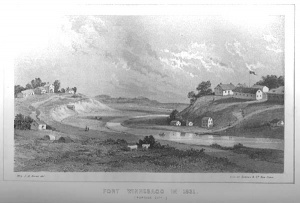

Fort Winnebago was a 19th-century fortification that was strategically placed due to its surrounding rivers in Wisconsin. During the time of being built, there were already two other forts, Howard and Crawford, in the Wisconsin region. Each of these forts were created to deal with conflicts regarding Native Americans. This area was significant because many settlers were in this area due to early mining, and the importance of controlling the portage which is a heavy connection between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. This fort was able to regulate transportation going through each important waterway.

Image from fortwiki.com

The fort received its name because of the Winnebago tribes that were established in the Wisconsin region during the fort’s creation. Winnebago is an Algonkian word that means “people of the dirty water” which is believed to describe the waters of Wisconsin’s Fox River. The fort was established to maintain peace with white settlers and the Winnebago tribe. This fort was constructed shortly after the Winnebago War of 1827. Today, they are known as the Ho-Chunk nation and most of their tribal members still live in the state of Wisconsin today.

Early Stages of Fort Winnebago

On the date of August 19, 1828, General Macomb, the current Secretary of War, issued Order 44. This order directed “The three companies of the first regiment of infantry, now at Fort Howard, to proceed forthwith under the command of Major Twiggs, of that regiment to the portage between the Fox and Ouisconsin rivers, there to select a position and established a military post.”(Macomb,1828)

As the order states, Major Twiggs was responsible for establishing a military post. David Emanuel Twiggs was born in Georgia in 1790. His father, John Twiggs was a leader of the Georgia Militia during the Revolutionary war. David Twiggs volunteered as a captain in the war of 1812 which later lead to a career in the military. He later became a major general for the Confederate States.

Image from Wikitree.com

Major Twiggs found the location of what would soon be the fort in September of 1828. The location selected for the site had already been occupied by a French trader, Francis LeRoi. The United States purchased the house from Leroi, to “use as medical officers’ quarters.” (C.F, 1975). Any time a fort was constructed during this era, it was the only area to receive medical assistance in the region, so it was common for many outsiders to get medical attention in the quarters.

After the purchase, Twiggs was aware of the local Winnebago Indians being “very much dissatisfied with the location of troops here,” (Twiggs, 1828) but he continued to establish a fort per the Secretary of Wars order. The construction of Fort Winnebago begun by the First Regiment of the United States infantry. By December of 1828, most of what was temporary buildings had been constructed to shelter the infantry prior to the construction of the fort being built properly. Operations for the fort to be built properly were soon in progress.

Image from Biography.com

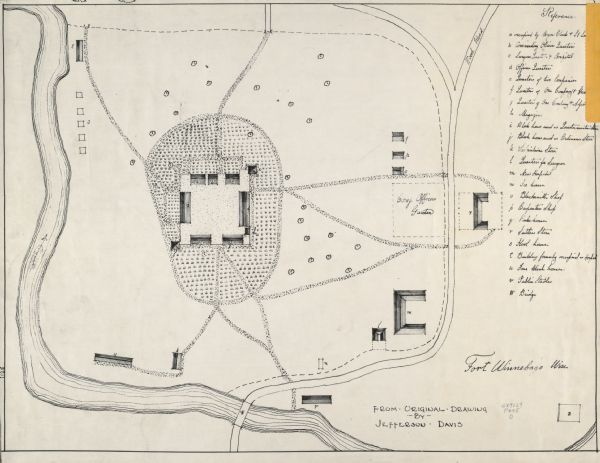

During the construction of this new fort, Lieutenant Jefferson Davis, a young man at the time, had experience with construction from a previous fortification, Fort Crawford where he oversaw the construction of a sawmill. On the Fort Winnebago project, he was assigned to oversee a party of soldiers to procure logs for the work of the fort. He and his men would travel away from the fort along the Yellow River, and they would collect pine logs for the construction of blockhouses, barracks, and stores. After obtaining the logs, they would be hauled across the portage with the help of others. His services on the Yellow River for Fort Winnebago made him respected among the other soldiers and ranks.

Jefferson Davis was born in Kentucky in 1808. He attended the United States Military Academy in 1824 and later graduated in 1828. After graduation, Lieutenant Davis was assigned to the first infantry regiment and initially stationed at fort Crawford and eventually became a lieutenant under the leadership of Twiggs. He later became the president of the Confederate States.

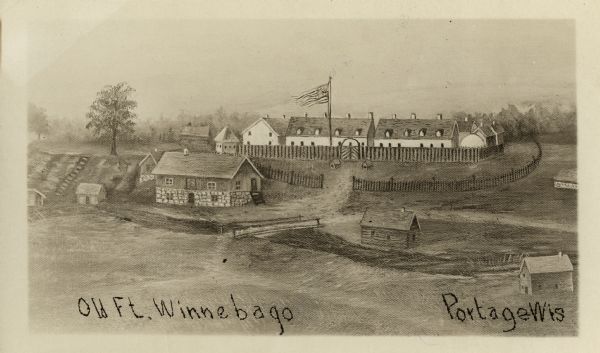

Life at Fort Winnebago

Image from Wisconsinhistory.org

Once the fort was fully established, it contained various applications and forms of entertainment. As stated by Andrew Jackson Turner, “Stables, hospitals, bakeries, blacksmith shops, commissary buildings, ice-cellars, laundries, bathhouses, etc., rapidly sprang into existence”. Among the community, the men were often fishing, hunting, and would spectate other surrounding habitats and land. While the soldiers were busy in the wilderness, the woman would often teach, clean, and other house duties.

They were also a welcoming community, Captain Marryat, an English officer who was traveling Wisconsin during the active Fort Winnebago, stayed in the community for several nights. “It [Fort Winnebago] is beautifully situated, and when the country fills up will become a place of importance. Most of the officers are married, and live a very quiet, and secluded, but not unpleasant life.” (Marryat, 1898).

There was also weddings, singing, theatricals, and other festivities that took place for entertainment. Among the soldiers, they would participate in drinking and gambling when they were able to. This lifestyle was common for 19th-century military men and their families in garrisons.

Fort Winnebago Personnel

Along with Lieutenant Davis, and Major Twiggs, there were many other ranks that were able to call Fort Winnebago their post. Two of these men were Lieutenant Horatio Phillips Van Cleve and Lieutenant Randolph B Marcy.

Horatio Phillips Van Cleve was a lieutenant stationed at Fort Winnebago. He graduated from the United States Military Academy and he was commissioned as a lieutenant of infantry in 1831. He met his wife, Charlotte Clark, the daughter of Major Nathan Clark, at Fort Winnebago. They ended up getting married in the fort in 1836. He later became a general of the Union Army.

Randolph B Marcy was a lieutenant stationed at Fort Winnebago. He graduated from the United States Military Academy and was assigned as a lieutenant in the infantry. Right away he saw combat in the Black Hawk War which was in the Wisconsin and Illinois region. He was eventually stationed to Fort Winnebago from 1837-1840. He later became chief of staff to his son in law George McClellan.

One of the Fort Winnebago’s early doctors was Dr. Lyman Foot, a surgeon, and physician. He grew up at many different military posts, and he was known for being social and professional.

Military Road

During the forts reign, soldiers were given duties such as road-making to construct a military road between Portage and Fond du Lac Wisconsin. The purpose of Military Road was to enable transportation of supplies from Fort Howard, to Fort Winnebago. It was completely funded on the government’s expense.

In 1835, Lewis Cass, the Secretary of War, ordered to construct the route. Those stationed at Winnebago had the responsibility to build the road from their post to the Fond du Lac river and bridge the streams. Whereas, those stationed at Fort Howard had the responsibility to link the route from their post to Fond du Lac.

The Military Road commissioners were Judge Dory and Lieutenant Alexander J. Center. They had already surveyed the route during 1831 and 1832. The road from Fort Winnebago to Fond du Lac was about sixty miles and would cost approximately $17,292 to construct (Cole, H.1925).

Fort Winnebago Cemetery Soldiers’ Lot

Image from findagrave.com

Within distance of Fort Winnebago, is the Fort Winnebago Cemetery Soldiers’ Lot. Burials in this cemetery started in 1835. According to the National Cemetery Administration, “The 2-acre site was designated as a soldiers’ lot in 1862”. This post cemetery was excluded from the public sale of Fort Winnebago in 1854, and the cemetery includes the dead from the Revolutionary war through World War 1. In order to be eligible for a burial, you must have been a member of the armed forces and meet active duty requirements. In 1924, the Daughters of the American Revolution installed a boulder monument with dedication to the unknown dead soldiers in the cemetery. It also marks the site of the surrender of Red Wing, the Winnebago tribe’s chief in 1827.

Later Years of Fort Winnebago

Image From Wisconsinhistory.org

Due to other wars emerging with Mexico, orders to evacuate the fort were given in 1845. The troops of fort Winnebago were sent to St. Louis to help with those stationed at Jefferson Barracks. After a majority of the troops and ranks left, the fort was left for Sergeant Van Camp to command, however, he died shortly after. Captain William Weir was appointed to fill his place. He remained in command of the low populated garrison until 1853. From Fort Winnebago’s early days, up until 1853, they managed to avoid any combat or military activity while being occupied. Since tensions with the local tribes had lowered, and most of the United States Military were fighting in other regions, the fort was sold. In September of 1853, then Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, a man who once served as a lieutenant in the fortification earlier in his career, sold the location.

Post Fort Winnebago

Years after being sold, a fire emerged in the privately-owned houses of what was then Fort Winnebago. “The greater portion of the buildings of old Fort Winnebago were destroyed by fire” (Chicago Daily Tribune, 1856). There were no reported deaths from the fire. Although the fort and its buildings were not being used by military personal, there was still families who lost properties.

Today, all that remains of the once 200 soldier occupied garrison is a historic house museum called Surgeons Quarters that officially opened in 1954. This was the original French trader building that was already established when the fort was being initially being built. It has been restored to its original form using archives, and there are tours given to those who are interested.

Image from Fortwiki.com

Primary Sources

- Maj. David E. Twiggs. David E. Twiggs to Morgan L. Martin, September 7, 1828.Letter. From The history of Fort Winnebago. Madison: Democrat Printing Company, State Printers. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov

- Fort Winnebago destroyed by fire. (1856, Apr 11). Chicago Daily Tribune (1847-1858) Retrieved from https://services.lib.mtu.edu

- Marryat, F. & State Historical Society Of Wisconsin. (1898) An English officer’s description of Wisconsin in. Madison: Democrat Printing Company, State Printers. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/

Secondary Sources

- Wisconsin Historical Society. Wisconsin Local History & Biography Articles; Portage Democrat; Portage, Wi; 3-28-1879; viewed online at https://www.wisconsinhistory.org on [10-13-2019]

- Church, C. F. (1975, Jul 13). Frontier days recalled in historic portage, wis. Chicago Tribune (1963-1996) Retrieved from https://services.lib.mtu.edu

- Turner, A. J. & State Historical Society Of Wisconsin. (1898) The history of Fort Winnebago. Madison: Democrat Printing Company, State Printers. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov

- National Cemetery Administration. (2015, April 21). VA.gov: Veterans Affairs. Retrieved from https://www.cem.va.gov

- Cole, H. (1925). The Old Military Road. The Wisconsin Magazine of History, 9(1), 47-62. Retrieved from www.jstor.org