Many people often forget the losing commanding officer in a war or battle. Sometimes it is at the fault of the commanding officer for the outcome of the battle, and sometimes it is out of their control. The latter was the case for Robert Heriot Barclay, an officer in the royal British navy. His successful start to his young career would take a turn in a major battle of the War of 1812 with the United States. He would go on to lose a battle that significantly helped the Americans, maybe even changing the outcome of the War. Even though he was not victorious, his role in the war and in the Royal Navy is not overlooked.

Robert Heriot Barclay was born in Kettlehill, Scotland in September of 1786. He was the son of Reverend Peter Barclay, husband to Agnes Cosser, and a father to many children. With a ‘ready to learn’ mentality, Robert was able to join the Royal Navy at the age of only eleven. His young appointment as a midshipmen may have come as a result of his Uncle’s high status as an Admiral in the Royal Navy. Nevertheless, this early start may have lead to Barclay’s early success as an officer. As he gained more confidence and showed more leadership, he quickly rose in the rankings. But in 1809, Barclay lost his left arm commanding a battle between the British and the French. As a 12 year veteran, but only 23 years old, Barclay did not let this major setback stop his career in the navy. After he was fully healed, he rejoined his colleagues on the sea until his luck brought him to America in 1813. He had a relatively short stay in the U.S, but left with two more injured appendages; an arm and a leg. This was due to a terrible defeat in the Battle of Lake Erie; a commanding role only given to him because another officer turned down the job. After suffering more life altering injuries, only a truly determined man like Barclay could remain in the Royal Navy for the next 11 years before his retirement. Although only gaining 1 more promotion after a terrible defeat, one can say that his career was still a success. One thing is certain; his loyalty to the Royal Navy cannot be questioned.

At the beginning of the War of 1812, given that the British Royal Navy had the advantage over the small but growing U.S navy, Lake Erie was quickly taken control by the British. The only American war vessel on the lake was quickly taken by the British.

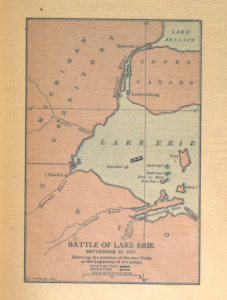

A year later the American forces have made base at Presque Isle, Pennsylvania. With a relatively small number of men to defend a whole lake, a well defended base, and a growing American Navy, the officer nominated to be in charge of the Lake Erie campaign turned down the job due to clear conditions for failure. Such an act almost lost this man his job in the Royal Navy. Barclay was the next man up, and with the tides of Lake Erie making a turn, he was doomed from the start. In July of 1813, with his main ship not properly equipped in the cannon department, Barclay decides to make a blockade of the American base at Presque Isle. After a week and half, the blockade strategy had to be abandoned due to supply shortages. With the American fleet complete, the U.S commanding officer Oliver Hazard Perry did not waste any time. His nine ships arrived in Put-In-Bay, Ohio to join with reinforcements. Not too long after, Perry’s fleet went searching for the American’s to win a decisive battle and maybe end the war of Lake Erie.

In the morning of September 10, the American’s spotted the British fleet approaching and sailed out to confront the enemy in the open seas. As the action started, Oliver Perry famously raised his flag that read ‘don’t give up the ship’. In one of the most hypocritical historical accounts, Perry hopped in a rowboat and rowed to an adjacent ship due to his being bombarded with cannon fire .Safely on the ‘Niagara’, Perry raised his flag once again after leaving the Lawrence. While Robert Barclay was attempting to reform a line, Perry took decisive action and charged toward the British, taking them by surprise. Theodore Roosevelt describes the accounts “At quarter to three the schooners had closed, and Perry bore up to break Barclay’s line, the powerful brig to which he had shifted his broad pennant being practically unharmed, as indeed were his rearmost gun-vessels.” Other American ships followed Perry’s and did so much damage that Barclay was forced to surrender within minutes.

Barclay was not the one to blame for this defeat, although his role as a commanding officer would be questioned after such a critical loss. After losing part of his leg and injuring his remaining arm, Barclay explains the situation in a letter written by him to Sir James Yeo, the commander of the Royal Navy on the Great Lakes; “The last letter I had the honor of writing to you… I informed you that unless certain intimation was received of more seamen being on their way to Amherstburg, I should be obliged to sail with the squadron deplorably manned as it was, to fight the enemy (who blockaded the port) to enable us to get supplies of provisions and stores of every description, so perfectly destitute of provisions was the post, that there was not a day’s flour in store, and the crews of the squadron under my command were on half allowance of many things…” [Paullin, 67]. The Americans had made a blockade of Amherstburg, cutting off the British supply lines. With supply’s running low, Barclay knew he might have to attack the rising American fleet with his ‘deplorably manned’ squadron. When no word of reinforcements to Amherstberg was heard, Barclay had to make the tough decision to face the American’s head on.

In the same letter to Commander Yeo, Barclay briefly explains how his pre-battle strategy was foiled by mother nature. “…soon after daylight they were seen in motion in Putin Bay, the wind then at south west and light, giving us the weather gage; — I bore up for then in hopes of bringing them to action among the islands but that intention was soon frustrated by the wind suddenly shifting to the south east, which brought the enemy directly to windward.” [Paullin, 68]. With the American ships outnumbering the British 9 to 6, Barclay thought a battle within the islands could gain an advantage for his smaller fleet. Waiting until the winds were just right for such a battle, Barclay advances. Then the winds shift in favor of the Americans, and also draws the battle onto more open seas. Barclay had nothing left to do but stand his ground and hope his men fight harder than the opponent. Barclay describes his frustrations; “The weather-gage gave the enemy prodigious advantage, as it enabled them not only to choose their position, but their distance also, which they did in such manner as to prevent the carronades of the Queen Charlotte and Lady Prevost from having much effect…” [Paullin, 71].

Credit must also be given to Oliver Hazard Perry. Although he gave up his ship, he was still able to make a quick tactical decision that was the key to bringing his side to victory. He also was able to stall the British attacks to when his fleet was large enough to face the enemy directly

Just 6 days after the Battle, a trial was held for Barclay for the loss of his flotilla on Lake Erie. Luckily for him, the court recognized that he was given inadequate men and supplies. They stated his actions to confront the American’s were justified. In the official statement of the trial, “…the capture of His Majesty’s late squadron was caused by the very defective means Captain Barclay possessed to equip the vessels on Lake Erie…” [Paullin, 138]. After the trial and recovering from his injuries, Barclay somehow continued to serve in the Navy for 11 more years until his retirement in 1824. He was promoted to captain and th

The British Royal Navy did not live up to it’s reputation on September 10, 1813. The mistakes made in the campaign to control lake Erie came from positions of high stature, who obviously underestimated the American’s. The American’s had a total of only 20 naval ships at the start of the war. With a grand total of zero on Lake Erie, the British thought the war would be over before any sort of force could be constructed. Even though the British were not well prepared as well, their navy was supposed to be the best in the world. As the war continued, priorities were made, and resources had to be distributed to areas of higher density of battles. Lake Erie was not such a place. Underestimating the American’s and the importance of control of Lake Erie, the British made a large mistake by conceding Lake Erie. The American control of the Lake helped wrap up the fighting in the Great Lakes region, giving them ships, cities, and morale to take to other areas of the war.

Primary sources

- Bancroft, George, and Oliver Dyer. History of the Battle of Lake Erie: And Miscellaneous Papers. New York: Robert Bonner’s sons, 1891. Print.

- Marshall, John. Royal Naval Biography : Or, Memoirs of the Services of All the Flag- officers, Superannuated Rear-admirals, Retired-captains, Post-captains, and Commanders, Whose Names Appeared on the Admiralty List of Sea Officers at the Commencement of the Present Year, Or who Have Since Been Promoted, Illustrated by a Series of Historical and Explanatory Notes … with Copious Addenda: Captains. Commanders. London, 1831. Print.

- Parsons, Usher. Brief Sketches of the Officers who Were in the Battle of Lake Erie. Albany N.Y: New England Historical and Genealogical register. 1862. Print

- Paullin, Oscar. The Battle of Lake Erie: A Collection of Documents, Chiefly by Commodore Perry: Including the Court-martial of Commander Barclay & the Court of Enquiry on Captain Elliott. Cleveland: The Rowfant Club, 1918. Print.

Secondary sources

- Altoff, G. T. (1988). Oliver Hazard Perry and the Battle of Lake Erie. Michigan Historical Review, Vol. 14 ( No. 2). pg. 377-388.

- Hill, W. (1914). THE NAVAL HISTORY OF LAKE ONTARIO AND LAKE ERIE IN THE WAR OF 1812. Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association, Vol. 13, pg. 377-388.

- Robert Heriot Barclay. National Parks Service.

- W. A. B. Douglas, “BARCLAY, ROBERT HERIOT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed October 11, 2015.

- Armstrong, John. Notices of the War of 1812: Volume 1, 1840. Print