The Cold War period following WWII had the entire country on edge at the idea of full-on nuclear war. Strategically speaking, concern of attack would be on military installments, industrial areas, and major urban centers. But in a small area in the Hiawatha National Forest about 24 miles west-southwest of Sault Ste. Marie, Raco Army Airfield stood as a defense against possible attack from the USSR. This location could protect all of Michigan, parts of surrounding states, and even into Canada. Armed with over two dozen interceptor missiles, Raco stood as one of multiple defenses from enemy bombers or other aircraft carrying conventional or nuclear payloads. Although it is named Raco Airfield, it is geographically separate from the small community of Raco, MI which lies 4 miles to the northeast along M-28.

Background of the Airfield

Built in 1940 on a previous civilian landing area, Raco AAF was used by the US Army until 1957. During WWII, the airfield mainly served as a refueling stop but could also be a supplementary site to Fort Brady to defend the Soo Locks. Following the war, the Army closed and then reopened the airfield to place multiple 75mm Skysweeper anti-aircraft guns whose circular platforms can be seen just southwest of the runways (Freeman 2016). With an effective range of only 4 miles and a maximum range of 8 miles, the guns would only have been used when defending the airfield itself if not possibly being able to engage hostile aircraft that passed close by. The airfield was closed in 1957 as the Skysweeper fell out of service to the Nike missile system and other long range surface-to-air (SAM) interceptor systems.

The BOMBARC System

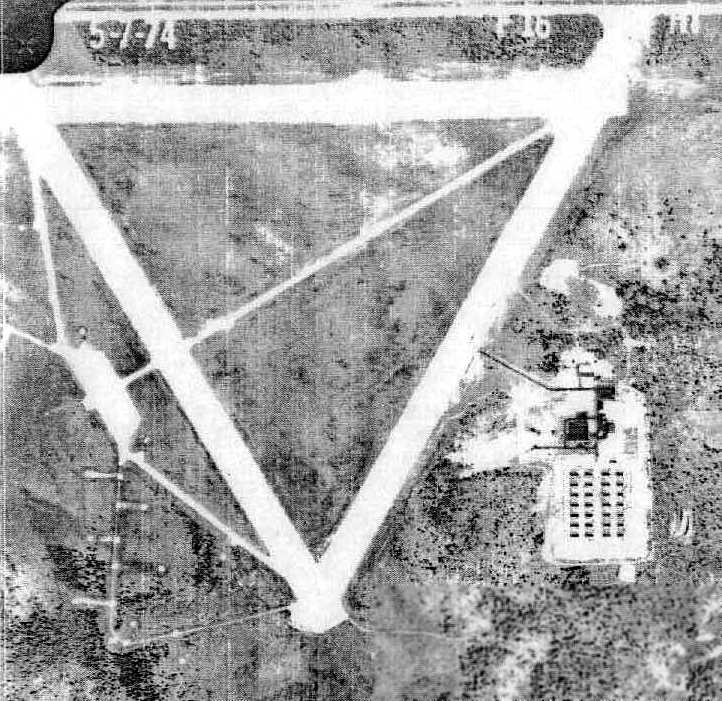

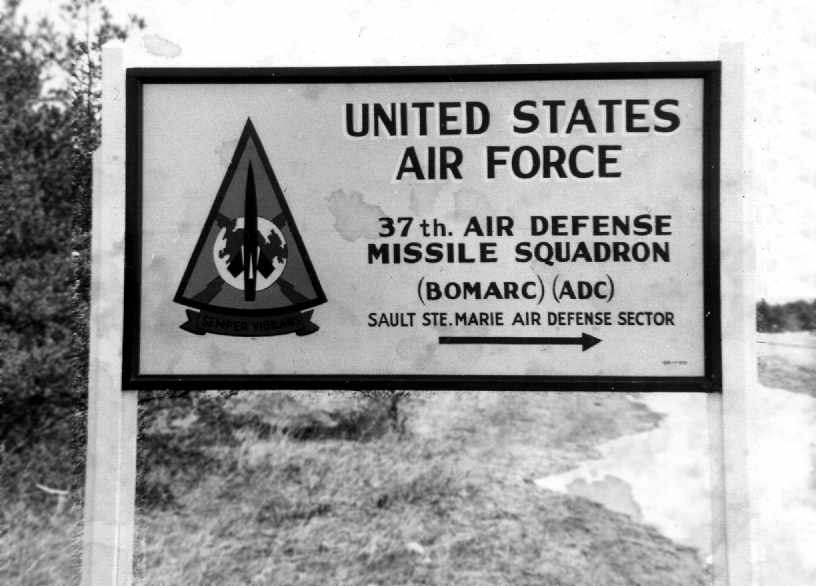

The BOMBARC program was started in 1949 in the research phase, and over the next several years had developed a long range missile, called XB-99 during the prototype phase. Three years later, the first prototype, an IM-99A predecessor, was unsuccessfully launched from Florida but by 1957 Boeing had accepted a contract. In 1958, former Raco AAF was being considered for a BOMBARC site. By this time, the IM-99A was deployed to multiple sites in the US. In 1961, Major General James C. Jensen, commander of the 30th Air Division, had accepted BOMBARC to Raco, and the missiles were manned 24/7 by the 37th Air Defense Missile Squadron (Raco 1961). During the Air Force occupation of the airfield it was also known as Kincheloe AFB BOMBARC site. Southeast of the triangular runways the Air Force constructed a BOMBARC missile site which housed 28 Boeing CIM-10 BOMBARC (also known as IM-99) surface-to-air missiles. Raco was one of the sites to receive IM-99B missiles installed as opposed those locations which had their missiles upgraded. Many of the old missiles were converted to supersonic targets used for weapons testing (National 2015).

At the time of construction of the site, Boeing had updated the missile system from the A version to the B version. The key difference was the type of fuel used. Liquid fuel in the IM-99A boosters was less efficient and posed a greater threat when launching and during maintenance. This was because the liquid fuel had to be stored separate from the missiles due to its corrosiveness, which added nearly two minutes to the launch time. The boosters were switched to a solid fuel which added both safety and greater thrust while increasing range, altitude, and speed. The IM-99B version of these missiles had a range of over 400 miles and were designed to eliminate hostile aircraft with either conventional or nuclear-tipped warheads. The Canadian Prime Minister, John Diefenbaker, had chosen to forgo designing a new missile system and simply rely on the BOMBARC system for protection from hostile bombers or other airctaft (“Guided Missile” 1958). Coverage is further increased with the distribution of these missile sites. Six locations were spread out over most of the Midwest and upper East Coast area, as well as two locations in Canada operated by the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). These locations would be able to protect most of the nation’s industrial cities and populated areas.

The CIM-10 weapon system relied on SAGE (semi-automatic ground environment) to guide the missile towards the target until about nine miles away when the primary tracking system could lock on and automatically detonate the warhead (Boeing n.d.). This was effective with a large blast radius; the missile could take out multiple aircraft if they were close enough in proximity to each other. SAGE was developed during World War Two for use with pilotless aircraft, but was revived as a means to control missiles using analog computers.

Who Was in Charge of BOMBARC at Raco?

The base was operated by the 37th Air Defense Missile Squadron (ADMS) from their activation on 1 March 1960 to their inactivation on 31 July 1972. The squadron was responsible for deployment of the missile if a threat arises, as well as maintaining the missiles and the silos they occupied. While they maintained the Raco site, they were technically stationed out of Kincheloe AFB in Kinross, MI. There were no missiles fired at threats from the location during the time they were there. However, the 37th ADMS did travel to test facilities for annual missile tests in Florida. The 37th ADMS consisted of weapons technicians of top caliber. According to a 1968 article from the Chieftain, Kincheloe’s unofficial newspaper, the unit won the Air Force Outstanding Unit Award for “maintaining an outstanding operation readiness status between the period of Aug. 30, 1965, and March 3, 1967” (“AF Names 37th” 1968). During their time at Kincheloe/Raco, the unit also received individual Top Missile Man of the Quarter honors from the NCO council at Kincheloe. The Raco BOMBARC site held anywhere between 25 and 40 personnel on duty with the rest of the squadron residing at Kincheloe AFB.

While the 37th ADMS had a very serious job, John Frye describes some of the activities the airmen would do to pass the time, “‘I spent many weekends on standby duty out there, and would ride a bicycle around the runways and hike in the area” (Freeman 2016). Frye was stationed at Kincheloe/Raco from 1962 to 1965 as a missile mechanic with the 37th ADMS. He also remembers the various buildings and sights during his time there. “We followed the old runway down to the chow hall and there was a Quonset hut housing a fire engine with storage and the chow hall just beyond, both built on the runway” (Freeman 2016).

Decline of Raco and BOMBARC

As the threat of bombings from bombers lessened, the need for the airfield and BOMBARC site was beginning to ramp down. As stated on Boeing’s website, “Bomarc was a successful program that met all of its original objectives, but the nature of the nuclear threat changed from primarily bombers to ballistic missiles” (Boeing n.d.). Congress declared the need for programs like BOMBARC (those which fell into the “continental U.S. air defense missile systems” category), to be no longer necessary in 1970. By 1972, the plans to shut down both facilities were in effect. The BOMBARC site at Raco was officially shut down on 31 July 1972. In the years following, the buildings and equipment that supplemented the base were removed and the land sold. As John Frye recalled “‘In 2001 the concrete base for the finger gates was still there, but everything else was gone with just some rubble’” (Freeman 2016). It is now home to Smithers Rapra winter testing facility for vehicle performance.

Conclusion

The BOMBARC system began as a large step towards a preventative missile defense system as a rising threat came from the USSR and their nuclear capabilities. During the time as Raco AAF, the site provided strategic placement of US Army and US Air Force personnel and equipment, mainly the 28 IM-99B/CIM-10 missiles. The 37th Air Defense Missile Squadron diligently maintained readiness in the event of a threat, but luckily the need for action was never realized. However, the 37th ADMS maintained excellence and earned praise and awards for such. But like all technological advances, a newer, more advanced system (in this case the Nike missile system) took over and made the BOMBARC system obsolete.

CIM-10 BOMBARC missile raised into firing position in silo (from airfields-freeman.com)

Primary Sources:

- “37th ADMS Missile Team Launches The BOMBARC.” Chieftain (Kinross), September 26, 1967. Print.

- “AF Names 37th ADMS As Top Unit.” Chieftain (Kinross), March 5, 1968. Print.

- “Bomarc, Michigan Inspired Missile, Now Operational At Raco Site.” The Evening News (Sault Ste. Marie), June 2, 1961. Print.

- “Guided Missile Considered For Operation At Kinross.” The Evening News (Sault Ste. Marie), October 30, 1958. Print.

- “Raco Bombarc Base Accepted By Air Force.” The Evening News (Sault Ste. Marie), June 1, 1961. Print.

Secondary Sources:

- “Boeing.” Boeing: Historical Snapshot: Bomarc Missile. Accessed November 17, 2016.

- “BOMARC.” BOMARC Site Locations. Accessed November 17, 2016.

- Freeman, Paul. “Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Northern Michigan.” Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Northern Michigan. February 24, 2016.

- “National Museum of the US Air Force™.” Boeing CIM-10 Bomarc National Museum of the US Air Force™ Display. June 4, 2015. Accessed November 18, 2016.