January 22, 1813 – the Battle of Frenchtown had just ended and American troops surrendered to the British. More than three hundred souls perished on the battlefield; those who remained were now prisoners, both healthy and wounded. The next day would bring about the bloodiest massacre of the war, much to the surprise of those taken prisoner, as they had been promised safe haven and travel to Fort Malden where they would wait out the rest of the war.

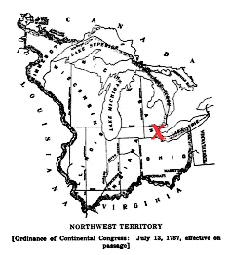

During the year of 1812, the United States went to war with England for a number of reasons, the most significant ones being that the British were attacking American merchant ships, kidnapping American sailors, and inciting Indian attacks supplied with weapons and resources that originated in Britain. The war officially broke out on July 18, 1812, when President James Madison declared war on Britain. In the first months of the war, the Americans lost a lot of ground, including Fort Detroit in the Michigan Territory. This was due to a lack of experience and organization in the American military. The loss of Detroit gave the British access to most of the Michigan Territory, which greatly affected the security of the Midwest. In January of 1813, a new commanding general, William Henry Harrison, was ordered to attempt to retake the village of Detroit.

In the days leading up to the bloody event that would become known as The River Raisin Massacre and inspire the battle cry, “Remember the Raisin!” American troops valiantly fought off the British, trying to recapture Fort Detroit if possible. Capturing this Fort would allow the Americans to have access to Upper Canada where the British troops were stockpiling their resources. The idea from General William Henry Harrison, the commander of the Army of the Northwest Territory, was that if the Americans held a winter campaign and were able to force the British out of modern-day Michigan, they would be able to put an end to the war. Under the orders of General Harrison, Brigadier General James Winchester set up encampment near the Maumee River Rapids. In his command were about two thousand troops from Kentucky.

After talking to some of the citizens in nearby towns, namely Frenchtown, General Winchester decided to send some troops to the north in order to relieve the town of the occupying British and Indians. This was against the orders that General Harrison had given him. Little resistance was met when they fell into a skirmish with enemy troops on 18 January, so all was seeming to go well. The successes of the troops caused Winchester to have too much confidence in their situation and settled down in Frenchtown without proper security set up. Despite the protests of the settlers of Frenchtown who adamantly told him that the British would be there at any moment, Winchester believed that it would several days before they would see any more British. This lack of judgment prompted him to stay over a mile away from the main body of his troops in Frenchtown and to have most of the gun powder with him. Come the next morning, this would be the biggest mistake.

The Battle of Frenchtown (River Raisin)

The British attacked in the wee hours of the morning on the 22nd of January, 1813. They numbered close to 600 regular British soldiers and more than 800 Indians, greatly outnumbering the American forces occupying Frenchtown. Due to the poor placement of guards the night before, the American troops were not certain that they would be able to hold the town. General Winchester, a mile away, was woken up by the sounds of the battle and arrived just in time to watch as the right flank was dissipating. In a final attempt to maintain their ground, Winchester tried to regroup on the other side of the River Raisin, but the British forces snuffed out their efforts.

Back in the town, the Kentucky volunteers were still holding their line. Their ammunition was low but they were keeping the enemy at bay. When a flag of truce came from the British lines, they thought they had been victorious, except when they saw that the bearer of the flag was General Winchester’s aide. They had not heard of the surrender of the American regulars. Those who were not killed in the battle were shot or scalped by the Indian forces, causing the few who could escape to flee as fast as they could. General Proctor (the British commander) had convinced Winchester to surrender as he threatened to burn the town and the wounded would be killed by the Indians. Despite their vows to fight no matter the consequences, the Kentuckians surrendered when told that they would be protected from massacres by the Indians and all of their property would remain theirs, minus their firearms and ammunition.

The River Raisin Massacre (Elias Darnell)

Not knowing of the events that had already occurred with the regulars, the Kentucky volunteers began to settle in for the night of the 22nd of January. They had been promised that sleighs would arrive in the morning in order to transport the wounded who could not walk to Fort Malden, where they would wait out the rest of the war or until a prisoner exchange took place. They would soon find that they were wrong.

One survivor, Elias Darnell, talks of how the wounded who were left behind had to ask the British for food and noticed that there were no guards on the wounded. When inquiring about the location of the guards to protect them from a potential massacre, the British soldier replied that the Indian interpreters would be making rounds to make sure that everything was going as it should. In his diary, he stated,

“I asked him if there was a guard left ? He said there was no necessity for any, for the Indians were going to their camp, and there were interpreters left who would walk from house to house and see that we should not be interrupted” (Darnell, 58).

One Indian did come in to talk to the wounded, telling stories of how the Americans who surrendered to him and his men tried to pay money in order not to be killed. He laughed as he spoke of how his men would take the money and then tomahawk them there on the spot. The confidence of the men at this point was waning, as they were sure they would all be dead by morning.

Much to their relief, morning did arrive. Hopes were lifted, as the men waited and began to prepare for the arrival of the sleighs that had been promised to take them all to Fort Malden. Instead of sleighs, however, the only thing that arrived were Indians who had painted their faces in bright colors and started to bust into the various buildings in the town. American prisoners were pouring out without their coats, boots, or blankets; the Indians were taking them from them for their own. This again was against what the British had promised upon the surrender of the Kentuckians. Even more brutal were those who were setting fire to the houses. Wounded soldiers, some who had not risen from bed for days due to their condition, were trying to flee from flames; however, as they would exit the burning building, Indians would cut them down with tomahawks. The event in recounted in Darnell’s diary as he wrote,

“I saw my fellow soldiers, naked and Avounded, crawling out of the houses to avoid being consumed in the flames. Some that had not been able to turn themselves on their beds for four days, through fear of being burned to death, arose and walked out and about through the yard. Some cried for help, but there were none to help them. “Ah!” exclaimed numbers, in the ano-uish of their spirit, “what shall we do?” A number, unable to get out, miserably perished in the unrelenting flames of the houses, kindled by the more unrelenting savages” (Darnell, 60-61).

Some soldiers out of desperation tried to pay off the Indians. The same that occurred to the regulars happened, as they would take the money and then kill the man who gave it to them. Finally, with time, those who were still alive were rounded up and began a grueling march to Fort Malden. If they were to fall behind, their captors would kill them on site, showing no mercy. Darnell had to watch his brother, Allen, get murdered in such a way. During the march, he was then chosen by one of the Indians as his own and would be at their mercy until he was freed. His new owner gave him a coat and food to help him on the journey.

Eventually, they reached a village where there were a large number of British soldiers. Darnell asked two British officers what was to become of him and another wounded soldier who was with him. They merely replied that they would be taken to Malden and their fate was in the hands of the Indians, causing Darnell to believe that it was the British who had ordered the attacks to occur in the village of Frenchtown earlier that day. Darnell was one of few who was able to escape after three days, as he fled his Indian captors in the middle of the night without shoes or a good coat. Once he arrived in Amherstberg, he was free. Many of his compatriots were adopted by the Indians and forced to become a part of their families; some even had to marry an Indian woman.

Eyewitness Account of Thomas Dudley

Another witness to the attacks, Reverend Thomas Dudley, experienced similar things to Elias Darnell. He was present for the terms of surrender under which the Americans would be taken safely to Fort Malden and all wounded would be cared for as the British would care for their own soldiers. The Indians were not to touch a soul. This again was not true.

At sunrise, he saw Indians arriving, instead of the British with the promised sleighs. They went into a house where many of the officers who had been wounded were staying. In the cellar, there were a great many barrels of some type of alcohol, which they drank most of, causing them to become loud and rowdy. They burst into the room where Dudley and three other officers, all wounded, were staying. Dressers were torn open and the Indians ripped apart the beds in which Major Graves and Captain Hart had been staying. Captain Hickman was still in bed due to his wounds and the Indians tomahawked him within six feet of Dudley.

Dudley went to the porch in order to escape the room and heard Captain Hart talking to one of the interpreters. He asked why the Indians were mutilating people. The response was simple, “’They intend to kill you’” (Dudley, 3). He begged that the interpreter tell them to stop, but the interpreter insisted, “‘If we undertook to interpret for you, they would as soon kill us as you'” (Dudley, 3). Their attempts at pleading for their lives were futile. Captain Hart paid the interpreter $600 in order to spare his own life. He was put on a horse and they began their way to Malden but just a short way down the path, they ran into another Indian who demanded the $600 that the other had received. In response to this, the interpreter shot Captain Hart off his horse in order to settle the dispute.

Indians took charge of many of the officers, and Dudley refused several who came by him. In an attempt to get aid for the wound in his shoulder, he showed a few Indians, but they just ignored him and motioned for him to follow. He feared that he was in for a worse death and began wishing that they would shoot him down there. Finally, a warrior passed him and saw his poor condition. He gave him a blanket and tied it around his shoulders in an attempt to keep him warm. A few hours into the march, the same warrior saw that he was without shoes and gave him a spare pair of moccasins.

Upon reaching Detroit, women in the streets tried to beg for the prisoners’ release, but they were ignored. All of the soldiers who had been taken prisoner surrendered to their Indian captors and were taken on past Detroit with them. Dudley refused to capitulate and made a point of it. When the warrior who had claimed him came to retrieve him, he found out that a ransom had been paid for him by a British major. Dudley was to return to the United States where he would continue on to fight in the Battle of New Orleans in order to avenge the deaths of his fellow Kentuckians who perished in Michigan. At the end of his account, Dudley states,

“Let me here say my Indian captor exhibited more the principle of man and the soldier than all the British I had been brought in contact with up to the time I met Major Muir” (4).

It is with this comment that he acknowledges that there were both good and bad among those who were his captors. Those who were “savages” by the popular opinion of the time showed more humanity than those who were supposed to be “civilized”. Dudley was merely thankful for the chance to survive and return home to his family.

In Closing

Each man involved in the massacre had a different experience and a unique story to tell. Many were not able to tell theirs as they perished on the 22nd of January and would not make it back home to their families. In reading the personal accounts and diaries of the survivors, one can easily see the brutalities of war but also the humanity that can still exist, even among the enemy. For good reason, the battle cry for the rest of the war would remain, “Remember the Raisin!”

Primary Sources

- Dudley, T. (1870). Battle and massacre at Frenchtown, Michigan, January, 1813 (pp. 1-4). Cleveland, Oh.: Western Reserve Historical Society. Battle and Massacre at Frenchtown, Michigan.

- Drimmer, F. (1985). Captured by the Indians: 15 firsthand accounts, 1750-1870 (pp. 256-267). New York: Dover. Captured by the Indians: 15 Firsthand Accounts 1750-1870.

- Darnell, E., & Mallary, T. (1854). A journal, containing an accurate and interesting account of the hardships, sufferings, battles, defeat, and captivity of those heroic Kentucky volunteers and regulars: Commanded by General Winchester, in the years 1812-13. Also, two narratives by men tha (pp. 1-90). Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo.

Secondary Sources

- Grassley, D. (2010). The Battle of Frenchtown. Retrieved October 5, 2015, from The Battle of Frenchtown

- Hansen, Seth (2013). Remember the Raisin!. Retrieved October 5, 2015, from Remember the Raisin!

- Quisenberry, A.C. (1913). A Hundred Years Ago: The River Raisin. Retrieved October 5, 2015, from A Hundred Years Ago The River Raisin.

- Teasdale, Guillaume (2012). Retrieved October 5, 2015, from Old Friends and New Foes.

- Hickey, D. (n.d.). An American Perspective on the War of 1812. Retrieved October 5, 2015, from

An American Perspective[2022: Link dead, but see https://www.pbs.org/show/war-1812/ and on the topic: https://edubirdie.com/blog/history-and-summary-of-1812-war] - War of 1812. (2015). Retrieved December 4, 2015, from War of 1812

Further Reading

- Wikipeda articles on

- A Monroe historical site on the battle

- Massacre at the River Raisin (YouTube)

- The Battle of Frenchtown at the War of 1812 website.

- History.com’s information on President William Henry Harrison