The Wurtsmith Air Force Base a very important air force base in Michigan during Second World War. Renamed Oscoda Army Air Field and containing 3 hard-surface concrete runways, during World War II this base was an airfield for training black aviators and Free French Air Force pilots. After the war, many different squadrons used the air force base, and it was also used to store nuclear missiles during the Cold War. Towards the end of the twentieth century the base was shut down and turned into a landing strip as a transient aircraft stopover. The now decommissioned United States Air Force base is located in northeastern Iosco County Michigan.

Origins

Before this airfield became known as Wurtsmith Air Force Base it was called Loud-Reames Aviation Field. It was built-in 1923 as a soft landing site for airplanes flying from Selfridge Army Air Base near Detroit. They had to fight cold winter days and battle the cold temperatures to get the engines started. To do this, they heated oil over the open fires and then quickly poured it into the engines and started the airplane. From 1924 to 1944 the Air Base was used as an aerial gunnery range and for practicing winter drills. Shortly after it became an aerial gunnery range for one of the first combat air groups the 1st pursuit group, “It was renamed Camp Skeel in 1924, for World War I pilot Captain Burt E. Skeel, and was used as an aerial gunnery range and for winter maneuvers 1924 through 1944 by the 1st Pursuit Group at Selfridge.” [7].

In 1942 when the three hard surface runways were completed, the base was renamed Oscoda Air Force Base. Major General Paul B. Wurtsmith led United States Army Air Corps training flight at Camp Skeel prior to World War II. He was a famous pilot during the war, leading the group of pilots defending Australian cities using P-40 and P-38 fighter aircraft against the Japanese aircraft. General Douglas MacArthur, who commanded the southwest Pacific in World War II, wrote, “Much of our success in the Pacific was due to his brilliant attainments and leadership.”[12]. Wurtsmith became a two star major-general and died in the 1940s in an airplane crash. He was flying a B-25 bomber and even though he was advised by radio from an airfield near Bristol to raise his altitude to avoid the mountains up ahead, he was reported to have said “Who the hell do you think is flying this aircraft!” [4]. Soon afterward, the base was renamed in his honor. Up until 1942 the Air Force base was used as aerial gunnery practice and in early 1943 the base became home for training black aviators during World War II.

World War II

In the 1940s African Americans were still not largely accepted to join the military, but in 1941 a student at Howard University by the name Yancey Williams filed a lawsuit to force the Army Air Corps to accept him into training. The Corps answer was to make a separate unit to train black pilots and grounds crew [16]. During the Second World War the Oscoda Air Force base became home to the infamous fighting unit called the “Black Panthers”, also known as the Tuskegee Airmen. The base the Tuskegee Airmen were originally stationed at was Tuskegee Army Air Field, but they were re-stationed to Selfridge, which they then moved to Oscoda in 1943. One important group there was the 403rd fighter squadron because most of them were combat veterans from the war who came back to help train the 332nd fighter unit.

“Hidden away at Selfridge and a few miles away at Oscoda, are outfits but slightly known, but all are part of the new spirit of the command. “All in all,” said Col. William Boyd, base commander, “I will put them up against any and all comers.” But an important unit here, the supervisory unit, is the 403d fighter squadron, composed of fighters returned from the front. Many of them are heroes, some wearing citations for bravery, and all of them noted for their skill in the air. It is this unit that has been assigned the task of lending personal supervision to the development of the 332d. The 332d considers the presence of the 403d, composed entirely of white comrades of the air, a rich opportunity of their military career.” [10].

The 332d fighter group (the best-known Tuskegee Airmen) at Oscoda Air Force Base consisted of the 100th, 301st, and 302nd fighter squadrons. The group practiced and honed their skills by using P-39s, which were designed in part to strike ground targets on tactical missions. “The group and its 100th, 301st, and 302nd Fighter Squadrons remained at Selfridge from the end of March 1943 to early April 1943, when they moved to Oscoda, also in Michigan. In early July, the group and its squadrons moved back to Selfridge where they remained until the end of the year. During its time at Selfridge and Oscoda in Michigan, the 332d Fighter Group honed its skills with fighters designed in part to strike ground targets on tactical missions, including P-39s that it would use after deployment overseas.”[8]. After they completed their training in 1944, they were deployed overseas and flourished in battle. They did bombing runs in many regions such as Normandy, France, Rhineland, Central Europe, and during World War II they were credited with 111 Aerial victories [3]. They ranged from navigators, bombardiers, mechanics, instructors, crew chiefs, nurses, cooks, and more. The Tuskegee airmen were the first African-American aviators in the United States Armed Forces and during the war they were assigned missions for escort missions for heavy bombers (179 bomber escort missions, losing only 27 bombers). Benjamin Oliver Davis, Jr. who was the commander of the 32nd fighter group became the first African-American to become a General in the Air Force [9]. After the 332nd fighter group left Oscoda Air Field in 1944, the base then became home for training Free French Air Force pilots.

In May-June 1940 the last of the British and French troops evacuated from Dunkirk, France. The British War Office wrote “Up to 30th May, 1940, the arrangement was that British troops were to be taken off in British ships and French troops in French ships. Notwithstanding this arrangement up to noon 31st May 14,811 French troops in addition to 149,342 British had arrived in this country in British ships. The number taken off in French ships is not known but the Admiralty had the impression that the French navy made very little effort and that no effective steps had been taken to collect French coastal shipping.” [1]. With the fall of France in 1940 the remaining French forces retreated to countries overseas. Now having lost their air force bases in France, some of the Free French Forces had to use Allied controlled air force bases to train the Free French Air Force pilots.

Originally stationed at Blackstone Air Force Base in Virginia, the 134th Army Air Force Base Unit transferred to Oscoda Army Air Field. One French lieutenant, 34 students, and nearly all of the people from Blackstone Army Air Force trained there. Almost doubling the amount of personal on the base that peaked at 3,500 people. “Under this new setup, the 134th AAF Base Unit (Fighter) consisted of four sections: Medical, Supply, Administrative, and the French group. A training program was set up that consisted of subjects designed to prepare personnel for shipment to combat zones. Subjects ranged from gas warfare to first aid, and classroom instructed was supplemented by field exhibits, movies, and lectures.” [5]. After that the pilots were trained in rigorous advanced aerial training, and then sent to Washington, D.C to be deployed abroad.

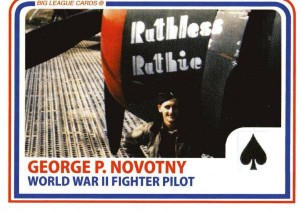

After his tour in Europe a pilot and ace by the name George P. Novotny became an instructor pilot and trained the Free French Air Force pilots at Oscoda until the end of the war in 1945. In Europe he flew the P-40 Warhawk, the P-47 Thunderbolt, and the P-51 Mustang and was credited with 8 aerial victories. George Novotny’s favorite airplane was the P-47 Thunderbolt saying how he thought it was the superior one “The way it usually worked was that the P-38s went out with the bombers and the P-47s brought them home when the lightings left, low on fuel. I loved the P-47. I’d always had the feeling that we were flying “defensively” during our P-40 period, but with the P-47, that feeling went. We could do some real damage with that aircraft, and with 165 gallon tanks, we could stay up for a good 6 hours.” [14]. Although most trained at Oscoda Air Force Base used P-39s, they also used the P-47s. The Free French Air Force also trained in B-26 bombers here at Oscoda Army Air Field, and used them over sea in the war. They flew 627 missions with the B-26 bombers, and dropped over 7 thousand tons of bombs [15]. In late months of 1944, 125 men received gunnery training and 93 French Airmen completed their training. Mainly flying in Africa and the Western Front, they had 344 plus aerial victories; with another 46 possible, 97 damage, 104 vessels sunk, set on fire or damaged, and hundreds of vehicles, locomotives and equipment of all kinds destroyed on all fronts [10]. With the end of the war on the second of September 1945, training officially ended for the Free French Airmen at Oscoda Air Force Base.

After World War II

The end of the Second World War officially ended the training of Free French pilots at the base. The base was then used as a bombing and gunnery range by Selfridge Army Airfield. The base then became a fighter-interceptor training base for the Air Defense Command in January of 1951. A lot of construction was done to update the old base to the new standards. After that it was home to the 63d Fighter-Interceptor Squadron (May 1951), the 412th fighter group, the 445th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron, the 31st Fighter-Interceptor Squadron (June 1956), the Strategic Air Command’s (August 1958), then Strategic Air Command’s again in (1959). The Strategic Air Command’s once reactivated at the Air Force Base, was assigned to the Eighth Air Force and it was to supervise and monitor the operation of the 379th and 410th Bombardment Wings, the 305th Aerial Refueling Wing, the 351st Strategic Missile Wing, the 128th Aerial Refueling Group, and the 931st Aerial Refueling Group. In 1993 the base closed and the airfield became an airport called the Oscoda-Wurtsmith Airport. [13]

Primary Sources

[1] J. Scutts, P-47 Thunderbolt aces of the Ninth and Fifteenth Air Forces. Oxford: Osprey, 1999.

[2] Larsen, Deborah J., and Louis J. Nigro. “Camp Skeel Picture.” Selfridge Field. Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2006. 52. Print.

[3] R. Simmons, ‘Moral Chief Spurs Colored Selfridge Unit’, Chicago Daily Tribune, p. NW7, 1943.

[4] Blue Ridge Outdoors Magazine, ‘Mayday! Hiking to Plane Crash Sites in the Southern Appalachians’, 2009. [Online]. Available: http://www.blueridgeoutdoors.com/hiking/mayday-hiking-to-plane-crash-sites-in-the-southern-appalachians/. [Accessed: 18- Nov- 2015].

[5] Wafb.net, ‘WAFB.NET Database Driven Menubar (Cross Frame)’, 2015. [Online]. Available: http://www.wafb.net [Accessed: 18- Nov- 2015].

[6] Nationalarchives.gov.uk, ‘The National Archives Learning Curve | World War II | Western Europe 1939-1945: Invasion | How worried was Britain about invasion 1940-41?’, 2015. [Online]. Available: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/worldwar2/theatres-of-war/western-europe/investigation/invasion/sources/docs/2/transcript.htm. [Accessed: 17- Nov- 2015].

Secondary Sources

[7] Haulman, Daniel L. “The Tuskegee Airmen and the “Never Lost a Bomber” Myth.” Alabama Review 64.1 (2011): 30-60. TUSKEGEE AIRMEN CHRONOLOGY.

[8]J. Caver, J. Ennels and D. Haulman, The Tuskegee airmen. Montgomery, AL: NewSouth Books, 2011.

[9] “Benjamin Oliver Davis, Jr., General, United States Air Force.” Benjamin Oliver Davis, Jr., General, United States Air Force. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 Nov. 2015. <http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/bodavisjr.htm>.

[10] Everworld.com, ‘332d Fighter Squadron’, 2015. [Online]. Available: http://www.everworld.com/tuskegee/332d_fighter_squadron.htm. [Accessed: 17- Nov- 2015].

[11] Wikipedia, ‘Tuskegee Airmen’, 2015. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tuskegee_Airmen. [Accessed: 17- Nov- 2015].

[12] Placeandsee.com, ‘Wurtsmith Air Force Base’, 2015. [Online]. Available: http://placeandsee.com/wiki/wurtsmith-air-force-base. [Accessed: 17- Nov- 2015].

[13] Wikipedia, ‘Wurtsmith Air Force Base’, 2015. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wurtsmith_Air_Force_Base. [Accessed: 17- Nov- 2015].

[14] Charles-de-gaulle.com, ‘The Free French Air Forces’, 2015. [Online]. Available: http://www.charles-de-gaulle.com/the-warrior/free-france/the-free-french-air-forces.html. [Accessed: 18- Nov- 2015].

[15] Axis History Forum, ‘The (Free) French Air Force in 1940-1945 (Listing attempt) • Axis History Forum’, 2015. [Online]. Available: http://forum.axishistory.com/viewtopic.php?t=98874. [Accessed: 18- Nov- 2015].

[16] History Net: Where History Comes Alive – World & US History Online, ‘Tuskegee Airmen’, 2015. [Online]. Available: http://www.historynet.com/tuskegee-airmen. [Accessed: 19- Nov- 2015].

[17] “Factsheets : Former Wurtsmith Air Force Base History.” Factsheets : Former Wurtsmith Air Force Base History. N.p., n.d. Web. 08 Oct. 2015. http://www.afcec.af.mil/library/factsheets/factsheet.asp?id=20104

[18] Sheppard, James A. “BLACK AIRMEN IN WORLD WAR II.” BLACK AIRMEN IN WORLD WAR II. N.p., n.d. Web. 05 Oct. 2015.http://www.bjmjr.net/ww2/black_airmen.htm

[19] “Wurtsmith Air Force Base Historical Website – WAFB.NET.” Wurtsmith Air Force Base Historical Website – WAFB.NET. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Oct. 2015. <http://www.wafb.net/>.

[20] Sammcgowan.com, ‘Tuskegee Airmen’, 2015. [Online]. Available: http://www.sammcgowan.com/332nd.html. [Accessed: 12- Dec- 2015].