Sparta, Michigan is considered one the most fruitful apple cities in the country. Lesser known is their involvement in World War II as a host of a POW Camp in 1944. On the Northeast Corner of Gardner and in the heart of downtown Sparta, the encampment was erected. This camp was set up for POW’s to be employed as laborers during the harvest season- picking mostly apples along with cherries and various vegetables.

Michigan Prisoner of War Camps

During the war, taking soldiers as prisoners was no task left for those abroad. Back in the mainland, the United States were building posts for these POWs. Over 15 thousand Axis prisoners were brought to Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan with “about 60 per cent of the prisoners performing contract labor outside prisoner of war compounds . . . engaged in agriculture, fruit, and vegetable harvesting” [10]. While not all of these camps can be considered luxury, many served purposes and helped the common public. In Michigan, several camps were erected for the purposes of picking fruit and helping farmers continue their harvest in the midst of the war. Because of the Selective Service and Training Act of 1940, “over 5.5 million men, 18 through 37 years of age, were examined” to be registered for the military [10, pg 1]. After the United States entered the war, many young men who were previously working on the farm were shipped off to fight for the greater cause of their country. This left a huge labor hole in Michigan farms. Farmers who felt this hole and wanted to use POW labor “had to apply for it through the government. . . [and] banks would loan money to farmers for POW service” [8, 2013]. There was an underlying motive by the government through the use of the camps along with the basic labor need. Tomas Jahen in a report regarding the prisoners in the Midwest stated that “employment of POW labor in shorthanded industries could release troops and civilians for other work more directly related to the war effort” [9, pg 47]. In the quiet town of Sparta, located in the heart of the Bible Belt of Michigan, such a camp arose.

The Kraft Farm and Sparta’s Response

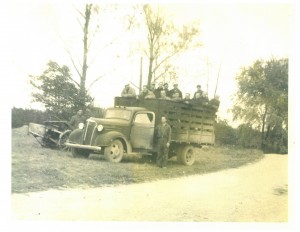

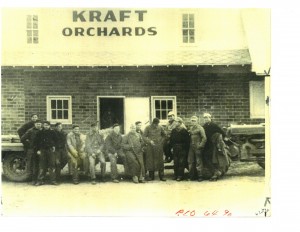

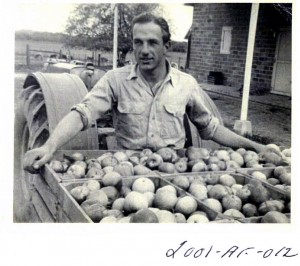

Kraft Orchard, located on the outskirts of Sparta along Fruit and Peach Ridge, was host to prisoners at the time. The Kraft families sent their own boys off to fight in the war and, thus, were in dire need of harvesters for the upcoming season. Apples have been and, as long as the soil remains fertile, will always be a major economic benefit towards the Spartan community bringing income to not only the family farm, but also into local Sparta businesses. When the local growers realized their lack of labor, the Growers Association of Kent, Ottawa, and Muskegon County met to decide their plan of action. Two options were proposed at their annual business meeting: 1) hire local schoolkids from junior and senior high or 2) utilize enemy prisoners [7, pg 2]. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers were already in the United States at the time and nearly 10,000 of these prisoners were located in Michigan. Option 2 passed with a unanimous vote of the 200 orchardists.

The Sentinel Leader, the local newspaper in Sparta, wrote in their weekly paper about the upcoming events: “Sparta being the center of labor needs was chosen as the suitable site to erect the camp” [2, 1944]. By early September, a winterized camp was set up in downtown Sparta adjacent to the usual hustle and bustle of the small town. The POW’s were paid 10 cents a day for working a 7-5 day Monday through Friday in the orchards. Escape was not a fear for the keepers of the prisoners and many stated that “it’s not the guards or snow fence that keeps us in- it’s the Atlantic Ocean” [7,pg 3]. The prisoners created their own system of discipline with intervention of outsiders was rare.

Merlin Kraft was a field-hand during the time and was on agricultural deferment from the draft to help his parents and grandparents with the upcoming harvest at the Kraft Farm. After working with the prisoners he found out just what they were:

We found out that they represented the hated Nazis the killers of millions of people. In reality, they were family men; husbands, fathers, brothers, boyfriends, home-sick boys thousands of miles from home some admitting they cried themselves to sleep at night. . . . [1, 1996].

After the community realized that some of the soldiers were caught up in the situation of their country that they can only roll with, they began to sympathize and relate to them. Merlin became well-versed with the soldiers on a day-to-day basis and spent much time with Roland Detshel who was considered the head prisoner. Detshel informed Merlin that “when they [Germany] won the war, he would ask for our farm and I [Merlin] could work for him” [1, 1996]. Clearly, this shows a friendship between the two men rather than animosity. Continuing with the work throughout harvest, the prisoners and workers became more as companions rather than enemies. At the time of Heindrich Feldmen’s, a prisoner, birthday, Mrs. Kraft baked him a birthday cake along with his usual hot dinner and a small gift. She “stuck it in the cake so he found it when he served it to his fellow prisoners” [1, 1996]. A week later, Feldmen presented Merlin’s dad with a silver ring crafted out of the coin he received.

Needless to say, the town was grateful that the precious fruit was being harvested on time and didn’t think too much about who was particularly harvesting it. The Spartan community reacted in a kind manner to the arrival and keeping of the soldiers. A County Farm Agent wrote in the local newspaper, “the prisoners of war have helped materially with plenty of the other farm work. . . This group of prisoners have been good to work with” [3, 1944]. The prisoners were treated kindly by the community and kept on their best behavior. Some of the soldiers kept in contact with Mr. and Mrs. Kraft. Karl Heinz Kleff, a prisoner who was known for his singing in the camp, sent a letter to Mrs. Kraft regarding his state of affairs and continually wished the Kraft family the best:

Very Honored Mr. Kraft,

Best greetings from my home sends you Karl Heinz K. . . . first of all I [would] like to know how you are. I wish you the best. Hope you are all well. I also [would] like to know how Merlin is, and if he came back allright from this War? I like to think back on the nice time we could spend on your farm. . . . [5, 1946].

Karl also expressed need in his letter and asked if Mrs. Kraft could send him a gift basket to help him and his family eat and survive the battles they were currently facing in their town:

. . . Now[,] dear Mrs. Kraft I [would] like to ask you a favor. I would be very thankful if you could send me a gift package to help us a little out. Life is no fun if you have nothing to live on. . . . [5, 1946].

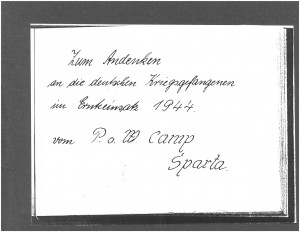

With this exchange of words, it is obvious to see that while the workers on the farm were enemy soldiers, they became so much more to those around them. Mrs. Kraft sent many gift baskets and many letters were exchanged between the two. When the camp closed in 1944, the local farmers “have been well satisfied with the prisoners’ work, explaining that they have harvested crops which might have otherwise have been damaged by freezing weather because of the labor shortage” [4, 1944]. Merlin Kraft kept an “old autograph book with the names and addresses of those prisoners who worked for him” [7, pg 6]. This example of keeping a momentum of the prisoners illustrates the continued idea that the prisoners were seen as people by the surrounding community and treated as such.

German Soldiers at the Camp

The average prisoner in the Spartan camp was between the ages of 20 and 22 and had been captured in the African campaign. They were a part of the tank corp. under General Irwin Rommel. Merlin stated that “the P.O.W.’s seemed to adore him almost as father-figure and his name came up often in their conversations [1, 1996]. Many were pro-Third Reich and believed and hoped Hitler would win the win. As were many in the camp, soldiers like Roland Detshel were Hitler’s Children. Hitler’s Children were children plucked from their parents at young age to be brought up in the Nazi doctrine. These children that the Nazi Party felt were pure enough in blood lines to sire the so-called Super Race [1, 1996]. Merlin stated that Detshel was proud to be a part of the Children and Kraft would say he was brain-washed. Such brainwashing began at a young age where the children were taught to “condemn everything known in Western Europe and the United States as ‘liberalism’” where Hitler expressed that the “object of our education is to produce the political solider” [6, pgs 442 & 444]. Detshel was merely a reflection of his education and, while he was continually told about the evils of the United States, did not behave ill to his captors in the camp. The concentration camps with ovens used to commit mass genocide were often not talked about as many soldiers knew nothing of these atrocities and believed “Germany was still the land of beauty and of discipline” [7, pg 5]. While many soldiers stood with the Nazi regime, a few men were strong anti-Nazi and were not hesitant to talk down about Germany and the Regime. The prisoners were a respectful group. During war time, one of the mothers in the town, Mrs. Lameroux, lost her third son in November. The Nazi men stood outside her home with a traditional military salute. Merlin Kraft talked to one of the soliders, Detsel, and asked what was going on. Detsel replied in broken English, “Vee got Mudders too who lost boys 2, 3 maybe? Vee respect everybody who – how you say – make sacrifice” [1, 1996].

Most men could not speak English and, thus, ran their own affairs. Discipline problems were few and far between but when they did arise, the Army would step in and restore the status quo. Following the harvest of 1944, the soldiers moved out of Sparta to the base at Fort Custer. What happened to them after is a mystery. Documents were lost regarding the particular group at the Sparta camp, but some citizens of the community received letters of gratitude from mothers of the soldiers back in Germany for the kind treatment of their sons. Larry Carter finishes the transcription of Merlin Kraft’s lecture with a profound statement regarding World War II and the prisoners kept in Sparta:

Surely there were times when the growers could have been accused of fractionalizing with the enemy. It was a far different country at that time. We were, yet I believe, socially living in what is described as America’s melting pot. There were many familiars who had relatives in both Germany and Italy, whom they had been writing and phoning before the war, “We were only a couple generation away from the sail boats which brought us here. However, we made the same mistake as did the generation before us. We celebrated when the war was over. We thought it had (as did they) been the war to end all wars.” It just doesn’t work out that way, does it? [1, 1996].

World War II was certainly the war to end all wars. It impacted life of those directly in

the war and those at home. While the immediate effects of the war are continually

discussed and learned from, lesser known is their impact on such industries like

agriculture that forced various ag-counties to procure a different type of workforce.

When America undertook the task of becoming an Arsenal of Democracy, industries

that did not immediately impact war efforts were cast aside as it was all-hands-ondeck

to ?ght the enemy at large. While companies like Ford could shift production to

better help wartime efforts, companies like Kraft Farm could not and were not on the

top of the list for keeping their workers. Thus, they employed prisoners of the war to

harvest the fruit that kept the economy of the small town of Sparta grinding away at

their everyday activities. As it turns out, the prisoners were good laborers and some

eventually become friends with their employers. The Arsenal of Democracy is cited in

history textbooks around the United States, but most will not mention the hardships

prisoners of war faced including coming to a foreign land and working for people who

are considered enemies. One for the textbooks would be “America’s Melting Pot: How

the Prisoners of War helped in the United States”. Surely a notion but couldn’t be

more truthful especially for folks like those in Sparta during the 1940s.

Primary Sources

- Kraft, Merlin. “Talk at Sparta Museum, German P.O.W.” 1996, Spartan Historical Museum, Sparta, Michigan.

- “A Message From the Camp”. Sentinel Leader. [Sparta, MI] October, 1944.

- Vining, K.K. “War Labor Camp Benefit to Farmers”. Sentinel Leader. [Sparta, MI] 26 October, 1944.

- “Sparta Prison Camp to Close”. Sentinel Leader. [Sparta, MI] 27 October, 1944.

- Kleff, Karl Heinz. Letter to Mr. Kraft. 1946. MS.

Secondary Sources

- Beard, Charles A. “Education Under the Nazis.” Foreign Affairs (pre-1986), vol. 14, no. 000003, 1936., pp. 442 & 444.

- Mencarelli, J. “The Peach Ridge P.O.W.s.” The Grand Rapids Press, pp. 1-6. (1974, September 15).

- Neldon, Ambrosia. “German Prisoners Worked on Southwest Michigan Farms”. McClatchy – Tribune Business News, Washington, 2013.

- Jaehn, Tomas “Unlikely Harvesters: German Prisoners of War as Agricultural Workers in the Northwest.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, vol. 50, no. 3, 2000, pp. 46–57.

- Karpinos, Bernard D. Height and Weight of Selective Service Registrants Processed for Military Service During World War II. 1958: Medical Statistics Division, Office of the Surgeon General, Department of the Army, 1958. 1.

- “15,870 Axis of War Prisoners in Mid-West Area”. Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963), Chicago, Ill., 1944.

For Further Reading

- Kevin T Hall. “The Befriended Enemy: German Prisoners of War in Michigan”. Michigan Historical Review, 41(1), 57-79. (2015).