DeBaptiste claimed to have used this 33 times to assist slaves which matched the description printed on it, mulatto skinned, about five foot seven and a half inches, and his birth date (Henderson, 2002).

George was soon suspected of helping slaves and was cited under black code laws for helping fugitives. George and his family faced expulsion form the state if these charges were met. George fought the Indiana Supreme Court over this matter saying that these laws were unjust and unconstitutional. George achieved a small victory, convincing the judges to allow him to stay in the state, however he did not convince them of the unconstitutional of the laws. Soon after the case the state of Kentucky put a $1000 bounty for his arrest. The news of the bounty and growing political tensions in the area inspired George and his family to leave Madison and find new work (Lumpkin, 1967).

George DeBaptiste was lucky enough to be invited to serve as a personal steward for Gen. William Henry Harrison in 1841. Harrison was later inaugurated as president of the United States and he and in extension George moved to the White House in Washington D.C. Gen. Harrison’s presidency did not last long, however, when giving his inaugural address in the rain he caught pneumonia and died in less than a month. George staying in Washington for less than 2 months in total and was left with no choice but to return to Madison for the time being. In Madison George was frequently a target for harassment and decided to move to Detroit, Michigan (Henderson, 2002).

There were many reasons for DeBaptiste to move to Detroit. Detroit was a border city much like Madison where DeBaptiste could continue work in emancipation. Detroit had a small but vigilant black community at the time of his move. This community can be described with the events of the Blackburn Riots which occurred a few years before DeBaptiste’s move. A man and woman with the name Blackburn, both fugitive slaves from Kentucky settled in Detroit seeking refuge. When their master arrived to lay claim to them they were arrested, jailed, and brought before a judge for sentencing. The black community was outraged and rescued the couple through subterfuge, force, and rioting. The couple were transported away to Canada though left Detroit in a state of disarray. The white community was in awe of the events, the black community in an outrage. The sheriff was badly injured in the riots and the Mayor called for Federal assistance in the form of the Company E 4th Artillery which were dispatched to act as a policing force. The company were given the orders to control “terror into which the citizens of Detroit have been thrown in consequence of some hostile movements of the black population” (Wright Museum).

BUSINESS IN DETROIT

In Detroit George was an instantaneous business success and a pioneer for African American owned business in Detroit. DeBaptiste became a co-owner of a popular barber shop and worked as a sales clerk in a downtown clothing store. Soon DeBaptiste has enough money to purchase a bakery in 1850. George used his business success to try to influence politics and promote emancipation (Detroit Post, 1870). George perused legal means to emancipate slaves and fought for African American voting rights acting as a delegate in political conventions, however the results were lackluster to George. With little change in politics George increasingly pursued illegal means of emancipation.

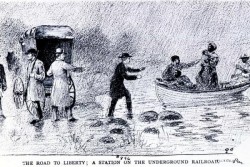

DeBaptiste sold his bakery and with the money bought a steam boat named the T.Whitney. Despite being the owner of the ship DeBaptiste could not captain it, George hired a white captain because black men were not legally allowed to captain ships. DeBaptiste used this boat for business as well as to illegally transport slaves across the US border into Canada.

To transport slaves DeBaptiste would take his “broken” wagon to a repair shop with a pro-emancipation owner. He would leave his wagon there while in the dead of night the slaves would move from DeBaptiste’s home or the 2nd Baptist Church into the wagon. The wagon was then covered in straw and horse manure. George would cover his horse’s hooves with carpeting to muffle their sound and transport the slaves to the T.Whitney where they were loaded on and marked on the international trade manifest as “Black wool”. DeBaptiste did this for years and it is unknown how many slaves he had helped escape to freedom. The Detroit Historical Museum estimates over 5000 slaves passed through the 2nd Baptist Church in Detroit.

ROLE IN THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

George DeBaptiste acted as a major part of the Underground railroad from the early 1830s into the 1860s. DeBaptiste acted as a manager of the Underground Railroad, a network of abolitionists designed to move slaves northward away from their southern oppressors. The railroad would communicate through coded messages in church sermons or posting disguised as notices to stockholders of a fake railroad. DeBaptiste was also involved in many more visible activism groups such as The Colored Vigilance Committee and The Negro Union League, often funding these groups from his own money gained through his businesses.

George was a member of multiple secret societies dedicated to anti-slavery activism and activity. DeBaptiste formed an organization that went by multiple names consisting of “The Order of the Men of Oppression”, “The African American Mysteries”, and “The Order of Emigration” (Detroit Tribune, 1886). These societies are believed to be quite large and allowed few white members. A member of this society, William Lambert, described the ritual used to confirm entrance into the society. A long ritual where entrants must memorize actions and oaths relating to revolution, revolt, and governance. Lambert described the ritual as being clad in “a good deal of frummery” in an interview with the Detroit Post in May of 1870. DeBaptiste thought this process necessary as the only members of the society must be “A man fit to be trusted with its unlawful secrets and tried in dangerous enterprise.” (Detroit Post, 1870).

It was in this society where George DeBaptiste met with famous abolitionist figures such as John Brown and Fredrick Douglass. John Brown and George DeBaptiste were in close contact with another and developed an intricate cypher for communication via telegraph. Messages sent regarding activities of the underground railroad were hidden behind common language. John Brown met with both George DeBaptiste and William Lampert in Detroit to discuss his plans for emancipation. John Brown believed that he could spark a rebellion in the south and that all free black men of the north would join his cause. His target was Harpers Ferry, West Virginia and he was determined to conduct a raid to muster support for rebellion. DeBaptiste thought his plan was misguided though failed to convince John Brown of its shortcomings. In October of 1859 John Brown conducted his raid and was small force was quickly overrun resulting in Brown’s execution (Mythic Detroit).

ROLE IN THE CIVIL WAR

John Brown’s actions are seen as a catalyst for the Civil War which started very shortly after. When the war began DeBaptiste, supporting the newly elected president Abraham Lincoln and his long time goal of abolitionism, began organizing the Michigan Colored Regiment. DeBaptiste acted as an organizer and by 1863 the regiment known as the 102nd U.S. Colored Troops had gained over 1400 volunteers. The regiment left Detroit fore service across the Southern states in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina and others. George went with the regiment as well not as a soldier but a sutler. DeBaptiste sold supplies to the regiment as well as being an unofficial figurehead. The regiment was disbanded after the war suffering casualties of about 150 men (American National Biography, 1999).

After the war George returned to Detroit and continued managing his thriving businesses as well as his activities with the underground railroad. The 13th amendment to the constitution was written but was not fully enforced in the south. DeBaptiste felt his duties in the railroad necessary until April 7th 1870 a few weeks after the 15th amendment to the United States Constitution was written giving African Americans the right to vote. George DeBaptiste put a final notice on his office building reading “Notice to Stockholders — Office of the Underground Railway: This office is permanently closed.”. George DeBaptiste died of cancer in 1875 survived by a son and daughter.

Primary Sources

- “Supplement: Underground Railroad. Reminiscences of the Days of Slavery.” Detroit Post, 15 May 1870.

- “Freedom’s Railway. Reminiscences of the Brave Old Days of the Famous Underground Line Historic Scenes Recalled.” Detroit Tribune, 17 Jan. 1886, p. 2.

- “Death of George DeBaptiste.” Detroit Free Press, 23 Feb. 1875, p. 1.

- “George DeBaptiste, His Death Yesterday.” Detroit Advertiser and Tribune, 23 Feb. 1875.

- DeBaptiste, George, et al. “Resolution.” Received by Family of Jacob M. Howard, 5 Apr. 1871, Detroit, Michigan.

Secondary Sources

- Henderson, Ashyia N. Contemporary Black Biography: Profiles from the International Black Community. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group, 2002.

- Lumpkin, Katherine DuPre. “‘The General Plan Was Freedom’: A Negro Secret Order on the Underground Railroad.” Phylon (1960-), vol. 28, no. 1, 1967, pp. 63–77. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/274126.

- “Debaptiste, George.” American National Biography. 6 (1999). Print.

- “George DeBaptiste, a Michigan Abolitionist.” African American Registry, www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/george-debaptiste-michigan-abolitionist. 2000.

- “The Detroit Gunpowder Plot – George De Baptiste, Frederick Douglass, and John Brown’s Raid.” The Detroit Gunpowder Plot – George De Baptiste, Frederick Douglass, and John Brown’s Raid — Mythic Detroit, www.mythicdetroit.org/index.php?n=Main.GunpowderPlot. 2012.

- “Blackburn Riots of 1833.” Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, http://ugrr.thewright.org/media/Pdf/Blackburn_Riots_of_1833_Events_UGRR_Final_1.pdf