Overview

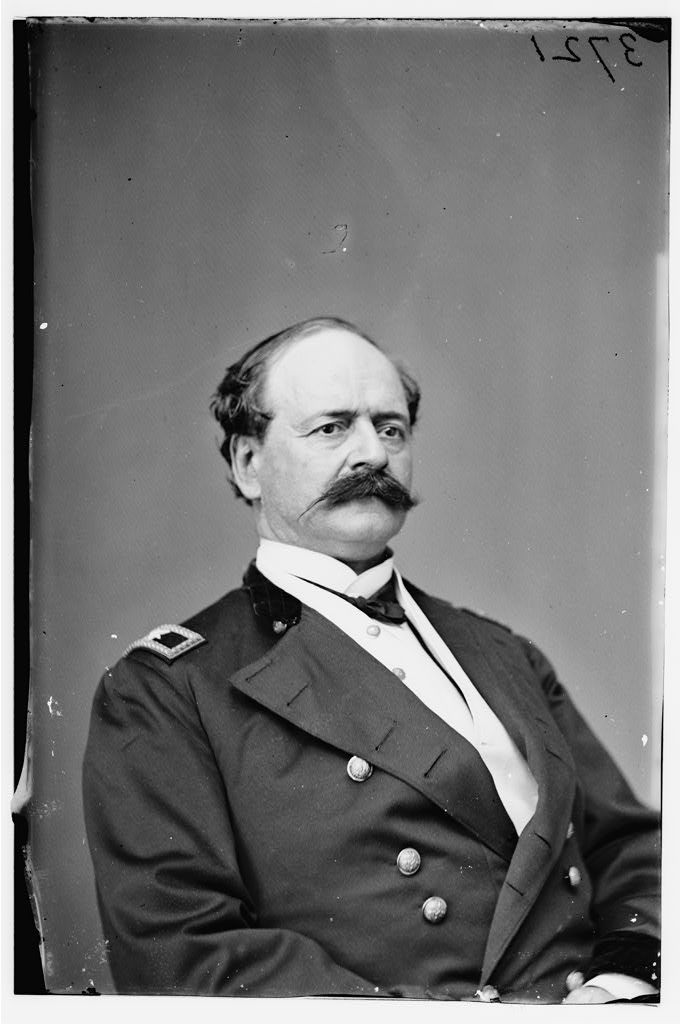

Henry Dwight Terry was born in Hartford, Connecticut on March 16, 1812 with strong New England roots. When Terry was young he moved to Michigan to study law, where he began his practice in Detroit (2.2). When the Civil War broke out Terry actively became interested and began to recruit soldiers in Michigan. Henry Dwight Terry became a Colonel of the Fifth Michigan Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. Colonel Terry ran a well-disciplined regiment, proving what a good military man he was. He led the Fifth Michigan through the Peninsula Campaign and was a key factor in preventing major losses during the Battle of Williamsburg. Soon after, Terry was promoted to Brigadier General and sent to Virginia. Terry commanded troops in a few more battles and directed enemy soldiers at a prison before eventually retiring. Terry is an important part of history in that he contributed to Union wins and Confederate losses or impasses. Terry is a hero who led his troops wisely on and off the battlefield for his country.

Fifth Michigan Infantry Regiment

Terry became interested in the military after the Civil War began. On June 10, 1861, Governor Blair of Michigan appointed Terry Colonel of the Fifth Michigan Infantry Regiment. The Fifth Michigan was within the Army of the Potomac. The Regiment was assembled on August 28, 1861 at Fort Wayne in Detroit. The officers arrived at the fort on June 21, 1861. The regiment was known as the “skeleton regiment” as it was being built out of nowhere. Terry was in charge of organizing the unit. He appointed men to their designated positions, like officers, quartermaster, sergeant major, and surgeon. Terry’s first command was vaccinating every enlisted man for diseases such as smallpox (9: pg.8).

Fort Wayne was a training camp located on the southern outskirts of Detroit, right on the Detroit River. This training facility was built from 1842-1861 after Congress ordered forts to be built from the eastern coast of the United States to Minnesota. This fort has a lot of rich history, such as Native American burial grounds on the site with remains dating over 900 years old, a village during the French and Indian War, and battles near the beginning of the War of 1812 (1.2).

While at Fort Wayne, The Detroit Daily Advertiser newspaper reported the regiment’s training progress.

“They, like all soldiers, desire to be as near the seat of war as possible… They are ready to go, and will be very glad to receive marching orders.” (9: pg.15)

Interestingly enough, the regiment was not prepared at all to go to war. The regiment continued to get new recruits who had to start the whole training from the beginning. Nearly none of the supplies had arrived at Fort Wayne, such as uniforms, bayonets, rifles, and other weapons. Because of al of this, marching and exercising were really the only ways for these men to train (2). This meant that the men had about one to two months, if that, of training, with most of that being without battlefield supplies. The Detroit Daily Advertiser reported everything that happened at the fort on nearly every day. On July 11, the local ladies from Trinity Church sewed 150 havelocks, a cloth that is sewn to a soldiers’ military cap, for the soldiers at Fort Wayne. Colonel Terry wrote a thank-you letter to the church ladies, which was printed the next day (3). August 21 came around and the regiment still did not have all of their equipment and uniforms to properly train. Colonel Terry ran a disciplined regiment in order to prepare his soldiers for battle (4). They began drills at 5:15 am, ate breakfast, participated in more drills, ate again at noon, did more drills into the evening, had one hour to eat before the nighttime march (9: pg.18). Terry did the best he could with the time he was given to get his men ready to be sent into the Peninsula campaign. Finally, on September 11, 1861 Colonel Terry wrote:

This Regiment will take up its line of march for Washington this Wednesday September 11th Evening at 7 o’clock, the Field and Staff together with Co.’s A, F, D, J, C, H, and the Baggage belonging to the same will embark on the Steamer Ocean under the Command of Lieut. Col Beach, Companies E, K, G, B Quarter Master, Sgt. and Commissary Sergeants together with the Baggage for the same will embark on the steamer May Queen under the command of Major Fairbanks. (4)

As the regiment prepared to be sent to Virginia, the regiment lined up for a final formation parade at Fort Wayne. A man only referred to by the Daily Advertiser ad “Mr. Backus,” read aloud a statement to the troops:

“You are from us, you are of us, bound to us by many strong ties that knit together the social compact and give to society itself its greatest side… This banner which I now unfurl to the breeze of freedom, take it and guard it, not only as friendship’s offering but as the ensign of truth and freedom. My friends, in the reception of this banner by you we feel more than compensated in the pledge that implies that you would never strike it…or will never surrender it to traitors.” (9: pg.21)

Colonel Terry accepted the banner from the man and said:

“God grant it may never trail in the dust.” (9: pg.21)

As part of the Army of the Potomac, Terry commanded the regiment through the Peninsula Campaign, a major Union operation in Virginia that planned an offensive on the Eastern Theater. The regiment travelled from Detroit, to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to Baltimore, Maryland, and then to Washington, D.C., which Colonel Terry referred to as the “Seat of War” (9: pg.23). Colonel Terry had a very rambunctious regiment, as he had to impose many rules and regulations on the men. He had to round up a couple dozen men after arriving at Washington because they were too excited to be there (5). Terry then put a limit on the soldiers’ leave of absence, giving officers three hours and enlisted men six. A prohibition on gambling was issued by Terry as well, as he felt that gambling could bring disorder and problems in a regiment. If the men broke this rule, they gave up a portion of their military payment or had an extra guard duty shift. Terry’s feisty regiment had another discipline rule that prohibited men and officers from firing weapons without proper authority after a soldier accidentally shot himself in the hand had to be amputated and another shot himself in the shoulder. In order to keep the men disciplined, Terry ordered drills and training pretty much all day long to keep the men busy.

However, the Army of the Potomac suffered heavy losses at the Battle of Williamsburg on May 5, 1862. Terry’s men fought at Williamsburg and in the surprise attack at the Battle of Seven Pines. The Fifth Michigan and its supporting regiments from New York were a big reason that the Battle of Williamsburg was not a serious setback for the Army of the Potomac. Terry ordered another charge that caused the Confederates to retreat, avoiding a bloodbath. General Sumner attempted to attack the backside of the Confederate army, but had to retreat. The Union Third Brigade, including the Fifth Michigan Regiment in the front, headed down Mill Road towards a battery of ten Union cannons captured by the Confederates. Colonel Terry ordered a charge after the firing began on the Confederates. This charge forced the Confederates to flee, yet still continued to fire at and kill those in the Union regiments. Terry then ordered a second charge, in hopes of preventing the slaughter of troops. The Confederates fled the battle, giving the Union back their weapons. These charges that Terry ordered and commanded with his Fifth Michigan Regiment were the reason that the Army of the Potomac did not suffer a slaughter in their first battle of the war. Without Terry’s thinking to charge the Confederates as the only way to prevent defeat, the Confederates may have defeated the Army of the Potomac to the point of extinction. The Fifth Michigan earned the nickname the “Fighting Fifth” (9: pg.76).

The Third Brigade commander, General Hiram Berry, “recognized the Fifth Michigan’s officers’ heroic leadership noting that Colonel Terry ‘was injured in the early part of the engagement by a spent ball, but continued in the battle to the end and conducted his men gallantly” (1.2: pg.39). The injury was easily treated and Terry continued to command. Terry offered words of encouragement to those who did fight and survive and condolences to those who lost their lives in the bloodbath at Williamsburg. The officers of other regiments were acknowledged for their leadership as well. The Union eventually withdrew from the peninsula after another defeat at the Seven Days Battle, a battle in which Terry’s troops did not fight.

“The dead sleep upon the field of our victory, and they sleep well. Their graves mark the spot where (beside the same breastworks) our Revolutionary fathers fought and fell before them, and though perhaps no report may be made of their devotion to the Union and the Constitution of the country, their surviving comrades will never forget them.” (7)

“They died where brave men ever die — at their post of duty.” (1.2: pg.47)

Brigadier General of Volunteers

A few weeks after the Peninsula Campaign ended in early July, Terry was promoted to Brigadier General of Volunteers when he was told to report at Fort Monroe in 1862 (8). Terry was sent to Suffolk, Virginia, where he commanded a brigade within the VII Corps. The men in his brigade were from Michigan, New York, and Pennsylvania. The Union ended up losing Suffolk to the Confederates in the early months of 1863. Shortly after losing Suffolk, in June Terry was sent to White House, Virginia to aid in the defense against General Robert E. Lee to cut off his communications line to Richmond. Lee was leading the Confederates to an invasion of Pennsylvania, better known as the Battle of Gettysburg. Terry was not directly involved in the Battle of Gettysburg, yet aided the Union in cutting communications so that the Confederate attack would be either lost or lessened. After a march to Baltimore Cross Roads near the Confederate capital, the IV Corps led by Major General Keyes, Major General Dix, and Brigadier General Terry retreated towards the White House the next day (1.2: pg.27-31).

Keyes and Dix were removed from their field commands due to the failed attack. Terry, however, was returned to command the Army of the Potomac, leading the VI Corps (1.2: pg.47). Although Terry was commanding during the failed attack, his performance was still strong enough to keep him his position as Brigadier General. With the VI Corps, near the end of 1863 Terry and his troops aided Major General Warren’s V Corps in the Battle of Mine Run. The battle resulted in an inconclusive victory for either side, as the Union did not complete a successful attack as Lee felt the Confederates did not have enough to counter attack (3.2).

End of Military Career

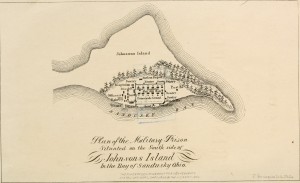

Terry was then sent to be the commander at Johnson’s Island Prison in Ohio near the start of 1864. At Johnson’s Island in Sandusky Bay near Lake Erie, Confederate officers who were captured were held until 1865 (6.2). The prison could hold nearly 3,000 prisoners. Terry was sent to guard the prison only for a few months. Terry surely had the discipline and control to be a prison guard from all of his past commanding experience. In May of that year, Terry’s troops returned to Virginia for the spring campaign (6.2).

Terry fought in every battle with purpose and might. He did not loosely command his troop, either, he disciplined for the good of his men to prepare them for war. Every soldier that he commanded respected him. Terry was highly respected by his peers and superiors as well, being promoted multiple times and expected to lead regiments well during a battle. Even when the commanders that fought along side Terry in the same battle were removed from their commands, Terry kept commanding the VI Corps of the Army of the Potomac because of his high level of experience and skill.

After returning to Virginia, Terry felt that he was no longer of value to the military and left. He had accomplished so much already in his military career, most notably his aid in the prevention of slaughter and complete defeat at the Battle of Williamsburg in 1862. There are no military records after Terry’s departure. Finally, on February 7, 1865 he resigned and moved to Washington D.C., where he returned to practicing law for a few years until his death (2.2). He died in Washington D.C. on June 22, 1869. He was buried in Clinton Grove Cemetery in Mt. Clemens, Michigan.

Primary Sources

- “Battle at Williamsburg: High Commendation of the Michigan Troops.” The Detroit Free Press (VOL. XXV), 24 May 1862.

- “Home Matters: The Fifth Regiment.” The Detroit Daily Advertiser, Aug. 20, 1861.

- “Camp of Instruction.” The Detroit Free Press, July 11, 1861.

- Order No. 19, Sept. 11, 1861, 5th Michigan Infantry Order Book.

- “The War: The Fifth Regiment.” The Detroit Free Press, Aug. 20, 1861.

- “Battle at Williamsburg: High Commendation of the Michigan Troops.” The Detroit Free Press, May 24, 1862.

- “The Michigan Fifth.” The Detroit Free Press, May 14, 1862.

- Record of Service of Michigan Volunteers, 5:133-34.

- Sebrell III, Thomas E. A Regimental History of the 5th Michigan Infantry Regiment From Its Formation Through the Seven Days Campaign. Blacksburg, VA, 12 May 2004.

Secondary Sources:

- Sebrell, Thomas E. (2009). “The ‘Fighting Fifth’: The Fifth Michigan Infantry Regiment in the Civil War’s Peninsula Campaign.” Michigan Historical Review2: 27-51.

- Finney, David and Judith Stermer (2015). Remembering Michigan’s Civil War Soldiers.Arcadia Publishing.

- Hepburn, Sharon A. Roger (2008). “The Journal of Southern History.” The Journal of Southern History2: 465-466.

- Warner, Ezra J. (2013). Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Louisiana State University Press.

- “Encyclopedia Of Detroit.” Detroit Historical Society – Where the Past Is Present.

- “The American Civil War.” Johnson’s Island Prisoner of War Camp, 2012.

- Henry Dwight Terry. Image. upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/15/H.D._Terry.jpg.

For Further Reading