In June 1812, the United States’ feud with Great Britain reached a high point and the two countries plunged into war. Heat from the previous war between the two only made the situation more likely to turn to war in the United States once again. Great Britain’s dislike for the young and newly created United States caused them to employ various trade restrictions that damaged the trade between the United States and other European countries. More specifically, Great Britain’s war with France, prior and during the War of 1812, caused them to force unfair trade restrictions that hurt the United States’ trade with France. Great Britain also used the act of impressment to illegally force United States seamen and merchant sailors into the Royal Navy, Great Britain’s impressive and world leading navy. Great Britain’s support of American Indians also caused anger in the United States when Great Britain proposed to support the Indians with military supplies, including weapons, so they could stop the United States’ expansion into the western and north western regions of the United States. This last issue comes into play when the War of 1812 begins. The forces of Great Britain were enhanced by thousands of Indian allies that backed the supportive British and not the United States. One British General, Henry Proctor, had many Indian allies and used them while operating in the Detroit frontier to help the British succeed at Frenchtown.

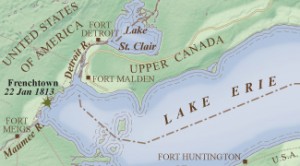

As the War of 1812 progressed, three theaters formed around the United States. The theater in the Atlantic bout the two countries navy’s against each other. The theater in the South and Gulf Coast only resulted in minimal fighting and relatively unimportant battles. Finally, the theater in the North, also called the Great Lakes Theater, is where most of the brutal fighting and strategic gains occurred. Fighting in the northern theater didn’t just include fighting in the United States but also fighting in Canada. Great Britain had forces in Canada and at the beginning of the war had them head south into the United States. One of the ways you can get into the United States from Canada is by traversing the St. Lawrence region between Lake Erie and Lake Huron. This can lead you into two states depending on the direction you go. Heading East is New York and is where many British Soldiers went but heading west will take you to the Detroit frontier into the Michigan Territory. The Detroit frontier is where General Henry Proctor, his British Soldiers, and his Indian allies concentrated most of their fighting.

The Detroit frontier which included Fort Detroit (located on the Detroit river in Michigan) and Fort Malden (located on the mouth of the Detroit river in Canada), were crucial and strategic forts for both the British and the United States. For the British, these forts stood as gateways into the United States for British troops stationed in Canada. One of the overall strategic plans of the British was to use their forces in Canada to invade the United States from the north. Controlling these two forts would make the invasion of the United States much more efficient for the British. British supplies could be easily transported down the Detroit River from more northern regions of Canada as well. For the Americans, these forts were necessary for the defense of the British invasion through the northwest regions of the United States.

At this point in the War of 1812, both the British and the United States wanted control over the Detroit frontier and an inevitable theater was about to progress. Fort Detroit was lost by the Americans when the British used their devastating siege warfare on the fort in the summer of 1812. The British, led by General Brock, easily destroyed the United States forces defending the fort. This then started the aggression between the United States and the British in the Detroit frontier. In the Detroit frontier is where British General Henry Proctor was assigned to do his duty in the War of 1812 by ranking General Brock. Proctor had little practical experience and mostly had theoretical knowledge of warfare but was given command of Fort Malden. His main objective was to defend the fort from the Americans after the old commander of Fort Malden was relieved. American forces led by, General William Henry Harrison, sought to rid the British from Michigan and stop their advance into the United States.

Prior to this point in the war, the British had full control over the settlement at Frenchtown which lies on the Raisin River. On January 18, Frenchtown was lost when a detachment of American forces went and relieved the settlement from the small force of British and Indian troops that occupied it. American forces were led by Colonel Lewis who went by his superiors order to save the settlement of Frenchtown. Colonel Lewis was a detachment of Brigadier General James Winchester’s forces that were deployed in the northwestern region of the United States in the Detroit frontier. Brigadier General James Winchesters main objective was to retake Fort Detroit from the British. Winchester was aided in retaking Fort Detroit by General William Henry Harrison. On their way to Fort Detroit, Winchester decided to send aid to Frenchtown even though it was against direct orders from Brigadier General William Hull who was the commanding general of the northwest. Winchester sent Colonel Lewis to retake Frenchtown. Frenchtown wasn’t as an important strategic settlement as Fort Detroit or Malden, but served as a stepping stone for the United States to reach both of the forts. Colonel Lewis’ retaking of Frenchtown from the British and Indian occupancy was considered the first battle of Frenchtown and would led to much more distress in the next couple days.

News of the loss of Frenchtown arrived to General Henry Proctor at Fort Malden, also known as Fort Amherstburg, in Ontario, Canada. Proctor gathered a combination of 597 British regulars, 6 cannon, and 800 Indian allies led by Chief Roundhead and headed to retake the settlement of Frenchtown. General Proctor’s alliance with the Native Americans of the region was an essential strategic move that helped the British at Frenchtown. Chief Roundhead and Walk-In-Water, the two Native Americans in charge of the military alliance of the British and Indian tribes of the Miami, wrote a letter to the British stating a strong ultimatum. It read,

The Hurons, and the other tribes of Indians, assembled at the Miami Rapids, to the inhabitants of the River Raisin. –Friends, Listen! You have always told us you would give us any assistance in your power. We, therefore, as the enemy is approaching us, within 25 miles, call upon you all to rise up and come here immediately, bringing your arms along with you. Should you fail at this time, we will not consider you in future as friends, and the consequences may be very unpleasant. We are well convinced you have no writing forbidding you to assist us. We are your friends at present.

Signed

Roundhead(his mark)

and Walk-In-Water(his mark)

As it clearly states in the letter, the Indian tribes of the area were forcibly asking the British to help them as the American forces closed in around the land of the Indians. The Native Americans wanted to stop the rapid expansion of the United States and couldn’t fend for themselves. By asking for aid from the British, this could be done. With this letter, the British forces of General Brock, and more specifically General Proctor, happily allied with Chief Roundhead and Walk-In-Water. The British realized that it was better to have allies in the area then create hate between them and the Native Americans. With this alliance, many Indians joined the forces of General Proctor to help take back the settlement of Frenchtown.

Winter is upon the forces of British Brigadier General Henry Proctor as he leads his troops over the frozen Detroit River headed toward the American settlement at Frenchtown. Proctor took use of the frozen Detroit and Raisin rivers to move troops and artillery to Frenchtown in an efficient manner. The night of January 21, Proctor assembled his troops and artillery only five miles from the Frenchtown settlement. The small number of troops and his movement at night helped Proctor get into very close range to Frenchtown. Also, an unprepared and over-confident Winchester had his forces spread throughout Frenchtown and wasn’t suspecting British retaliation for “some days.” Proctor had a numerical advantage and went unnoticed by the enemy until Americans spotted cannons being set up before the attack. At that point it was too late for the Americans. It is said that Winchester was “awakened by artillery fire and Indian screams on the morning of the battle” and was extremely unprepared for such an attack. Proctor started with a typical, but effective, artillery barrage of Frenchtown with six small cannon. He then commanded his Indian allies to flank the Americans and cut off any routes of escape from Frenchtown. With Frenchtown surrounded, the British and Indian allies won this battle.

The absolute destruction of American forces gave the British a significant victory in the Second Battle of Frenchtown. Americans suffered 500 dead, 60 wounded, and 500 captured by the British and Indians. Only 24 British were killed with 158 wounded. The huge difference in numbers came from good strategic positions and strong tactics from Proctor. His quick and unnoticed movement within five miles of Frenchtown gave him and his men a strategic advantage. Tactical use of cannons to weaken fortified enemy riflemen made it so Proctors troops could advance towards Frenchtown and use of a flanking maneuver of his Indian allies made for a decisive victory. Proctor did make a mistake by placing his artillery too close to the settlement, as his cannons were in range of American riflemen and many casualties resulted from this error.

Even though the battle was a total victory for the British, Proctor wisely chose to head back to Fort Malden with the captured Americans. This was a very smart move on Proctor due to the fact that he knew a larger force of Americans would be headed to take back Frenchtown. He did not have the forces to defend the settlement and keep control of 500 prisoners.

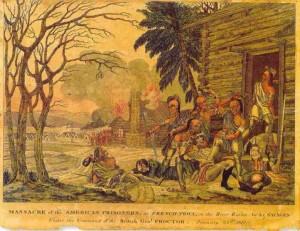

Before heading back to Canada, Proctor decided to leave the injured prisoners because there were just too many to transport back to Fort Malden. This lead to the River Raisin Massacre where it is said Proctor left injured prisoners and alluded to his Indian allies to kill them after they had gone. The Indian allies killed 30 to 100 injured prisoners and citizens at Frenchtown for revenge on Indian brothers lost in the prior days fighting. After the battle and massacre a letter was written to Samuel Bayard from Senator James Bayard that said of about the one thousand American forces at Frenchtown, only about forty of fifty escaped after the events that happened on the twenty first of January.

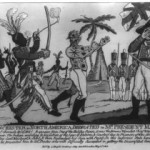

Winchester’s defeat was not a battle lost where two sides fought hard and long until a victor arose. This was an embarrassing situation for the United States and more specifically General Winchester. Winchester’s unpreparedness of his soldiers and of the defense of Frenchtown made it an easy victory for the British and Indians. The embarrassing stories of how Winchester was “woken by artillery” and how he “ran to battle in sleep attire” proved to be the least of his worries. Many depictions of Winchester were laid out in illustrtions of him and his unpreparedness at Frenchtown. The one to the right depicts a unprepared Winchester being “forced” around by a Native American who is clearly in charge with sword drawn and pipe lit. This is also embarrassing because Native Americans were seen as lower beings to the Americans making this painting worse for Winchester’s reputation. General Proctors amusement of Winchester being messed with by the Indians is also seen in the cartoon.

Proctor had a strong and decisive victory both strategically and tactically due to various factors and his leadership abilities. Events such as the massacre (and Proctors supposed involvement) as well as other “unmoral” things he did, marked him as one of the worst British Generals in the War of 1812. None-the-less, he made smart tactical decisions during the Second Battle of Frenchtown that created a victory for his men and Britain.

Primary Sources:

- Bayard, James. “The “River Raisin Massacre”” Letter to Samuel Baynrd. 9 July 1813. MS.

- Chief Roundhead, and Walk-IN-Water. Letter to Henry Proctor. N.d. MS.

- A View of Winchester in North America. 1813. Library of Congress, n.p.

Secondary Sources:

- Grassley, Dave. “The Battle of Frenchtown.” The Battle of Frenchtown. Floral City Images, 2010.

- Hammack, James Wallace, Jr. “Kentucky and the Second American Revolution.” The University Press of Kentucky

- Hickey, Donald R., and Walter R. Borneman. “River Raisin National Battlefield.“

- Ridler, Jason. “Proctor, Henry.” War of 1812. The Royal Canadian Geographical Society

For Further Reading:

- “Henry Proctor.”Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation

- “Siege of Detroit.”Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation

- “War of 1812.”Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation

- Jones, Nick. “Tactics of the Battle of the River Raisin.” Military History of the Upper Great Lakes

- Shuler, Carrie. “The River Raisin Massacre.” Military History of the Upper Great Lakes

- Carey, Grace. “General Winchester: 1813.” Military History of the Upper Great Lakes