On December 29, 1940, roughly one year before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Franklin D. Roosevelt gave a speech vowing to aid the Allies in their fight against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan by providing military supplies while staying out of the actual conflict. In order to do this, all war materials, such as tanks, planes, and guns would be manufactured in American factories, therefore outlining his concept in the “Great Arsenal of Democracy” [1]. The enrollment of American manufacturing in the Second World War was filled with the idea of mass production, a concept made popular by Henry Ford. One of the most prominent factories that used the idea of mass production was B‐24 bomber plant at Willow Run Airfield in Michigan. Started by Ford himself, the plane and the manufacturing of the planes was the perfect example of American productivity during the Second World War. However, by the time the U.S. entered the war, Henry Ford was a paranoid eccentric who was very skeptical about actually fighting the war, and had become estranged from his son who actually operated the plant. However, despite all of the problems within the actual family, the Ford family helped to create one of the most powerful aircraft factories in America’s Arsenal of Democracy, which in turn brought the US to victory in World War II.

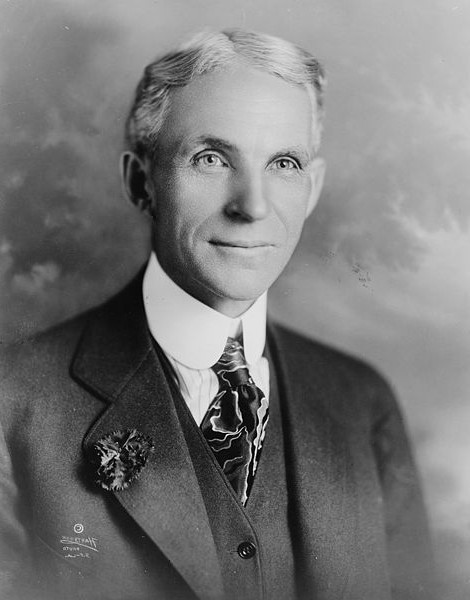

Henry Ford and the Plant’s Beginnings

To meet the challenge of President Roosevelt ordering factories to make greater numbers of aircraft, Henry Ford was determined to create the largest aircraft factory in the world. While he was definitely the giant of automobile mass production, “he saw little difference between one manufactured article and another” [6, p. 149]. Willow Run Airfield, at first an insignificant shell of what it would become, turned out to be a miracle, producing one bomber every hour.

What is ironic about Willow Run’s beginnings is that the property where it would have its origins was built on was a very quiet and peaceful plot of land: it was the farm where Henry Ford grew apples and soybeans. Many years before the construction began, Henry built a summer camp for boys known as Camp Willow Run, named after the creek that ran through the fields.

Ford initially did not embrace the project with open arms, as in his eyes, it made no sense to tear up his farm and orchard to build a factory that would help in a war that did not appear to affect the US. Honoring his isolationist beliefs, Ford declined to help produce airplane motors for Great Britain and even forced his son Edsel to cancel “the production of 6,000 Rolls-Royce engines for Great Britain, and 3,000 of the same type for the United States” [2]. To support his belief that the United States was in no danger, Henry Ford stated on May 28, 1940 that if in the event that the war did come close to threatening the US, his company could, under the control of him and his staff, and no interference from government agencies, “swing into the production of a thousand airplanes of standard design a day” [6, p. 149]. However, as the need for military supplies increased, public opinion eventually forced Ford to come to an understanding to manufacture planes for the United States. Ground was broken for the plant on April 18, 1941, and the resulting factory was one the largest factories in not just the US, but the entire world, occupying a space of more than four million square feet and a government investment of nearly $100 million.

Despite the fact that his company had successfully opened up the bomber plant that became part of the arsenal of democracy, there is evidence of connections between Henry Ford and the Nazis. In 1919, Henry Ford began writing a series of anti-Semitic pamphlets called The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem, which was published in ninety-two issues of the Dearborn Independent newspaper [8]. This was greeted with much chagrin from Edsel, who had many close friends that were Jewish. In 1922, the pamphlets were all published into a book of the same name. The book had an avid audience in Germany, and among the biggest fans was a young Adolf Hitler who kept a copy of the book in his office, “as well as a portrait of Henry Ford” [12, p.34]. Hitler used Ford’s writings to help promote his anti-Semitism to the German people when he came to power in 1933 [12, p.146]. In 1938, Hitler “made a public statement about his admiration for Henry Ford.” He even went so far as to have German officials present Henry with the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, the highest award offered to a non-German, as well as sending a note to thank Henry for his charitable standards. “Henry refused to give the award back,” [12, p.34] possibly to avoid angering Hitler.

Edsel Ford: The Operator of the Arsenal of Democracy

Unlike his father, Henry, Edsel Ford “was gentle, considerate of others, unsparing of himself — and he was a man” [3]. He joined his father’s business after graduating high school, becoming its president in 1919 at the age of 25 [10]. As president of the company, Edsel coordinated a decision-making group headed by his best friend, Ernest Kanzler. Despite having responsibility, he did not officially have power over the company, and his father was so estranged that they could not speak to each other. When Kanzler wrote a message to the elder Ford in regards to creating a new car model, he was fired. Henry became increasingly more suspicious of his son, and even resorted to paying his son’s employees to spy on him.

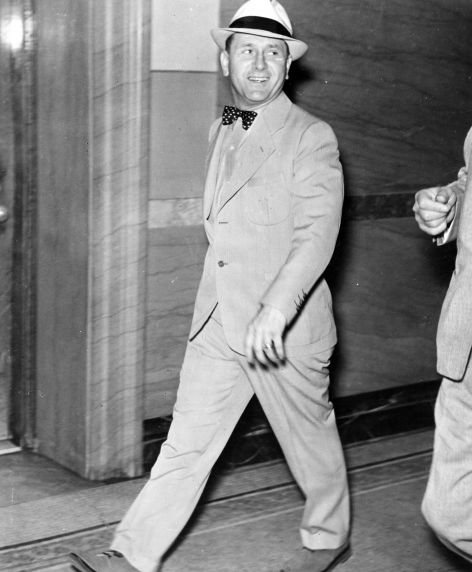

To make matters worse, his father had also hired a former Navy sailor and boxer named Harry Bennett as a new executive. Bennett, whom his father encountered after witnessing Bennett street-fighting in New York, soon became “the auto tycoon’s right-hand man” [13]. He used Bennett to help break up unions, often using underground connections and even through violence. Bennett soon assembled the Service Department, a group of ruffians and criminals which later became Ford’s private security force. By 1937, the Service Department had roughly 800 men and became known as, according to H. L. Mencken’s American Mercury magazine, “the most powerful private police force in the world” [7, p. 150].

But if there is anything that Edsel Ford did share with his father, it was a fascination with airplanes and they both saw huge potential for use in combat. In May 1940, Edsel visited Washington to “attend meetings about aircraft production” [12, p.78]. On the day that Edsel arrived in Washington, hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers were being evacuated by ship from Dunkirk, France, beaten back by German troops. This caused a lot of fears of a possible German invasion of Great Britain. Edsel, in contrast to his father, was a friend of President Roosevelt. Wanting to help the Allies, Roosevelt issued out the Lend-Lease Act, which provided supplies to the war effort without getting involved in the actual fighting. Among other things, Roosevelt “promised thousands of aircraft engines to the British” [12, p.78] and they had to be manufactured quickly. Edsel Ford agreed to help. The following month, Edsel and his executive, Charles Sorensen, discussed a deal for 9,000 aircraft engines (one-third would go to the US military, while the British would take the remaining two-thirds). At first, his father seemed to be on board with the idea, but two days later, he changed his mind and forced his son to cancel, fearing Roosevelt was trying to bring the US into the conflict. Combined with his anti-Semitism and his Nazi medal, this further convinced the public that Henry had Nazi sympathies.

On the week following Roosevelt’s “Arsenal of Democracy” speech, Edsel, his sons Benson and Henry II, both college graduates, and a few of his staff members visited the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation factory in San Diego, CA and saw their first B-24 Liberator bomber. Edsel toured the aircraft and realized that this bomber was indeed a powerful tool of war. The downside, however, was that the aviation firm lacked the production capacity. Edsel’s response to this was to make the bombers the same way that they made automobiles: through mass production. The result was the Willow Run Airfield.

During this time, Henry Ford met with the famed Aviator Charles Lindbergh to discuss opposition to the war effort. Much like Ford, Lindbergh was awarded the Grand Cross of the German Eagle and had a close connection with Germany. He had an extensive amount of knowledge in regards to the Luftwaffe and had even flown some of their planes. His reason for staying out of the war was that he believed the American and British air forces were inferior to the German, and would not stand a chance. Ultimately, this would end up leading to an investigation of the plant for possible treason later on. Everything changed, however, when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor.

After the attack, the number of workers at Willow Run increased dramatically. Knowing the critical task of providing much-needed aircraft to the Allies, Edsel concentrated all of his energy into the plant. He even went so far as to negotiate a communication line into Nazi-occupied Europe to make sure his executives were safe. It was during his time operating Willow Run that Edsel had been suffering from abdominal pains for a number of years. Medical doctors discovered that this was caused by tumors in his stomach and warned him that going back to work could endanger his life. In the year 1943 alone, more than 7,000 bombers took off from the airfield, each one needing test flights and checkoffs before being delivered to the Army. The man in charge of making the test flights was none other than Lindbergh himself, who claimed earlier that German air power was superior to Allied air power. His close relationship with Germany made him unable to get a military command, so the Army requested him to “begin a series of high-altitude flying experiments” [12, p. 203]. Edsel successfully nurtured the bomber plant to the point where it was nearing its full potential. Tragically, he would not live to see it; on May 26, 1943, he finally succumbed to his stomach cancer at the age of 49.

Henry Ford II Faces the Bully

The death of Edsel Ford left his father Henry devastated. Six days afterward, Henry Ford announced to the board of directors for Ford Motor Company that he would return to being president of the company, much to the disdain of Edsel’s family and closest staff members. Even President Roosevelt was concerned about the company. Henry was in no condition to run such a large company with a critical mission. Ultimately, the decision was made: to pull his grandson, Henry II, out of wartime service and have him take over.

Henry II had his work cut out for him. Under the direction of Edsel Ford’s executive, Charles Sorensen, the production of the company received much acclaim from Washington. But despite the accomplishments, if Willow Run did not have a proper leader, everything would fall apart. In order to avoid the wrath of Harry Bennett and the Service Department, several of the company’s top engineers left. It was here that Henry II found his first task: to get rid of Harry Bennett, the street-fighting thug used by Henry Ford to break up unions.

Following the German surrender, the last B-24 Liberator, which was named the Henry Ford, left the factory at the end of June. Three months later, after the Japanese surrender, Henry Ford II was named the president of the company by the board of directors. Willow Run’s wartime service was finally complete. Even with all of the problems within the Ford family, the manufacturing complex at Willow Run Airfield became one of the most powerful aircraft factories in the great American Arsenal of Democracy.

Primary Sources

- Roosevelt, Franklin D. (1940). The Great Arsenal of Democracy. Radio broadcast, Washington, DC.

- The Associated Press. (1947) “Henry Ford Is Dead at 83 in Dearborn.” The New York Times

- Sorensen, Charles E. and Lewis, David L. (2006) My Forty Years with Ford. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- Nevins, A., & Hill, F. E. (1963). Ford: Decline and rebirth, 1933-1962. New York: Scribner.

- Lindbergh, Charles (1970). The Wartime Journal of Charles A. Lindbergh. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich

Secondary Sources

- Ferguson, Robert G. (2005) “One Thousand Planes a Day: Ford, Grumman, General Motors and the Arsenal of Democracy.” History and Technology 21.2: 149-75.

- Wallace, Max (2003). The American Axis: Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh, and the Rise of the Third Reich. St. Martin’s Press

- Ribuffo, L. P. (1980). “Henry Ford and the International Jew.” American Jewish History, 69(4), 437–477.

- Wrynn, V. Dennis (1993). Detroit Goes to War: The American Automobile Industry in World War II. Minneapolis: Motorbooks International

- Dominguez, Henry (2002). Edsel: The Story of Henry Ford’s Forgotten Son. Detroit: Society of Automotive Engineers

- Hyde, Charles K. (2014) “Arsenal of Democracy: The American Automobile Industry in World War II.” Choice Reviews Online 51.09

- Baime, A. J. (2014) Arsenal of Democracy: FDR, Detroit, and an Epic Quest to Arm an America at War. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Further Reading

- Wilson, Amy. (2003) “The Rise and Fall of Harry Bennett.” Automotive News.

- Smith, Scott S. (2015)”Edsel Ford Built the Bombers That Paved D-Day’s Way.” Investor’s Business Daily.