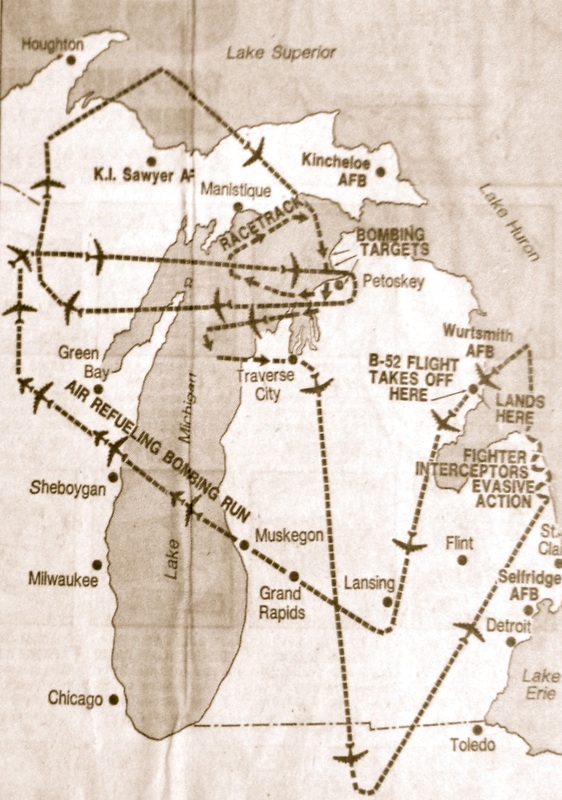

On January 7, 1971 at approximately 6:33 p.m. local time in the small town of Charlevoix, MI, residents of the community were startled by an explosion in the Little Traverse Bay. A Strategic Air Command B-52C was on a routine radar bomb scoring flight when it plummeted into the cold waters of Lake Michigan. What is more startling is that the massive aircraft was flying only at 700 feet when it crashed roughly 5 miles north of the Big Rock Point nuclear power plant. Even more astonishing, the B-52 was intending to fly directly over the nuclear power plant moments later.

Peaceful Use of Atomic Energy

During the Cold War, the buzz word “nuclear” was normally associated with the fact that the United States and Soviet Union were on the brink of nuclear war. Both sides would flex their nuclear might through the deterrent factor of being able to deliver a nuclear strike at moment’s notice. The Strategic Air Command (SAC) in the United States relied heavily on utilizing the B-52 heavy bomber as a mechanism to being able to deliver that nuclear strike to the Soviet Union.[11] Because of this, the B-52 became an iconic symbol across the nation that was associated with the word “nuclear”. Less well known to society were the undertakings of private energy companies exploring the use of nuclear power for commercial energy. Consumers Power was one such company with early interest in the endeavor. In 1959, they had their eyes set on the south shore of Little Traverse Bay in the small town of Charlevoix, MI.

The plant would be named Big Rock Point. Construction of the plant started on July 20, 1960 in front of a crowd of 250 spectators. The construction was backed by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) whom stated it “supports any business in the peaceful and constructive uses of atomic energy”.[2] The AEC was not aware at the time that roughly three years later, the “peaceful and constructive” use of atomic energy would be used to aid the training for the Strategic Air Command’s “peaceful” use of atomic energy. The SAC’s view on peaceful was the threat of being able to use atomic energy packaged into a droppable bomb from an aircraft. This will start to play out as the 1960’s advanced toward the 70’s. Government agencies aside, headlines circled the local news outlets with front page titles such as “Atomic Power Age Near for Northern Michigan” or “Michigan Goes Nuclear”.[2][3] Consumers Power’s president informed the public the “$28 million dollar plant should be finished in September 1962”. [2] Just missing the mark, 29 months later the plant was officially complete.

The early operation of the plant was intended for research and development to prove nuclear plants were economically feasible in producing electricity. It did just that and in 1965, using its 10 ton load of uranium and the 67 Megawatt General Electric boiling water reactor, the plant was producing electricity for the local communities. “Big Rock”, as the locals called it, became Michigan’s first commercial nuclear power plant, and only the nation’s fifth overall.[9] Little did the plant know at the time of its construction, it would also become the “target” of low flying SAC bombers as they simulated bomb drops to stay prepared in case they needed to go operational against the Soviet Union.

One Close Call Too Many

It is unknown whether the SAC brass were reading the headlines in July 1960 or an instance of pure coincidence occurred, but what is certain is that in 1963 the SAC moved a radar bomb scoring detachment from Ironwood, MI to a location 5 miles east of the newly constructed nuclear plant. These radar bomb scoring sites were used to evaluate the effectiveness of bomber crews by using radar pulses to simulate bomb drops. Maybe a lesson in leadership was learned from George S. Patton who once stated “you fight like you train” which later was adopted to “fight like you train, train like you fight”.{*} {^} What better way to train for nuclear war – in case it became the fight – than use targets you might actually engage. B-52 bombers could pretend to drop bombs on arbitrary locations, but why not a nuclear power plant that fictionally could be used to create the nuclear payload for a Soviet Union ICBM ready to launch against the U.S. Like war gaming, it is way more interesting the closer to reality the exercise is. Regardless of the reason for the move from Ironwood to Bay Shore (next to Charlevoix), the RBS site was operational in 1963 and conducted high and low level radar bomb scoring until its decommission.

Bombers that flew the simulated bombing missions flew at both high and low altitudes. The majority of the runs would be conducted at low level entry since Soviet air defenses performed exceptionally well at defending the high altitudes. The low level routes the aircraft flew became known as Oil Burners. Oil Burner 9 (OB-9) was the Northern Michigan route that included the Big Rock Point plant in its bombing corridor. Strategic Air Command bombers flew OB-9 constantly since the RBS site’s inception in 1963. In the very beginning, some local residents were startled by the “sonic booms” that were created from the supersonic aircraft that flew the route.[5] Eventually it became apparent that the sonic booms and bomber overflights were there to stay. Lt Col Joseph King, commanding officer of the local radar bomb scoring squadron, assured that to the public in several appearances with the press. Over time, the low and high flying aircraft, along with the occasional sonic boom, became natural to the surrounding communities and went unnoticed. It may have been swept under the rug in the local communities but Charlevoix’s nuclear power plant was following the flights very closely.

The plant would constantly express its concern of bombers flying low and so close to the plant. The plant was not the only entity concerned with it being in the bombing corridor, their insurance company was as well. In fact, they were so concerned that they raised the annual premium for the plant in December 1970. The timing couldn’t have been more ironic. On January 7, 1971 – less than a month after the insurance company raised the premium – a 450,000 lb. B-52C plunged into Little Traverse Bay only a few miles directly north of the nuclear power plant.[1] Following the crash, the bombing runs were in the spotlight for both the public and the Big Rock facility, which was nearly seconds away from becoming the crash site. (Interested in reading in depth about the crash? Check out the story here)

Finding another Route

Dating back to November 29, 1963, the Big Rock Point plant was concerned with the OB-9 route. One of the first letters from the Atomic Energy Commission’s Director of Regulation addressed this concern. The letter from Harold Price to the DOD’s Department of the Air Force identified “[…] the Strategic Air Command has been using the Big Rock Point Nuclear Power Plant at Charlevoix, Michigan as a target for practice bombing runs […]” [6] and expressed his desire reroute the flights. A reply from the Air Force assured them they would not fly directly over the plant.[7] The overflights still continued. The AEC and DOD remained in occasional contact about the overflights. One letter of correspondence provided insight into the OB-9 route. The Bay Shore RBS site provided data to the Big Rock Point plant superintendent which reported:

- 300 overflights per month at altitudes around 1900 feet

- 8 overflights per month at 500 feet

- OB-9 was a north to south path, a corridor approximately 8 miles wide with the center off-set about 100 yards from Big Rock Point.

The letter also presented the fact that the vice president of Consumers Power reached out to Michigan Congressman Gerald Ford on December 16, 1970. The vice president requested the assistance of Congressman Ford to stop the overflights, or at least limit the off-set to 12.5 miles, instead of 100 yards. The Congressman wrote an Air Force colonel on December 21. This is when the insurance premium increase was brought up as well. It was after the crash when discussions began to accelerate.

An Air Force spokesperson for the crash investigation team announced to the Petoskey News Review on January 14, 1971 that the practice bombing runs over Bay Shore were suspended. Turns out, we was referring to the low level flights, as high altitude flights continued. A response to a memo from February 1971 contained information stating that aircraft from Shaw Air Force Base, South Carolina, “apparently used the plant for a turning point at times” [6] at altitudes of 1000 to 2000 feet. Apparently some “medium-low” level flights didn’t stop either. As time went on, the Atomic Energy Commission and the Air Force were working on a compromise to the flight route. Between February and April, AEC and DOD officials met regularly to develop an alternate flight plan. An alternate route was proposed which routed the flights on a center line that was 5.5 miles east of the plant. The corridor would be 8 miles wide, meaning the aircraft could only come to within 1.5 miles of the plant. The AEC and Consumers Power were onboard with the decision under that stipulation that a risk analysis would be conducted. The Air Force did just that and determined that the probability that a B-52 would stray from its path and enter the 1.5 mile buffer was about one in a million. The analysis also provided that the probability of a B-52 crashing within that buffer around the plant to be less than 1.5 in 10 billion. These findings were provided to Consumers Power on May 19 that year in hopes to initiate training flights on the alternate route. After some further discussion the low level training flights resumed until 1984 when the RBS site was closed. The question still remains on how lucky the surrounding communities were on January 7, 1971.

“We think so, but this is speculation”

Concerned citizens immediately after the crash began begging the question of what if the nuclear plant was hit. All sorts of individuals jumped in on the actions. Several op-eds and editorials hit the local newspapers providing citizen input. Ralph Nader, a political activist wrote a letter to the AEC reflecting his feelings. Mr. Nader wrote comments such as “what is difficult to understand is why flights had not been suspended earlier” or “it is symptomatic of the federal bureaucracy that no action was taken on these requests until a plane actually crashed”.[12] He was most likely referring to the beginning requests to reroute OB-9. To deal with the concerned citizens that were worried about what if the plant was hit, the information center coordinator for Big Rock released a statement. He stated:

“The way it’s [the reactor] designed, it depends upon many factors. Some of the factors include the following: 1- The weight and velocity of the object hitting the plant. At this point no studies have been made concerning a B-52; 2- It would have to penetrate the sphere of the structure (steal shell, 130 feet in diameter); 3- The shell its self is operated at lower than atmospheric pressure. If it is penetrated, the flow is in, not out; 4- Once it’s pierced we don’t have a problem unless the protection for the reactor system steam lines is broken someplace; […]”. [1]

Following his statement he was asked if such a plane did strike the plant, could the plant sustain the hit. He responded with “we think so, but this is speculation”. [1] Of course, all that information eased the public until Cambridge scientists in July 1971 addressed concern that emergency shutdown mechanisms used in the nuclear power plants at the time would not work well enough to prevent catastrophe. In the event of a cooling system rupture, the scientists said that water in the primary cooling system would discharge and the reactor core would be left without cooling. Although it might not cause an explosion, it could release a “cloud of radioactivity”.[4] The Big Rock plant responded to the Cambridge scientists’ findings and denied that their cooling safeguards were inadequate. The plant leadership said they were confident their systems would work as designed and “provide the safety features in the event of a major accident”.[4]

Primary Sources:

- Jim Herman, “Call Off Bay Shore Bomb Runs,” Petoskey News Review (Charlevoix, MI), January 14, 1971, 1

- Kirk Schaller, “Atomic Power Age Near for Northern Michigan,” Petoskey News Review (Charlevoix, MI), July 21, 1960, 1

- Lulse Leismer, “Launch Major Construction Today at Big Rock Point,” Petoskey News Review (Charlevoix, MI), July 20, 1960, 1

- Unk, “Big Rock Denies Cooling Safeguards are Inadequate,” Petoskey News Review (Charlevoix, MI), July 27, 1971, 1

- Unk, “Explain Cause of Sonic Booms Heard in Petoskey,” Petoskey News Review (Charlevoix, MI), July 31, 1963, 1

- United States. Atomic Energy Commission. Memorandum Correspondence. Washington: U.S. G.P.O., 1970-1971

- United States. Department of Defense. Department of the Air Force. Memorandum Correspondence. Washington: U.S. G.P.O., 1970-1971

- United States. Department of Defense. Department of the Air Force. United States Air Force Accident Investigation Board Report T/N 54-2666. Washington: U.S. A.F.D.P.O., February 1971

Secondary Sources:

- Betsey Tompkins, “Big Rock Point: From groundbreaking to greenfield“, Nuclear News, November 2006, 36-43

- Greg Adamson, We All Live on Three Mile Island: The Case Against Nuclear Power (Atlanta: Pathfinder Press, 1981), 37

- Karen J. Weitze, Cold War Infrastructure For Strategic Air Command: The Bomber Mission, (Califronia: KEA Environmental, Inc, 1999), [Prepared for Air Combat Command Under Contract: DACA63-98-P-1354]

- Richard Wiles, “A Great Lakes Accident – Cold War Style”, Inland Seas 70, no. 1 [Provided Directly by Richard Wiles]

- World Nuclear Association, ” Fukushima Accident“, October 2017

For Further Reading:

- Wikipedia article: Big Rock Point Nuclear Power Plant

- MHUGL post about the crash: A Cold War Tragedy: B-52C Crash In January 1971

- Additional sources used for this research:

- Chicago Tribune – 1971

- The Detroit News – July 1963 – January 1971

- The Detroit Free Press – January 1971

- United States. Department of Defense. Department of the Air Force. Radar Bomb Scoring Historical Summary. Washington: U.S. G.P.O., 1983

A special thank you to Richard Wiles, who helped tremendously in uncovering the details of the incident, which lead to a deeper look into the story revolving around “Big Rock”