Modern civilization had to have come from somewhere. In Michigan’s case, modern civilization started with the French exploring New France. From there it evolved into forts and trading posts scattered throughout the state. Although there were many forts much bigger and more action packed, Fort Miami is just as important because it started it all as Michigan’s first fort.

Every story consists of the three same components: a beginning, a middle, and an end. In Fort Miamis case, the story starts out with a French explorer in the Midwest. From there, it moves on to the Potawatomi Indians. Finally, the story finishes with American fur trader, William Burnett.

The Beginning

When thinking about the migration patterns of the United States of America, settlements started on the East Coast and worked their way westward. In Fort Miami’s case, it was located on the western part of the Michigan territory. Why was the fort created in the southwestern region of the area rather than the eastern region? This is because of the story of the French explorer and fur trader Rene-Robert Cavelier Sieur de La Salle.

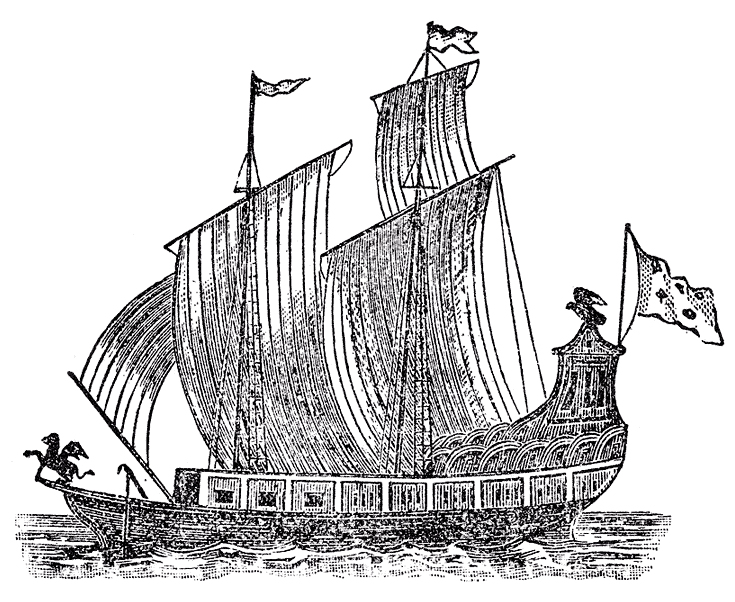

Robert Myers, author of “Greetings from St. Joseph,” describes that La Salle was born in 1643 in Rouen, France. After moving to New France in 1665, La Salle focused on exploring and fur trading. His mission from Louis XIV, was to explore the Mississippi, and to find a navigable route to the Pacific Ocean. In the spring of 1679, La Salle built a shipyard near Niagara Falls and constructed the Griffon. The Griffon was the first sailing vessel on the Great Lakes. La Salle’s vision for the Griffon was to have it be a floating trading post to trade goods with western Indians and reach locations throughout the Great Lake region faster. [2]

After sailing across the Great Lakes, La Salle sent the Griffon back to Niagara while him and his men stayed at the mouth of the Miamis River (now the St. Joseph River), named after the Miami Indian tribe that lived nearby, on November 1, 1679. [4] To keep his men from deserting, La Salle had them build a fort, Fort Miami. In Robert Myers’s book, Father Hennepin, a man who was with La Salle, recorded that the fort was

“pretty high and steep, of a Triangular Form, defended on two sides by a deep ditch, which the fall of the waters had made… we began to build a Redoubt of forty Foot long, and eighty board, with a great square pieces of Timber laid one-upon the other; and prepar’d a great Number of Stakes of about twenty five Foot long, to drive into the Ground, to make our Fort the more unaccessible on the River side.”[2]

In “History of the Great Lakes. Volume 1” by J. B. Mansfield, during the construction of Fort Miami, La Salle waited for the Griffon to return, which had recently set sail to Niagara in September of 1679. It never returned and in January, La Salle gave up hope. [5] Winter at Fort Miami would have been harsh, so on December 3, La Salle and his men set out on the Miamis River in hopes of completing his mission by finding a way to the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. [2]

On November 4, 1680, La Salle returned to Fort Miami only to discover that it had been burned down. La Salle continued his explorations of the midwest while his men were ordered to rebuild the fort. When La Salle returned to the fort on January 26, 1681, the fort had been rebuilt. There, La Salle stayed at the fort for the remainder of winter while waiting for the rest of expedition to return. Finally, in December 1681, the expedition reached Fort Miami. La Salle and his men left Fort Miami and never returned again. The Fort started to fall apart, and by 1689, there was nothing left of it. [2]

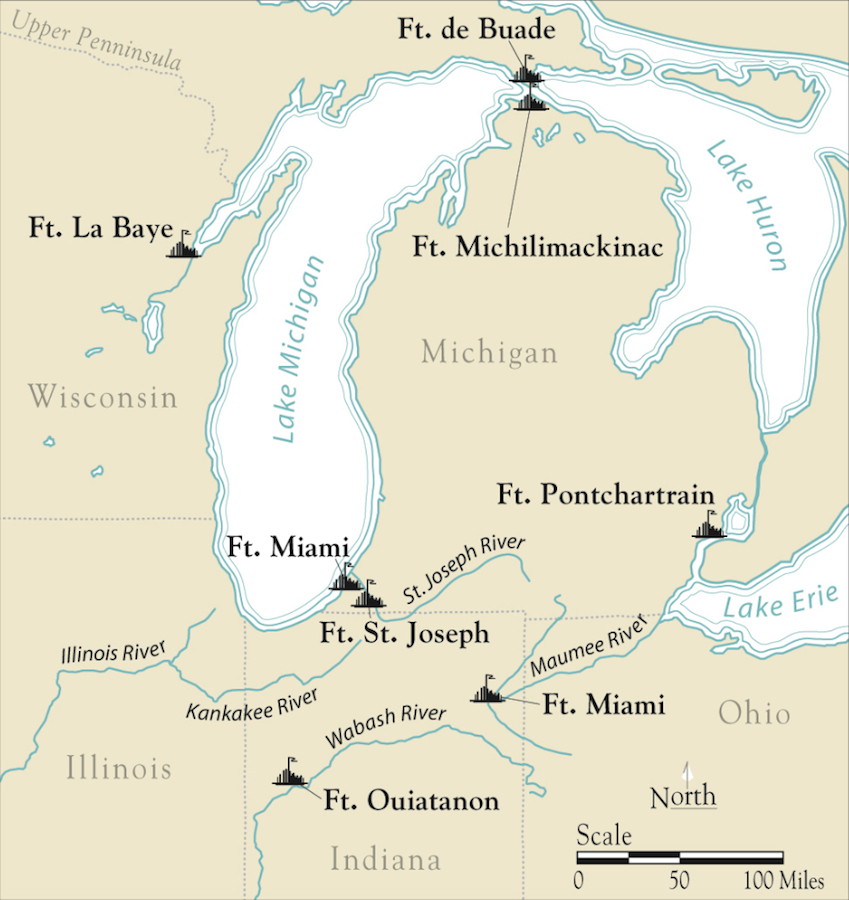

Although the first chapter of Fort Miami did not last very long, La Salle’s work in opening the upper Great Lakes and Illinois regions helped extend the scope of New France. Fort Miami also gave birth to two other forts that lasted longer and that saw more action in their lifetime, but in the end, saw the same fate. These two forts were Fort St. Joseph (present day Niles, Michigan) which played a role in Pontiac’s Rebellion, and Fort Checagou (present day Chicago, Illinois) which became a trading post of a later fur trader. [4]

The Middle

The story continues with the inhabitants of the Potawatomi Indians. The Potawatomi Indians’ story begins with the tribe living along the shores of eastern Lake Michigan. “Potawatomi Indian History” by Sussex-Lisbon Area Historical Society Inc., explains that in 1668, the tribes lived in villages that consisted of over 300 miles along the shore. The Potawatomi legend is that they are the “guardians of sacred fire.” By this legend, the Potawatomi believed that they were the chosen people, making them a leading tribe above all others. With these beliefs in mind, the Potawatomi battled their way from Wisconsin to Illinois and Indiana. Finally, the Potawatomi made their way to southwest Michigan, annexed it, and held all of the new gained territory. Because of this, the Potawatomi were one of the most powerful tribes in the Midwest. [3] For a long time, the Potawatomi held their power.

During the time the Potawatomi were invading and taking over tribes along Lake Michigan, La Salle had been just abandoned Fort Miami. This was sometime between 1680 and 1690. Once the Potawatomi entered southwest Michigan, they attacked and conquered the Miami Indians. The Potawatomi forced the Miami out of their homeland to be settled in Wabash while the Potawatomi took over southwest Michigan. The Potawatomi village was stationed near the mouth of the St. Joseph river, where the abandoned fort Miami used to be. It is documented that the village was still present in 1734. By then, the St. Joseph village itself consisted of approximately 100 warriors. Because of their legend about the “sacred fire”, the warriors declared themselves as the “governor’s eldest sons.” [3]

Not only were the Potawatomi excellent warriors, but they were also excellent in hunting, fishing, farming, and fur trading. All of these factors combined, made the Potawatomi the most powerful tribe in the midwest. Eventually, the Potawatomi migrated up the St. Joseph River, and participated in Pontiac’s Rebellion at Fort Detroit against the British and the battle of Fort Meigs in Perrysburg Ohio against the Americans. [3] Although the Potawatomi fought with the British, they were also betrayed by them, making their main ally the French. Through all of this, the Potawatomi stayed prominent in southwest Michigan by Fort Miami.

As the Potawatomi chapter comes to a close, it opens a new chapter about a fur trader in the same region. What links these two chapters together is the relationship between the Potawatomi tribe and the fur trader William Burnett.

The End

In the late 18th century, there was an increase in fur trade competition between American and British traders. Along with this competition, there was an increase in pressure to have the Indians move westward. [2] At this time, the British controlled the fur trade, even though it was slowly decreasing. But, even though the trade was controlled by the British, that did not stop Americans and the French from trading in the southwest Michigan region. The most successful trader was an American named William Burnett. [2]

In Elaine Thomopoulos’s book, “Images of America: St. Joseph and Benton Harbor,” William Burnett was the first white settler in the Fort Miami region. Burnett arrived sometime between 1775 and 1782. [6] Originally from New Jersey, Burnett was a fur trader who decided to trade in the southwestern Michigan region. His trading post was at the mouth of and along the St. Joseph River. In Robert Myers’s book, The post consisted of “his house, a barn, storehouses, a blacksmith shop and bakery.” [2] Not only did he sell fur, but also apples, quince, peaches, cherries, corn, cabbage and turnips. He also trapped around the region. His post became so successful that by 1798, he had opened another trading post in Chicago, Illinois. By the end of his days, Burnett’s business was known throughout the St. Joseph region, Kan Kan Kee, Kalamazoo, Chicago and other regions of Illinois and Wabash because of his relationship with the Indians. [1]

Burnett can credit his success with the marriage to his wife, Kaukema Nanaquiba Burnett, in 1782. Kaukema was a member of the Potawatomi Indian tribe. Not only was she a part of the tribe, but she was the daughter of the chief of the Potawatomi tribe. It is said that he married her because of “her beauty and for his protection.” [1] Together, Burnett and Kaukema, had seven children: James, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, John, Rebecca and Nancy. Kaukema also had two children before marrying Burnett: Lewis and Mary Ann. Both ended up being adopted by Burnett. [1]

Being such a successful businessman and fur trader, Burnett kept contact with many people throughout the region, along with other businessmen from Detroit and Montreal. Even though he was a businessman, Burnett was close to the Potawatomi and cared about them. His nickname was “The Trader” and was known by the Potawatomi as “Waub-Zee” or “White Swan”. [1] In “William Burnett ‘The Trader’ (Waus-Zee or White Swan)” , one letter was sent to Mr. WM Hands by Burnett, showing his care towards the Indians.

St. Josephs, April 11, 1791

I am at present moving down to lake; fear of any accident, as the Indians report that the Americans are coming again against them. If you have any newspapers or magazines by you send me some, if you can spare any. I hope there is a good prospect of the sale of peltries. No packs here this year. I am sincerely yours,

WM Burnett

Mr. WM Hands,

Detroit

Give the young lads some Bisquet for their voyage

Fur trading in the southwest Michigan region was tough. The field was risky and often ended in bankruptcy. In Robert Myers’s book, Burnett wrote in 1790 that a french trader, Antoine Le Clere, who had a post near Burnett’s,

“He has but little Goods as he has given the most he had last fall upon credit to the Indians and no likelihood of his being paid, as the Indians will make but a very poor hunt this year and also my being so near him so that he will not make both ends meet, I believe.”[2]

But Burnett also had trouble with his business. One time, Burnett was threatened by merchants in Detroit for having a long overdue debt. If Burnett could not pay his debts, his cattle would be confiscated in order to balance out the debt. Burnett’s response to this was that since he would not pay and that because the law in America was “dictated from principles of humanity” he was certain to come off on “easy terms.” [2] Another problem was how slow the region was in the winter. In the winter of 1787, the market was so slow that Burnett had almost nothing to do, and in 1790, he reported that most of the trading season was missed because he was looking for goods. [2]

Along with the slow winters, it was also very expensive to have goods shipped out for trading. At the time, the most efficient way to ship goods was on the water. But accidents happen. Even when the goods arrived, they had to have a good quality to make the Indians happy in order to have them as a trading partner in the competitive southwestern Michigan region. Because Burnett was such a good businessman, he kept up with his partners and kept them in order. Another letter was sent to Mr. G Ed’rd Young about the condition of the received goods in “William Burnett ‘The Trader’ (Waus-Zee or White Swan).”

Mr. G. ER’RD YOUNG,

Michilmakina.

ST. JOSEPHS, MARCH 25, 1794

Gents: I received your letters, with invoice and other paper, etc., the 27th of December last. But I am very sorry to inform you that I received all the goods in very bad order; all damaged, and some entirely lost. The vessel, by misconduct of the master, was drove on shore on the point of Mosquigon River. When the vessel struck she filled full of water, and the goods remained ten days after in the hold, from which you must judge in what situation the goods must have been. In the goods arriving so late, left it entirely out of my power to send out; will, therefore, have ⅔ of my goods remaining on hand, the best part of which much damaged. As I do not know rightly what time I will go to Michilmakina this spring, I have enclosed you two notes, which you will endeavor to get paid. You will remember that I left one with Mr. Pothier last fall belonging to Reaume, which he is to pay on his arrival, answered by him for Caltos, which last you have his note here for the balance of what he owes me. I am surprised I received no letter from Mr. Young, since he went down to Montreal, with respect to my sale of my peltries.

The bearer of this letter is the Reverend Mr. Ledrue, missioner, formerly at the Illinois. He wintered here with me, and bed you will assist him he gets settled at Makina, which I believe intends to do if there is good business for his trade.

I am, dear sir,

Your humble servant,

WM. BURNETT

Even though there were many difficulties that Burnett faced, the greatest difficulty was that he was American and an independent agent. The problem with being an American was that the trade market was mostly controlled by the British. This meant that Burnett was often harassed by the other British traders. This was done by the British merchants accusing Burnett of actions and crimes that he had not committed. The worst that the British ever did to Burnett was stating that he accepted a “wampum belt from a visiting American Indian agent, and of inciting sedition among the Indians.” [4] Although Burnett was innocent, he was found guilty and was taken prisoner at Montreal. Eventually he made it back to his trading post where he most likely died in 1813 or 1814. [2] After Burnett’s death, his trading post was taken over by his son James.

As the story of Fort Miami comes to a close, the region and the memories live on. The city of St. Joseph is now located at the site of Fort Miami. It started out as a village in 1834 and upgraded to a city in 1891 [6]. The city remembers its past and has sites set up around the city of historical markers. St. Joseph knows the significance of its history. St. Joseph reminds everyone that they are sitting on the start of Michigan as the site of Michigan’s first fort.

Primary Sources

- “William Burnett ‘The Trader’ (Waub-Zee or White Swan).“

- Myers, Robert (2008). “Greetings from St. Joseph.”

- (2002-2016). “Potawatomi Indian History,” Sussex-Lisob Area Historical Study, Inc.

Secondary Sources

4. Quaife, M.M (1914). “Making the Site of Old Fort St. Joseph,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908-1980) 6.4: 490-491

5. Mansfield, J. B.“History of the Great Lakes. Volume 1” Chicago: J. H. Beers & Co. (1899)

6. Thomopoulos, Elaine (2003). “Images of America: St. Joseph and Benton Harbor.”

For Further Reading

- Southwest Michigan Directory (2002-2017)”The History of Berrien County, Michigan,” Southwest Michigan Business and Tourism Directory.

- Smith, Mark A. (May, 7 2008) “The Story of the Burnetts and their culvert.” Pharos-Tribune.

- Glenn, Elizabeth and Rafert, Stewart (2009).”The Native Americans.” Indiana Historical Society Press