The George Armstrong Custer Equestrian Monument was erected to commemorate Custer’s early life and his service during the Civil War. Custer’s rise through the ranks in the US Army during the Civil War was in part due to his charismatic attitude. In Monroe, where he grew up, and throughout his time at the West Point Military Academy, Custer’s pranks and boyish demeanor would develop him into an American military legend, even if the legend is somewhat controversial.

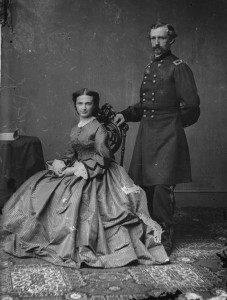

The Custer Equestrian Monument is currently located at the corner of Elm and North Monroe St. in Monroe, Michigan. The idea for the statue came from Custer’s wife, Elizabeth “Libby” Custer. Elizabeth Custer viewed her husband as a symbol of power, notably in a letter to Michigan Governor Fred Warner in request for the statue she states, “I have no voice in the selection of an artist and may not have, but what I can say to you is that I would feel very badly unless the statue was the work of a man, and one who has vigor and power to do a horse as well as a soldier” (Custer, 1907). In 1910, with “Libby” in attendance, the statue was unveiled as a monument to honor Custer as a hero during the Civil War. Monroe, Michigan served as an adopted home for Custer. Spending his childhood and early teens in Monroe would shape his decision to return to the small town after the Civil War. The statue was moved twice, first because it was a motor hazard and later due to public protests in accordance with the controversial history of Custer’s late life.

When George Armstrong Custer was 10 years old, he moved to Monroe, Michigan to stay with his half-sister Lydia and her husband David Reed. Monroe was a small town of only 4,000 inhabitants, but it was a change of scenery from Custer’s village home in Ohio. Custer now had two homes, in Monroe and his birthplace Ohio, and often traveled between the two during his childhood. Traveling provided the young Custer a diverse experience, something not many people could afford to do in the mid-1800s. “This (traveling) may have given him a feeling of superiority, a certain youthful maturity”. Indeed, Custer had created an inflated sense of self that would follow him throughout his life. Custer’s ambition was probably also so large because his father, Emanuel Custer, was a blacksmith who had enough to support his family, but not much more (Monaghan, 1971). Custer wanted more in his life, he wanted to be respected.

Custer in his childhood was known for his compulsive behavior and capacity to pull off elaborate schemes. One winter, Custer and his childhood friend Joe Dickenson were riding a carriage with a group of girls. Custer reminded Joe of another girl from a farm not far from them. Once the boys picked up the girl, there was no more room in the carriage. Custer’s friend Joe got the hook and ended up riding one of the horses while Custer stayed comfy with the girls. It was Custer’s plan all along (Monaghan, 1971). Custer was a creative thinker, and his pranks were an early indicator he had the capability to think outside the box. His childhood plan was working, with every prank his popularity grew, albeit sometimes notoriously. “While living in a small campus cottage at Hopedale he was attempting to get some sleep in the attic. When some noisy girl visitors below were slow to leave, Custer thrust his bare feet and legs through unclad. In those days of modesty that could have but one effect. The girls left” (Frost, 1964). Although the children of Monroe began to know Custer very well, he didn’t want to just be known as a prankster. He thought of careers that would give him the respect he believed he deserved.

Even as a child, Custer enjoyed reading military novels and set his ambitions to be a soldier (Griffith, 2013). As a student in Monroe, Custer used to smuggle a copy of Charles Lever’s military romance novel Charles O’Malley, the Irish Dragoon into class (Monaghan, 1971). Ironically, Custer’s life would play out as a near analogous military romance. Custer’s wife Elizabeth, “Libby”, described in her Journal during the Battle of Washita, “[I] often thought of the song: ‘The bold dragoon he has no care as he rides along with his uncombed hair’” (Custer, 1890).

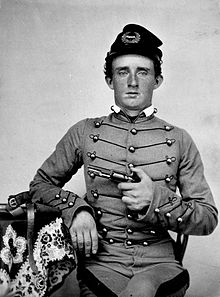

George didn’t just read military books, instead he decided to join the military by applying to the Military Academy at West Point. The story behind Custer’s admittance to West Point only furthers the notoriety of his devilish childhood. In his late teens, Custer fell in love with a girl named Mary Holland. Mary was the daughter of a well-off farmer who happened to have a connection with Custer’s congressman John Bingham. To get into West Point, each candidate requires a recommendation from a congressman. As Custer’s love for Mary grew, he came up with the idea of marrying the young girl. However, Mary’s father had other ideas and would not allow a boy whose family had different political ideologies to become a part of his family. Maliciously, Mr. Holland believed if Custer went to West Point, he would not be allowed to marry during his education per West Point rules. Mary’s father used his connection with Congressman Bingham to give Custer the nomination, and in turn be unable to marry his daughter for five years (Monaghan, 1971). Mr. Holland’s plan worked, Custer went to West Point and later married another woman.

George Armstrong Custer’s devilish behavior would follow him into West Point. Out of 34 cadets in his class, Custer graduated 34th (Griffith, 2013). Despite his graduation, Custer’s behavior nearly caused him to get kicked out of the Army before he ever got in. Just prior to Custer’s appointment to a unit, while still at West Point, Custer was given the duty of officer of the guard. During his watch, two cadets began a skirmish in the courtyard and soon a crowd was gathering. Custer’s job was to stop the skirmish and dismiss the crowd, however, Custer had other ideas. He moved his way to the front of the dispute and loudly proclaimed, “Stand back boys, let’s have a fair fight” (Griffith, 2013). It just so happened, at the time of Custer’s outburst, two officers were walking up to the dispute. They apprehended Custer and reported to Washington he was the cadet responsible for the grounds that night. Under the military code of justice, Custer was sent to court and pleaded guilty to the matter. Custer was detained while the cadets of his class went to Washington for duty. In true Custer fashion his time in detention was not long. His popularity again got him out of a mess and his friends got a release form from the Adjutant General to release him and report for duty (Griffith, 2013).

Despite his boyish behavior, as if he never left Monroe, Custer would prove to be one of the Union Army’s greatest commanders. Custer’s outlandish behavior and risk taking would ultimately prove to be one of his greatest strengths as a military commander. In one instance, Custer decided to ride his horse into a river to determine if it was passable by his men. Unfortunately for his soldiers, Custer wasn’t always so considerate. George Custer (1876) writes during the Battle of Washita, “no halt was made during the day either for rest or refreshment”. His lead-from-the-front style, despite its inherent risks, made him distinguishable to high-ranking officers. His fearless and aggressive attitude helped him survive and win in some of the Civil War’s most notable battles including: The First Battle of Bull Run, Antietam, Gettysburg, The Siege of Petersburg, and the Appomattox Campaign. At the age of 23, Custer’s notorious behavior helped him become one of the youngest Union Generals.

Sitting atop a giant bronze horse in Monroe, Michigan, George Armstrong Custer’s officer’s saber and flowing locks of hair symbolize a warrior and a hero. Monroe residents have long hailed Custer as a powerful symbol. In a letter to Elizabeth Custer from her father he writes, “No man [George Custer] could be made a general at 23 without influences unless there was something in him as a man and soldier” (Bacon, 1863). The city of Monroe has since chosen to honor Custer for his youthful success and victory in the Civil War. The equestrian memorial stands as a reminder that the boyish behavior of the Monroe resident would shape the actions of the great Civil War Commander.

Primary Sources:

1. Custer, Elizabeth (1907). Letter from Elizabeth Custer to Michigan Governor Fred Warner. August 8, 1907.

2. Custer, Elizabeth (1890). Following the Guidon. New York.

3. Custer, G. A. (1876). My life on the Plains; or, Personal experiences with Indians. New York: Sheldon.

4. Bacon, Daniel (1863). Letter from Daniel Bacon to Elizabeth Bacon. July 14, 1863.

Secondary Sources:

1. Monaghan, James (1971). Custer: The Life of George Armstrong Custer. Nebraska.

2. Griffith, Patrick (2013). Early Life of Custer. New York.

3. Detroit 1701.org (2010). George Armstrong Custer Equestrian Monument. George Custer Equestrian Monument.

4. Wert, Jeffry (2015). Custer: The Controversial Life of George Armstrong Custer. New York.

5. Frost, L. (1964). The Custer Album: A Pictorial Biography of General George A. Custer. Seattle: Superior Publishing Company.

For Further Reading: