The Rise and Fall of Little Crow:

The Dakota people led by Chief Taoyateduta (Little Crow) launched the U.S Dakota war of 1862 in Minnesota resulting in one of the deadliest Indian vs settler disputes to this day. On Monday August 18, 1862, Little Crow reluctantly pushed the rebellion which would last 6 weeks and kill more than 600. The rise of westward expansion also brought with it treaties between the U.S government and various Indian tribes exchanging land for goods, services, and protection. When the treaties parameters were ignored by the U.S. government, rebellions began.

Pre-War entanglements:

The Dakota which translates to the “allies” and later mispronounced the “Sioux” by the French, was a combination of “seven politically distinct tribes that shared the same cultures, social organization, and language” (5). Of the seven tribes, the Mdewakanton tribe led by Chief Little Crow, inherited premier lands which introduced the Sioux to an extensive trading program with the U.S. government. The Chief knew white expansion was inevitable so he bargained for the best possible deal for his people while still attempting to be friendly with the governors (2).

Between 1805 and the start of the war, many treaties were erected between the U.S. government and the Dakota. In exchange for land for new settlements and fur trades, the Indian tribes would receive money payments, goods, provisions, and protection. The Indians were told that if they signed the treaties they would be forever taken care of and provided for and if they didn’t sign than they would be driven out of their lands, starved, and killed off (7). The Indian people went on the American government’s word since they didn’t understand even half of what the treaties they were signing meant. As more and more treaties went into effect, the United States government were dishonoring money allocations while still continuing expansion into the Dakota Territory. This was further allocated by the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and those who refused were forcibly removed and pushed further westward to specific Indian territories (7). With increased migrations towards the Dakota Territory, the United States government secured little land for them and continuously renounced the land that was once promised to them. “Almost a stone’s throw of the reservation was the thriving town of New Ulm whose residents crowded upon the land procured in the treaty of 1858 for the Indian people” (3). When opposition arose over neglected treaty arrangements, the Indian people told the governors that the U.S. government could keep their money and the Indians would keep their land (3).

With less and less land and none of the money they were promised, the Indians were readily dependent on the U. S. government which had begun to separate the Dakota and unevenly distributing annuities. While the rest of the United States focused on the second battle of Bull Run taking place with the Civil War, Minnesota partook in a battle of its own (1). Lack of supplies, late and missing payments due to civil war preoccupations, and little land left to them, the Dakota had had enough and conflict was inevitable.

6 Week War begins:

On August 17, 1862, four Dakota men murdered five white settlers near Acton, Minnesota. The Dakota men returned to their village for protection and leaders tried to appeal to Little Crow to lead them in war on the whites (7). Many in the tribes didn’t want to fight the American numbers or risk the retaliation but the younger Dakota men wanted to retake back the land that was lost to them. The successful ambush of Captain John Marsh’s command convinced many of the once neutral Dakota men to join in the fighting (1). Reluctantly Little Crow led them into war. The next day, the Dakota attacked the Redwood (Lower) Agency of white traders and government employees and any relief forces sent from Fort Ridgely. In the days that followed, hundreds were killed in various battles.

Former trader, congressman, and Governor Henry Sibley commanded the U.S and led volunteer state militia against the Indian tribes. The Dakota made two attacks on Fort Ridgley before retreating and two attacks on New Ulm which was defended, barricaded, and evacuated. The Upper agency of Dakota formed a union that opposed the war and created the Dakota Peace Party and began negotiations with Sibley beginning in early September. “The last Dakota victory arrived on September 2nd, 1862 when warriors attacked and overran a burial party campsite leading to a 36 hour siege which only let up when relief arrived” (4). Little Crow continued skirmishes and attacks until Sibley defeated Little Crow’s forces at the final battle of Wood Lake on September 23rd. In the days following, Little Crow and his followers fled westward and the Dakota Peace Party surrendered the 250 hostages that were being held at Camp Release.

After Defeat:

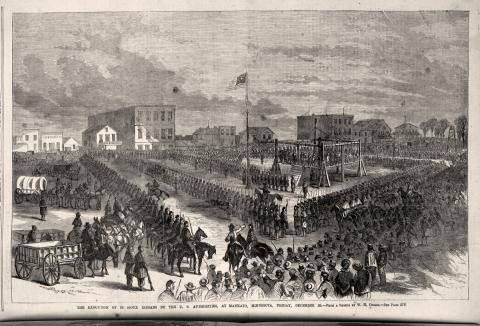

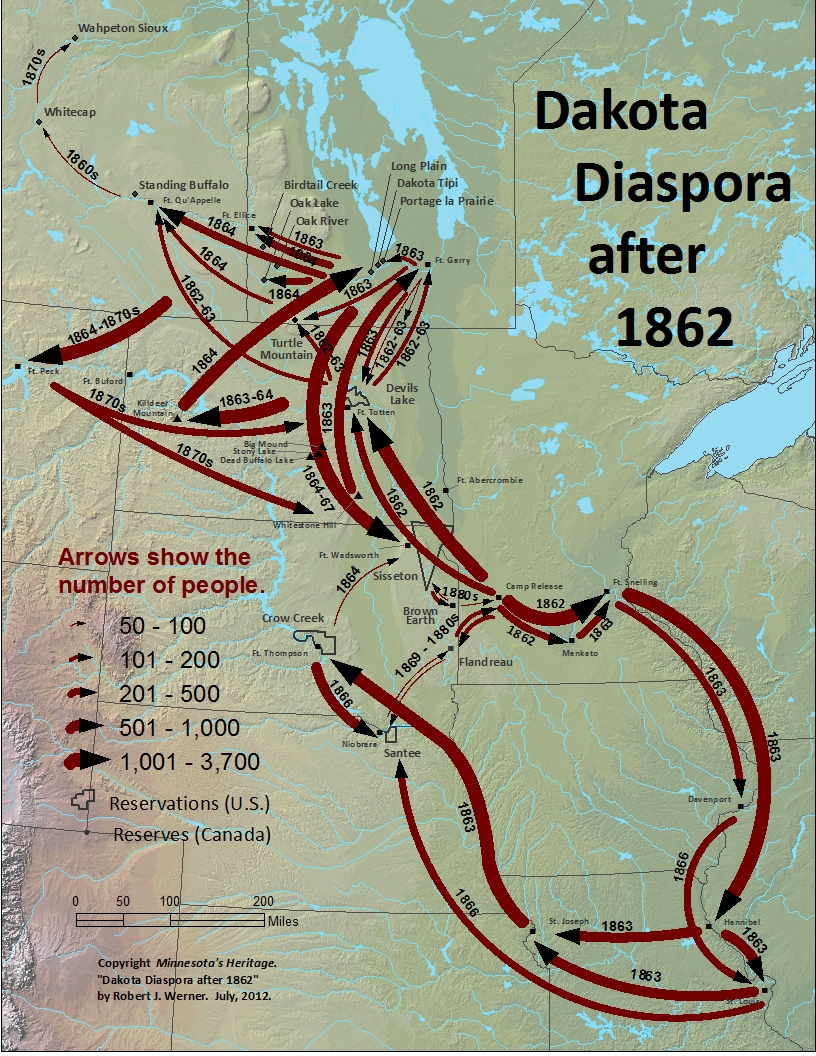

More than 600 Americans were killed during the war, many of which were unarmed men, women, and children. When surrendering, Sibley promised Dakota leaders that only those who had murdered would be punished. A six member commission was created in which all members had fought in the war with the Dakota. Trials began September 28th and resulted in 392 men tried and 323 convicted. Of the convicted 303 were to be hung and the rest imprisoned. Orders were given that none were to be executed until President Lincoln gave the approval. “Lincoln was torn between cries for vengeance and his concerns about potential injustice to the accused” (5). The people of Minnesota wanted actions and executions to begin and mob mentality began. Finally President Lincoln reviewed the cases of convictions and released a statement saying only 39 men would be executed. On December 26th 1862, 38 men were hung in front of watching soldiers and citizens near Mankato, Minnesota. This would be the largest execution in American Indian history. After exile from Minnesota, the Dakota were moved to reservations and were made to assimilate to American ways. The small percentage who had not been found guilty of participating in the violence were protected by the government (1). During the summer of 1863, an Indian was shot dead by farmers and when his body was brought into authorities, the body proved to be Little Crows who had been in hiding since the war. Few Dakota people remained in Minnesota after the war but some returned after exile and purchased land to rebuild the “sioux” community (7).

Primary Sources:

- Anderson, Gary Clayton and Woolworth, Alan R (1990). “Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862,” The Annals of Iowa 50, 681-682.

- Brown, Samuel J (April 6, 13, 20, 27, May 4, 11, 1897). “In Captivity: The experience, Privations and Dangers of Sam’l J. Brown, and Others, while Prisoners of the hostile Sioux, during the Massacre and War of 1862,” Mankato Weekly Review

- Heard, Isaac V. D. History of the Sioux War and Massacres of 1862 and 1863 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2015).

Secondary Sources:

- Brown, Curt. McClatchy (2012). “Retracing the War that Shape Minnesota”, Tribune Business News; web. Washington [Washington].

- Chomsky, Carol. The United States-Dakota War Trials: A Study in Military Injustice. Stanford Law Review, November, 1990.

- Minnesota Historical Society (2008). The US-Dakota War of 1862

For Further Reading:

- Lass, William E. “Histories of the U.S.—Dakota War of 1862.” Minnesota History, vol. 63, no. 2, 2012, pp. 44–57. print. JSTOR, JSTOR

- Klein, Jan, and Joyce Kloncz. “Family and Friends of Dakota Uprising Victims.” Family and Friends of Dakota Uprising Victims, 2012, web. www.dakotavictims1862.com.