From 15 April to 31 October 1980, hordes of refugees crossed the US border by sea, these were called “The Freedom Flotilla.” What many Midwesterners thought would never affect them became a stark reality for those in Monroe Country, Wisconsin. Approximately 15,000 Cuban refugees flooded Fort McCoy, an active duty Army Installation as a part of the greater resettlement effort. This marked the beginning of an event which would change the perception of the United States military for the rest of time. The United States military was now taking on a humanitarian effort, at a scale it had never seen; converting a peacetime facility, which was being used regularly for training both active duty military, national guardsmen, and US Army reservists, into a haven for people abandoned by their own country.

Cubans had fled at the earliest chance an oppressive regime at home, to enter the United States in search of a home, where the violence and injustices of their past would not continue to haunt them. What they found, was largely the opposite. For the few that made it through without issue it was a path to freedom and sponsorship in America, but for those who took more than just a short time to pass through the system, they were exposed to rape, homosexual assaults, riots, and in few instances- murder, [9, p.160] The Cuban resettlement, bringing the lost individuals to their new homes across America.

In May 1980, US Army Forces Command began an inquiry, to determine the capacity of Fort McCoy to house and support incoming refugees in support of the Cuban Refugee Operation. Upon initial negative response about the capacity to house the necessary 15,000 incoming refugees, the order was given to immediately construct the necessary facilities by the end of the month of May. With 14 days to reach the necessary capacity, and an approximately $10 million budget estimate, Fences to hold the “Tent City” were constructed. With little to no timing to compete the task, the Commander, Colonel William J Moran, [7, p.1] completed his required task to create a facility capable of holding 15,000 refugees. A number shortly thereafter raised to 25,000, though the facility was never fully occupied.

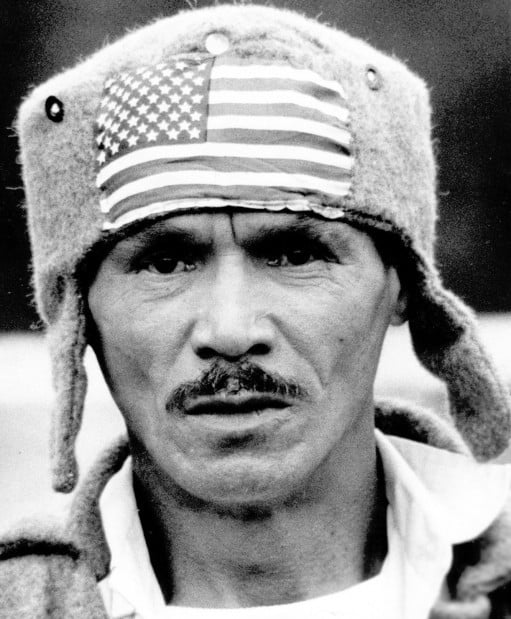

On May 29th 1980, the first wave of refugees arrived, with 172 individuals. Hopes were high, the refugees had yet to experience the processing camps. “I hope the American government can establish some sort of relations with Cuba to help my family get to America,” a Fermio Roque-Soa said on arrival to the Stevens Point Daily Journal, [2, p.1]. Preparation had been underway for nearly a month, hospitals, quarantine areas, detention centers, and dining facilities had all been established, “We’re not fancy, but we get the job done,” Capt. James Essman reportedly said to The Daily Tribune, regarding an inflatable hospital, which had been propped up, and trucked from fort Campbell Kentucky, [1, p.1].

By June 10th, this number was 13,069. Every refugee was seeking sponsorship in the US, trying to establish a permanent place away from their homeland that had been weakened, in part, by US military and political intervention. “Federal officials said… [as of May 29th] only recently has the flow of refugees to Florida begun to slacken, giving the center a chance to catch up with processing,” [3, p.1]. The processing center was overcrowded, and people needed to find a way out. The public was urged to take on the refugees, find places for them to live, and work. Representative Joseph Czerwinski said to the Stevens Pont Journal that morning, there is a “need for persons and groups to sponsor refugees who need homes and jobs, that should help hasten the release of immigrants from the camp,” [4, p.1]. The overcrowding was bad, and anti-US sentiments were growing.

A camp spokesman issued a statement claiming that “Cubans accused of anti-US activity are being detained in separate quarters for their own protection,” [4, p.1]. This demonstrates the sentiments in the camp were moving towards a prison culture, between the barbed wire, confined living conditions, and now the clashing of clans within the centers- tensions were high. The immigrants needed to be either hosted by American citizens or moved to a more permanent facility, where they could be cared for and monitored to ensure the hostilities would deconflict.

By the end of July, the overcrowding in the refugee population center had led to the first homicide involving a Cuban refugee. According to the Stevens Point Journal, “Louis Alvarez Benite, 35, died after receiving a stab wound to the chest,” after being attacked by Juan Eugenio Armanaz-Marineza, [5, p.1]. This is evidence of the continues struggle by camp staff to maintain law and order in the camps. Some would say that this was inevitable, due to the close living conditions, and the rivalry’s that developed between the different people groups who had just recently been separated form their homelands, but it does not excuse the murder of immigrants in the camps. The only way to deescalate the situation was to distribute the immigrants among the population, and detain those that broke the law. However, as most refugees were resettled into America, many were not able to gain sponsorship. This led to the continuance of the heightened situation in the camps, whose occupants were eagerly searching to escape, and seek freedom in the general American population.

On September 7th, Cuban refugees protested their confinement against their will, and tore down the fence. [7, p.157]. This riot involved numerous Army units, which had to suppress the crowd using non-lethal suppression techniques such as deploying CS gas, and cordoning the entire refugee center. After careful examination, it was apparent that approximately 300 Refugees had knocked down approximately 7000 feet of the 8-foot Fence that surrounded the single male compound. Governor Lee S Dreyfus said to the Stevens Point Journal that he “demanded that President Carter tighten security to prevent numerous escapes of refugees,” further exclaiming, “the rebellious refugees must be thinking ‘Is this America? We came here and we are put in what looks like prison!’” [6, p.1]. As the riots continued, and the unrest became more severe, 400 soldiers were transported from Fort Campbell Kentucky to further reinforce the already 500 MPs stationed at Fort McCoy, and the 475 MPs temporarily on duty from Fort Carson Colorado. They had been placed into a formation surrounding the eight-foot-high chain linked fence, which not 24 hours before had been toppled by one quarter of the population of the containment area. These 1500 men were spaced eight to ten feet apart, surrounding the entire 7000-foot perimeter. [7, p. 157]. Security as of the highest concern.

The riots were started, largely over a rumor, which the military found out about the following day, that the US Catholic Conference had been selling refugees to sponsors. While this rumor was false, it is believed to have been spread due to the U.S. Catholic Conferences broadcasting background information to the rocky mountain region, in hopes of stirring interest in resettling the immigrants. In the end, the disturbance left 9 injured, including 5 MPs, one of which had to be taken to the hospital for massive head injuries sustained on September 7th, and the following riots on September 8th. Numerous other incidents occurred on the Fort McCoy installation that led to the creation of a barrier that had to be manned at all hours by full time, armed and ready to engage, Army personnel. This created a large amount of negative attention, which was detrimental to the local community. From runaway refugees, who were being held due to their undesirable nature, creating a menace in the community, to threatening the Military Police who were going to enforce the upcoming relocation to Fort Chaffee Arkansas.

In the first week of October, approximately 500 refugees were flown out of McCoy to Fort Chaffee Arkansas, [8, p.1]. This movement was the beginning phase of closing the camp for winter. Since the buildings across the installation were still made of uninsulated wood, the installation was only run during the warmer months. The initial time frame was to have the refugees inside the camps by the end of May, increase the population of the camps to a height of approximately 15000, and relocate them to sponsors by the beginning of September. Since this goal of finding sponsorship for all the refugees was not possible in this timeline, the camps were forced to run for an extended period, while they relocated all the refugees who could not find sponsorship to a warmer region, until they finished their process of establishing a life in the United States.

By November 3rd, all refugees had either been sponsored, or relocated to Fort Chaffee Arkansas. After the bulk of the remaining refugees had been moved to Fort Chaffee, many juveniles from the juvenile wing remained. 84 of them were relocated to a youth camp, where 25 walked away. According to Eric Stanchfield, “They weren’t trying to escape, they had been locked up for three to four months and just went for a walk.” [6, p.1] By nightfall that day, most had been rounded up, but a few were still unaccounted for. By the following day, they had all been returned to the youth camp. This demonstrates the extreme extent of the camps natures. Living in such conditions for over 3 months, which for a child feels like an eternity, has a drastic effect on the psyche. This further makes clear the extent to which the American sentiment to the Cuban refugees had developed. By the end of the resettlement process, the American Population had become convinced that Fidel Castro had sent Cuba’s worst. They had been convinced Castro had sent his rapists, homosexuals, thieves, and incompetents to rid the Cuban lands of their unwanted lives. The reality was, most of the Cubans who came to America were hard working, and just didn’t expect to live in prison upon escaping the oppressive regime back in their homelands. As time went on, the Cubans earned their place in American society, and the grander American culture.

The total reported operating cost of the operation was approximately $29.5 Million, which has a 2017-dollar adjusted value of approximately $95 million, [8, p.1] That value, averaged over the number of refugees comes to an adjusted cost of over $6000 per refugee. It should be noted that a large portion of that cost was the cost of paying for transport to and from Fort McCoy and the cost of civilian and military staff on the installation to construct, operate, and dismantle the facilities.

Throughout the time Fort McCoy was inhabited by the refugees, an incredible amount of money was spent, riots formed, and lives were lost; but an incredible humanitarian effort was achieved. Over 125000 refugees were accepted into the United States, after landing on the beaches of Florida. What at first caused shocked the Miami beaches they landed on. Staging sites had been established to award the refugees their appropriate status as political asylum seekers. Without the use of federal military bases, the successful adoption of these refugees into America would have been impossible. Through a partnership between civilians and military, the Cuban resettlement was possible, albeit at a large expense to the local communities, and military readiness at crucial training facilities such as Fort McCoy.

Primary Sources

- 1. Associated Press. “McCoy Medical Team Ready for Refugees.” The Post Crescent, 29 May 1980.

- 2. Associated Press. “First Cubans Arrive at Fort McCoy.” Stevens Point Journal, 29 May 1980.

- 3. Associated Press. “Legislators Tour Refugee Camp.” Wausau Daily Herald, 10 June 1980.

- 4. Associated Press. “Lawmakers Question Plans for Refugee Resettlement.” Stevens Point Journal, 10 June 1980.

- 5. Associated Press. “McCoy Stabbing Victim Identified.” Stevens Point Journal, 02 August 1980.

- 6. Associated Press. “Refugee Disorder Blamed on Rumor.” Stevens Point Journal, 09 September 1980.

Secondary Sources

- 7. Department of the Army, (2005). 25 years ago: Fort McCoy supports large Cuban Refugee Operations Mission. Fort McCoy, WI.’

- 8. Department of the Army, (1982). Task Force Resettlement Operation After Action Report. Fort Sill.

- 9. Aguirre, B. (1994). “Cuban Mass Migration and the Social Construction of Deviants.” Bulletin of Latin American Research,13(2), 155-183

Further Reading

- Jones, Meg. (2016). “National Guard Veteran Remembers Cuban Refugees at Fort McCoy.” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- Rindfleisch, Terry (2005). “When Cubans and Chaos Came to Fort McCoy that was in 1980.“La Crosse Tribune.

- Molczan, Ted. (2015). Ft._McCoy_1.txt

- US Army Forces Command, (1984). The Role of Forscom in the Reception and Care of Refugees from Cuba in the Continental United States.

- Fournier, Linda (2008). Fort McCoy.