The Canadian Car and Foundry Company was a steel works and vehicle manufacturing company, originally from Montreal but with a site in what would become part of Thunder Bay, Ontario. At that time it was called Fort William, and it was at that site that the Inkerman and Cerisoles were constructed in the year 1918, along with their ten sister ships that were successfully delivered to the possession of the French government. The French Navy had contracted Canadian Car and Foundry to build these twelve minesweepers in the final year of World War I, despite the fact that Canadian Car and Foundry had never had a history of building ships, especially vessels of war. This contract is one of the reasons why Canadian Car and Foundry saw substantially higher earnings in fiscal year 1918 than in 1915 or 1920, for example. The Inkerman and Cerisoles were the final two of these vessels built, and by the time that they were completed the armistice between the Allies and the Central Powers had been declared at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of that year.

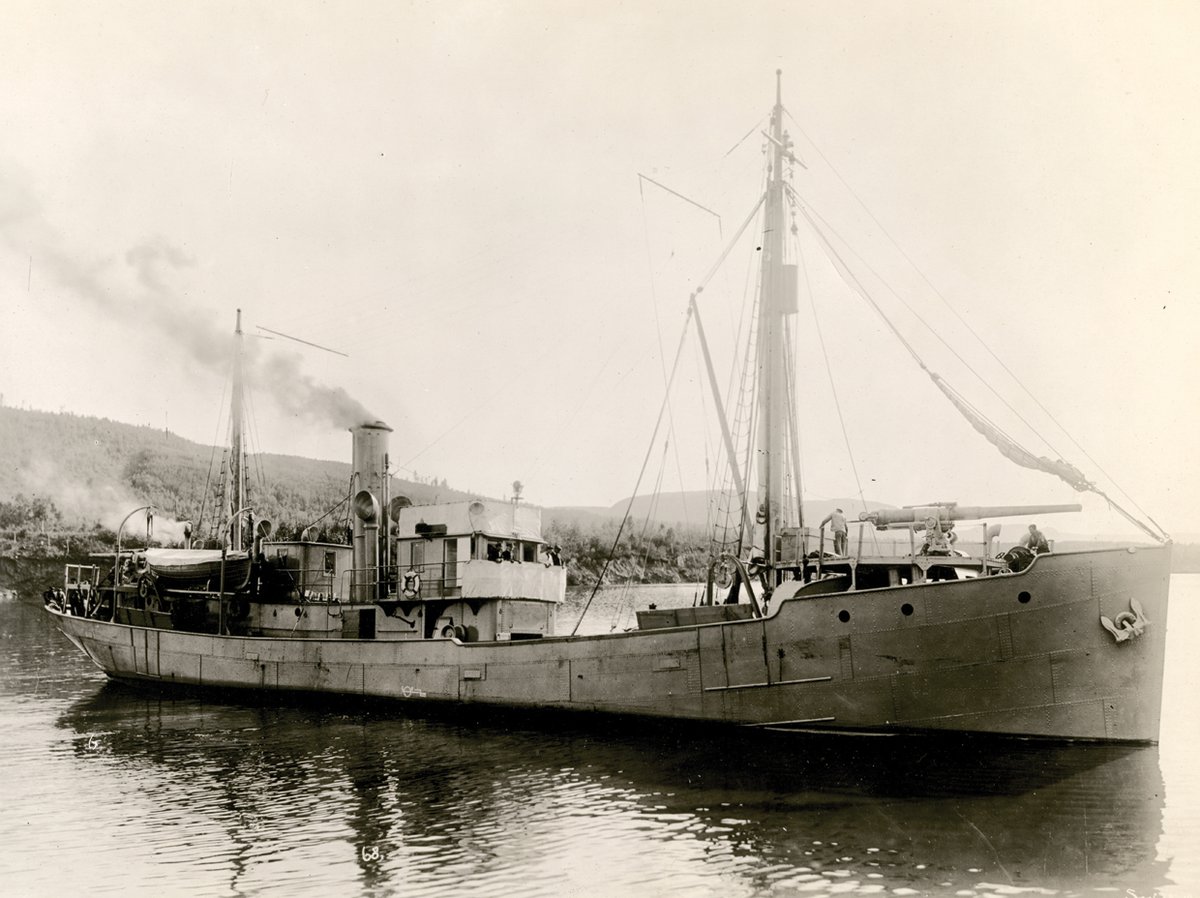

These ships were designed to be minesweepers in wartime, specifically to clear German mines out of the English Channel and thus provide for the safety of shipping between England, France, and other nations, but they were also designed to be easily converted to fishing trawlers following postwar service. All twelve ships built by the Canadian Car and Foundry Company at Fort William were built with this postwar function in mind, and for this reason they were designated as “trawler minesweepers” or “chalutiers” in the French language. They were built with wooden hulls over steel frames at 140 feet long, and each of them displaced 630 tons and had four independent watertight compartments to help prevent sinking. These twelve particular ships were of the Navarin class of trawler minesweepers, named for the first of the group built, which in turn was likely named for the Battle of Navarino in October 1827, a victory for French naval forces alongside their British and Russian allies. The first nine of the Navarin class sailed for France prior to the completion of the ships about which this story is told.

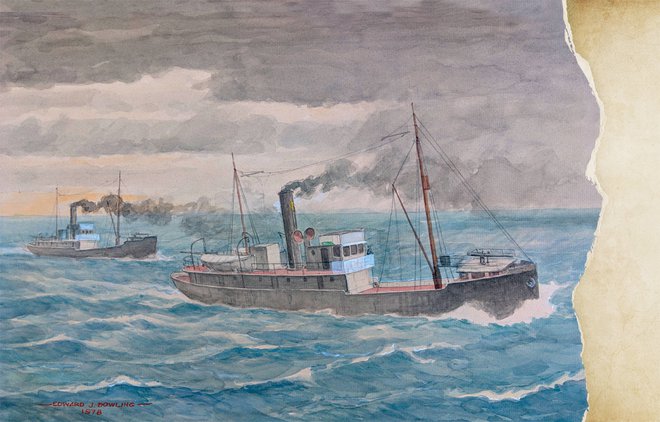

The final three ships built under this contract, the Inkerman, the Cerisoles, and the Sebastopol (all named for French victories in the Crimean War) left Thunder Bay on their way to Sault Ste. Marie and eventually France via the Saint Lawrence Seaway. The three of them travelled south from the city of their origin, and the lead ship, Sebastopol, made it past Isle Royale before the wind picked up and the waves began to grow. The commander of this small group of minesweepers, First Lieutenant Marcel Leclerc, turned the formation to the south with the plan of passing Copper Harbor, sailing around the tip of the Keweenaw, and sheltering in the protected waters of Bete Grise Bay. It was in the main body of the big lake, in between Passage Island, near Isle Royale’s northern end, and Copper Harbor, that the three ships lost sight of each other. The officer in charge saw his ship, the Sebastopol, make it to sheltered waters, but not without trouble. The blizzard that struck them was recorded to have winds of up to fifty miles per hour and waves up to thirty feet in height, and so it could be said that the French minesweeping vessels faced the gales of November that a particular Canadian singer and songwriter made famous decades later. One of the sailors on board First Lieutenant Leclerc’s ship Sebastopol was noted as describing the storm as life-threatening, saying that the sailors had to ready the life boats and prepare for leaving the ship, and that he had already given himself up to God. The Sebastopol’s engine compartment was flooded, and the fires of coal that were responsible for propelling the ship were very nearly put out. After at least one day of enduring the storm, First Lieutenant Leclerc and his ship finally made it to safe waters and eventually to the Soo Locks at the east end of Lake Superior.

During and immediately following the storms, First Lieutenant Leclerc failed to see or hear any sign of his two companion ships, the Inkerman and the Cerisoles. On account of the conditions and the state of the radio equipment (still relatively new in this application at the time of the First World War, and potentially damaged by the storm), the crew of the Sebastopol failed to make radio contact with either of the other two minesweepers’ crews, and First Lieutenant Leclerc assumed that they had weathered the storm and continued on his journey to the lock complex at Sault Ste. Marie and into Lake Huron beyond. The Sebastopol waited at the Soo Locks for a number of days before continuing on the assumption that its sister ships had beaten them there and carried on with the journey.

By the time that the Sebastopol had reached Lake Ontario, the Inkerman and Cerisoles had not yet reached the Sault Ste. Marie locks, and the Sebastopol reversed its course and returned to Lake Superior’s waters to help in the search for its sister ships. A widespread search was conducted, but neither of the craft were ever found. It is unknown how exactly they sank, but it has been theorized that the two large 100mm artillery pieces, one on the bow and one at the stern of each Navarin class minesweeper, made the ships unstable in heavy weather and may have been a contributing factor in the foundering of the Inkerman and Cerisoles From the French Navy there was a crew of thirty nine men on the Inkerman and thirty eight on the Cerisoles, each accompanied by a pilot of Canadian origin, Captains R. Wilson and W.J. Murphy. All of these seventy nine men died in the pair of shipwrecks, and no definitive evidence of any of their remains has ever been found. These two shipwrecks, taken together, represent the largest loss of human life to ever occur in Lake Superior, and the Inkerman and the Cerisoles are the two most recent ships of any military to be lost beneath the waves of the Great Lakes. Multiple efforts to find the lost ships have been undertaken over the decades since that fateful storm, including one recently conducted by Michigan Technological University, but in the case of these two French minesweepers Lake Superior has yet to give up her dead.

Sources

- French Ships Lost on Lake Superior (1918). Duluth News Tribune. 6 December 1918.

- The Equipment Companies (1923). Barron’s. 10 September 1923.

- Woodhouse, Christopher Montague (1965). The Battle of Navarino.

- Burkowski, Gordon (1995). Can-Car: a history 1912-1992. Thunder Bay.

- Bourrie, Mark (2009). “Treasure Hunters Seek Lake Superior’s ‘Holy Grail’.” Toronto Star.

- Vego, Milan (2015). On Littoral Warfare. Naval War College Review. 68.2: 20-68.

- Stonehouse, Frederick (2018). “Ils Sont Disparu! They Are Gone: The Baffling Fate of Inkerman and Cerisoles.” Lake Superior Magazine.