For clarification, I will use name Dakota when referring to the tribe instead of the commonly used name Sioux, as it roughly translates to “rattlesnake” in the Lakota language.

The Siege of Fort Ridgely was, along with the battle for New Ulm MN, the turning point of the Dakota Uprising of 1862. After this, the Dakota suffered defeat after defeat until they were either killed or captured. The battle of Fort Ridgely would be the first successful use of artillery against native forces, emphasizing their importance in later Indian wars. It also showed the desperate situation of forcing civilians, including women and children to help fight off the Dakota. This was emphasized by the Dakota use of no quarter. While friendly Dakota did help civilians escape the violence, the bloodshed burned the image of the savage native farther into the minds of the frontiersman, deeply harming native relations to this day.

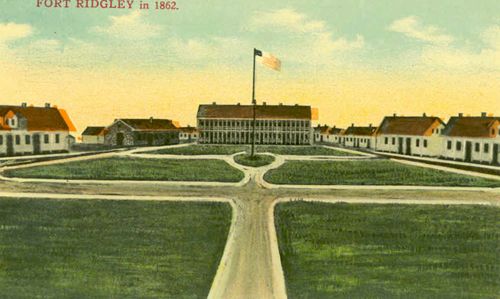

Fort Ridgley, located in the border of the Lower Agency, was originally established in 1853 to facilitate the promised tributes to the Dakota for moving onto their reservation. This fort was little more than a bunch of buildings garrisoned by a dozen or so troops with 4 cannons and one howitzer. During the Dakota Uprising, it was used by the fleeing frontiersmen as a safe point before fleeing to the Twin Cities defended by Fort Snelling. It was reinforced by the 3rd Minnesota volunteers commanded by Lt. Sheehan in the goal of fortifying Fort Ridgely in the hope that along with the city of New Ulm, MN, creating a line of strong points and stockades to hold, or at least by time to defend St. Paul, the capital of Minnesota, and to call up help from the National government.[3]

The Dakota Uprising in 1862 in the Lower Agency in the southeast of Minnesota and parts of western North and South Dakota, was caused by a combination of overhunting and bad crops by the Dakota, and the inability of the Lower Minnesota Agency to pay its promised annual royalties of food, blankets, and money to the Dakota due to the supplies being diverted to the American Civil War. When the Dakota asked for supplies from a local merchant in exchange for debt, they where told to “Eat some grass”. This caused some of the Dakotas who felt their inability to prove themselves as men by combat, and the ravages of starvation, to be forced to raid frontier houses and farms for food and supplies in order to survive. Little Crow, one of the leading leaders of the Dakotas, reluctantly agreed to raid the frontier for supplies. The younger men of the tribe used this opportunity to seek revenge for whites for forcing the Dakota onto reservations. Such led to the massacre of men, women, and children trying to escape west away from the frontier. This is best summed up by the recollections of Helen Carrothers with her neighbors and family trying to escape to the safety of Fort Ridgely when they were stopped by a band of Dakota warriors and she asked what they wanted in their native language. “We are going to kill you all” ,was the reply. [3]

The Dakota Uprising Begins

(legendsofamerica)

On August 18th, 1862, Captain Marsh took the advice of Peter Quinn, a Dakota translator who had a good understanding of the Dakota from 40 years of experience, saw the grave situation on the Lower Agency. Marsh took 50 men under his command and marched towards Faribault’s Hill in order to fight a delaying action to give the frontiers people time to escape east. Knowing it was most likely a suicide mission, he said,

[5]

“I am sure we are going into great danger; I do not expect to return alive. Goodbye; give my love to all”

Later that afternoon, Captain Marsh and his 50 men were ambushed at the ferry at (Redwood’s Ferry). After trying to communicate with several armed Dakotas, a dozen men were killed and even more wounded. The surviving men lead by the senior survivor by rank, Sergeant Bishop, hastily retreated to Fort Ridgely that night. [4]

He left Lieutenant T.F Gere with 25 men to hold the fort. Before departing the fort, he told the Lieutenant to send a messenger requesting Lt. Sheehan to return to the fort, which the previous day in which he was called fort Ripely. Lt. Gere then sent Corporal James C. Mclain to fetch Lt. Culver, commander of the Renville Rangers, who had been ordered to report to the town of St.Peter, to return to the fort.Later that afternoon, Captain Marsh and his 50 men were ambushed at the ferry at (Redwood’s Ferry). After trying to communicate with several armed Dakotas, a dozen men were killed and even more wounded. The surviving men lead by the senior survivor by rank, Sergeant Bishop, hastily retreated to Fort Ridgely that night. [4]

Around noon, Lieutenant Gere sent Lieutenant Thomas P. Sturgis to ride to the governor in St.Paul to ask for reinforcements while also giving the order to Lt. Sheehan to return. Upon leaving the fort, Sturgis saw C.G. Wykoff, the clerk of the Indian Superintendent, arrive around noon in a wagon with the $750,000 in gold that was the Dakota’s tribute. This was desperately needed two days prior in order to pay for food, which was one of the root causes of the uprising.

Sturgis met Lt. Sheehan sometime around 3am in the morning on August 19th. Sheehan, upon reading this message, ordered his men back to the fort, covering 23 miles. Upon reaching the fort, Lt. Sheehan found 22 men remaining who were still able to fight, along with the Renville Rangers, a volunteer brigade, commanded by Lieutenant Culver, mostly made up of local “half-breeds”, men that where half Dakota and half frontiersman, who understood both societies and who spoke both languages. Sheehan did not completely trust them as he did not know with who they allied. Lt. Sheehan would later be pleasantly surprised to find that all but one of these “half-breeds” would remain absolutely loyal.[2] The fort was also crowded with refugees (about 500), seeking shelter from the surrounding area, with a constant flow in. Most were women and children, as men were often killed trying to buy time for their families to escape before Dakota had surrounded them.

John Jones deserves a particular mention. Jones had seen action in the Mexican-American war 1846-47 with an artillery battery, and was the ordnance sergeant of the fort. Due to his prior experience with the use of batteries in combat, he was knowledgeable enough to relate and train the refugees on how to properly load, maintain, and operate a battery under a commanding officer. This would allow for the fort to use all of its firepower to its full potential, with refugees fighting alongside the soldiers defending the fort in combat and non-combat activities. [4],[5]

Between August 18th and the morning of August 20th, Sheehan, the commanding officer by rank, ordered the construction of barricades mostly to the north of the fort. He also ordered the training of civilians and posted pickets by the ravines located all around the fort. The bulk of them to the northern face of the fort. Sheehan would later describe his position .

[1]

“On our arrival at Fort Ridgely I found that Captain Marsh and Twenty-three of his men were killed and several wounded, being the ranking officer I took command of the Fort. There was in the Fort Three hundred (300) refugees, men, women and children, I organized the best I could with one hundred (100) soldiers and eighty (80) citizens, and prepared for battle.”

Sheehan successfully predicted that the Dakotas would use the ravines to move around their flanks undetected. They would then try to have the defenders overly fortifying one side of the fort, only to have them attack on the opposite side of the fort in strength in order to breach the defences, forcing hand-to-hand fighting. The Dakota could then use their overwhelming numbers to its full advantage.[5]

In order to avoid this, Sheehan gave sub-command to 5 other officers. Lieutenant Gere, John C. Wipple, Sergeant John Jones and Sergeant McGrew would each command a battery at each corner of the fort. Sergeant Culver, the commander of the Renville Rangers, would join McGrew at the southwest corner along with John Jones commanding the battery at that corner. It was the closest corner to a reverend that Sheehan assumed would be heavily attacked. He ordered his officers not to redeploy their men to other areas of the fort unless a breach in another part of the fort was certain.

The Dakotas were spotted late in the day of the 19th reckoning for the war council on that night. This meant an attack was very like the next day.

Jones, knowing of the importance of the batteries, inspected the batteries before the battle. He had found that the batteries had been spiked by putting rags and stuffing them into the cannons. It was found that one of the Renville rangers had stuffed the cannons and was planning to desert that night. Jones, using his knowledge of the batteries from the war with Mexico, was able to make all the cannons operational by 1 pm the following day, and make the howitzer operational on the 21st. [4]

Combat on the August 20, 1862

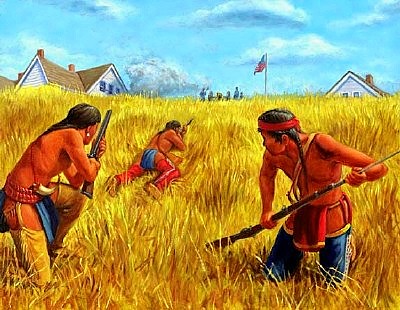

(Counter-Currents)

At 1 pm on August 20th, Little Crow rode out on horseback alone to the west side of the fort within sight of the fort, but out of musket range (about 1 mile). Little Crow hoped by doing this, the fort’s defenders would try to attack him, where his warriors hiding in the ravines behind him would then attack the defenders on open ground, using their numbers to annihilate the damnedest so to avoid an unnecessary frontal attack. Sheehan and his men did not take the bait, so Little Crow had his warriors attack the northern part of the fort, hoping to break the line somewhere around the northeast corner of the fort. The warriors made their way under heavy canister shot and volleys from musket fire. They were able to make it to the old lodging quarters buildings but were unable to continue, forced to use those buildings for cover.[5][6][8]

Seeing this,Little Crow ordered diversionary attacks from the south, southwest, and west, hoping to divert troops from the northern line of the fort so his warriors could then break through. All the diversionary attacks were repulsed, however. The attacks from the south and west were able to initially captured the large barn and settler’s store before being repelled by musket volleys. This lead to all of the attacks seeing the warriors trying to fire accurate rifle fire from concealed positions in buildings and the tall grass, but not advance any farther. At the same time, since the cannon ammo was stored in magazines located far west of the fort in order to prevent a magazine explosion from destroying the whole fort, now meant that ammo had to be carried 1 mile from the magazine to the gun out in the open with their flanks exposed. This heroic transition of cannon ammo from the magazines to the barracks, made of stone, took one or more hours, exhausting the civilians carrying the ammo. Combat continued until around 9 pm and saw the warriors fall back to their encampments.

(Exploring the off-beaten path)

The 21st saw heavy rains and no combat. The defenders used this time to build barricades on the southwest corner and convert the wooden roofs of the buildings with earthworks. Dakota warriors passed the fort to assaulted the town of New Ulm. Four hundred and fifty new warriors joined Little Crow’s force instead and sometimes briefly probe the defensive lines.

Lt. Sheehan was uncertain they could not survive another sustained attack in a letter he wrote to Governor Ramsey, the current governor of Minnesota.

“We can hold this place for a little longer unless reinforced. We are being attacked almost every hour, and unless assistance is rendered we cannot hold out much longer. Our little land is becoming exhausted and decimated We hoped to be reinforced today, but as yet can hear none coming.”

[1]

Combat on August 22, 1862

(Exploringtheoffbeatenpath)

At 9 am on the morning of the 22, Little Crow had his warriors attacked on all sides of the fort, with the main attack on the southwest corner. Little Crow hoped by attacking all sides simultaneously, he could stretch the defenders thin enough to breakthrough. The bulk of his forces attacked the southwest corner because the defenders could only bring to bear one cannon there. The warriors took the same buildings as they previously had, but then stalled. Around 4 pm, Little Crow ordered all of his warriors to attack the north side of the fort to redeploy to the southwest corner, moving west out of musket and cannon range, using the veins to move undetected. Seeing a considerable size of Little Crow’s force moving into the east ravine, Jones asked for permission for McGrew and him to fire shrapnel metal shot and for the Howitzer (under Bishop) to fire on the east ravine. Sheehan agreed and the effect was that the warriors were bunched up in the ravines when shrapnel metal shot prevented them from leaving the ravine, while the Howitzer was able to fire in-direct rounds into the ravine. This not only badly delayed the redeployment of troops and casualties, but it was also the place Little Crow had picked as an encampment site so he could see the battle up close and undetected.[4]

The delay in the day meant that Little Crow only had time for one more attack. It also gives the infantry time to tear into the bags of powder and caps meant for the canister shot to use in their muskets and take iron bars meant for making tools in the blacksmith, to create cylindrical ammunition due to the supply of normal ball and powder running out. This may seem like a smart move, but this is a very desperate one. Although cannon caps and powder can be used in small arms, the larger caps from the artillery do not fit in the muskets, and the bigger grain of cannon powder over small arms powder can lead to greater stresses on the barrel of the musket, causing the gun to rupture when fired, greatly injuring or killing its user. Since muskets were used, cut down iron cylinders could be used in the muskets as a substitute as a lead ball. It greatly reduced the already minimal accuracy of the musket, as well as permanently damage the musket barrel over time. The Iron rods that were too large to be placed inside of a musket were handed to the refugees to use as a weapon if hand to hand fighting broke out.[5]

Later in the afternoon, Little Crow had finally redeployed enough of his men for one final massed charged he hoped would finally break the defender’s lines. This was recognized by Sheehan and the rest of the officers. They had the rest of the defensive lines skeletonized and moved to the southwest corner, the Howitzer loaded and aimed, and Jones had the battery at the corner double charged. This means that instead of loading one canister or shell into the gun, he loaded two. While this may work due to a canister shot acting very similar to a shotgun blast, it would most likely ruptured the gun sending debris all over, killing or injuring the defender. If it worked, almost a wall of lead balls would be fired at the attackers. Knowing that they would need all the firepower they could get, as well as most likely not have enough time to load the battery before getting overrun, Jones chose to risk it. Right before the frontal attack occured, the Renville Rangers, able to understand the Dakota language, notified Jones of the impending attack while taunting the Dakotas back.

The result was the warriors, taking massive casluties, advanced to within a few feet of the defenders, with a dozen or so engaging in hand to hand combat. They even tried shooting flaming arrows to try and burn the wooden roof of the headquarters builder, but were unable to due to the earth added the roof and the heavy rains from the previous day. Eventually, the advance was halted, and Little Crow, fearing reinforcements from St.Paul and being unable to take the fort, used the cover of darkness to withdraw.

Lt. Sheehan recallled this moment,

“ With cheering and hurrahing of the Fort’s gallant defenders rejoicing among themselves over the victory this afternoon’s hard fought battle, against those blood thirsty devils who were eager and anxious for Therefore, it caused confusion in the camp with a lot of the horses and stolen livestock runnin our lives and scalps as hungry wolves would be for blood and with the Indians retreating from our front just as the red setting sun was going down in the West on the 22nd day of August,1862 at Fort Ridgely, it descended those red flashing and beautiful rays on the fort and its surrounding taking in complete Little Crow’s Camp, his warriors, squaws, dogs, ponies and papooses who were all in Camp one mile wst of the Fort on the banks of the Minnesota River, and those lighting rays before dusk forming a marriage whose sunset before us which could be plainly seen for about ten seconds, was the most magnificent sight and grandest and most sublime panorama that God ever allowed mortal men to look at or witness on this earth…”

[1]

While Little Crow had withdrawn his warriors, the defenders thought he was still lurking nearby, waiting for the defenders to leave the cover of the fort to fetch water from the nearby river, leading to the defenders holding out and building more barricades. They were out of all ammo minus a few rounds of canister shot, and a few rods that could fit in the muskets.

The defenders remained alert and deprived of sleep until the relief by Colonel Samuel Mcphil and William R. Marshall on the 27th of August with 175 armed mounted civilians and Sturgis, the carrier dispatched on the 18th to go to St. Paul for reinforcements.

The fact that Little Crow never did attempt to use a night attack where the defenders would not be able to open distances of the fields for a firepower advantage is unknown as I could find no sources recounting Little Crow’s thinking. He died shortly after the Battle of Fort Ridgely.

Primary Sources

- Sheehan, Timothy J., et al. Timothy J. Sheehan Papers, 1857-1913. 1858.

- Wall, Oscar Garrett. Recollections of the Sioux Massacre an Authentic History of the Yellow Medicine Incident, of the Fate of Marsh and His Men, of the Siege and Battles of Fort Ridgely, and of Other Important Battles and Experiences. Printed at “The Home Printery”, 1909.

- Howard, John R. “The Sioux War Stockades.” Minnesota History, Sept. 1931, pp. 301–303.4.Connolly, A. P. A Thrilling Narrative of the Minnesota Massacre and the Sioux War of 1862-63: Graphic Accounts of the Siege of Fort Ridgely, Battles of Birch Coulee, Wood Lake, Big Mound, Stony Lake, Dead Buffalo Lake and the Missouri River. A.P. Connolly, 1896.

- Connolly, A. P. A Thrilling Narrative of the Minnesota Massacre and the Sioux War of 1862-63: Graphic Accounts of the Siege of Fort Ridgely, Battles of Birch Coulee, Wood Lake, Big Mound, Stony Lake, Dead Buffalo Lake and the Missouri River. A.P. Connolly, 1896.

Secondary Sources

- Walsh, Kenneth Lee. A Biography of a Frontier Outpost, Fort Ridgely / by Kenneth Lee Walsh. Thesis (M.A.)–University of Minnesota, Duluth, 1957., 1957.

- Verril, Hyatt A. “The American Indian.” The Quarterly Journal of the University of North Dakota, vol. 18, 1927, p. 82.

- Russo, Priscilla Ann. “The Time to Speak Is over: The Onset of the Sioux Uprising.” Minnesota History, vol. 45, no. 3, 1976, pp. 97–106.

- Lass, William E. “Histories of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.” Minnesota History, vol. 62, no. 3, 2012, pp. 44–57.