In 1959, the U.S. Army contracted with Honeywell Inc., located in Arden Hills, Minnesota, to make classified anti-personnel grenades and mines. Due to the ammunitions being classified material, disposal of the material waste had to have high security. This, combined with being cost effective, led the Army to discreetly dispose waste into Lake Superior. Waste and out-of-specification munitions were disposed only 2 to 5 miles off of the shore of Duluth Harbor, Minnesota for three years.

Many events led the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to dump barrels of munition waste in Lake Superior during the years 1959-1962. There have been many concerns of water pollution after these barrels were discovered. Throughout the late 1900s, many organizations combined efforts to ensure a safe environment for people living in Duluth Minnesota.

The U.S. Army from 1953-1962

After the Korean War ended in 1953, the Army did not demobilize as rapidly as it had after previous wars because of the continuing Cold War. However, personnel strength steadily dropped by 740,000 by 1959 [5, p. 10]. Along with personnel, there was a decline in material resources in response to President Eisenhower’s “New Look” for the U.S. military. Eisenhower declared that the New Look would not allow Communists to deplete U.S. military resources around the world because his new strategy involved nuclear “massive retaliation” [5, p. 21]. Nuclear annihilation would supposedly deter any Soviet threats and provide security at low costs.

The New Look focused U.S. attention and money on the Air Force and Navy because aircraft would carry any atomic weapon used to threaten the Soviet Union. In response, “the public supported the New Look as well as the postwar demobilization and associated defense cuts that fell disproportionately on the Army” [5, p. 21]. This decline in Army resources happened between the years 1953 and 1960, exactly the same time period as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers secretly disposed of munition waste into Lake Superior.

Before concluding that drums should be disposed into Lake Superior, “three disposal methods of the classified wastes were tried” [13, p. 1]. Among these methods, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers researched smelting furnaces, demolition, and pulverization with a hammermill. While there were a few different options in 1959 for munition disposal, the Army found those costs too expensive. Munition disposal was expensive for the Army at this time because “by 1958, the Army received only 22 percent of all defense dollars . . . which was money the Army spent on personnel, equipment, research and development, and any other organization expenses” [5, p. 11]. Limited amounts of funding for weapons and military resources caused U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to choose Lake Superior as a disposal method.

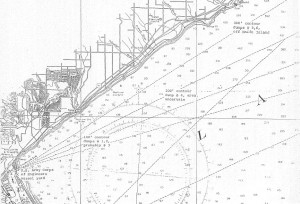

The anti-personnel grenades and mines were manufactured in the Twin Cities Army Ammunition Plant (TCAAP) then driven to Duluth Harbor in 55 gallon drums between 1959 and 1962. The drums were dumped off of Engineer Corps barges in various locations along the shore. Shortly after the Vietnam War ended, The Associated Press released a newspaper story on the munition waste disposal near Duluth. Published in Bemidji, Minnesota, The Pioneer recorded “the Army Corps of Engineers said Monday the barrels hold classified, nonradioactive scrap metal, produced during the manufacture of secret weapons used in Vietnam” [3]. Although the “secret weapons” specifications were not released, Honeywell Incorporated was contracted with the U.S. Army to manufacture small ammunition and grenades. The Army did not release information on the barrel contents until after the barrels were discovered, towards the end of the Vietnam War.

Investigations

The first barrel was found near Duluth in 1968 by a commercial fisherman. After hearing about the fisherman’s findings, the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) started investigating records of ships in the area and was able to confirm that the Army had dumped munition waste five years beforehand [13, p. 2]. The Army was addressed and soon pressured by the Minnesota public to retrieve the barrels.

Shortly after the first discovery, the Army confirmed an investigation to retrieve barrels. The first suspected barrel location was investigated using a magnetometer strong enough to retrieve a 700 pound barrel. The 86th Engineer Detachment (Diving) took the U.S. Army Corps’ derrick boat, the “Coleman”, out to search for dump sites in June 1977. Search costs were $4,000 per day, not including Government personnel salaries [14, p. 77]. At this time, supposedly there were not any known dump sites off of the Duluth harbor. Because of this, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers called off its search for barrels after spending $12,000 of the public’s money [14, p.77]. Bob Dempsey, manager of the recovery project for the Army Corps of Engineers reported that their search was considered a success even though no barrels were brought to shore. According to Dempsey, they found and photographed more than one barrel during the initial searches [4, p. 282]. While the actual dump sites were not found at that time, locating barrels provided a good starting point.

The following years consisted of more investigations from various groups. Some investigations failed while others successfully retrieved more barrels. The public feared that the barrel materials would affect drinking water drawn from Lake Superior, which had intake feeds only a couple miles from the first located barrel. Water samples were taken from known locations to ease public concern, but no chemical leaks or radiation were detected. While approximately ten drums were found and analyzed, it is estimated that the Army disposed 1400-1500 drums during 1959-1962 [1]. Assisted by the EPA Air and Radiation Laboratory, the Corps of Engineers searched multiple barrels and found no radioactive materials.

After many investigations and funding, the MPCA, Engineer Corps, and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) decided to end official barrel retrieval in 1994. The MPCA concluded that barrels did not “present a threat to human health or the environment” [13, p. 4]. While there have been multiple tests confirming there were no chemical leaks from the barrels, many people in the community remained concerned. “Any large-scale environmental cleanup is an expensive proposition, but an underwater cleanup of potentially hazardous materials and explosives is a daunting task” [8]. The public has debated why investigations have ceased before a larger amount of barrels could be found. Many blamed the cost of investigations, and other sources denied the Army’s concern for the environment.

U.S. Army Environmental Awareness

The military’s awareness on environmental pollution increased drastically from the beginning of the 1960’s. By 1965, there were not any recorded occurrences of munition disposal in Lake Superior. Although the production of the munitions was classified information at the time of the disposals, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers later released information regarding the contents of the classified barrels. This shift in environmental protection can also be seen in the U.S. Army Environmental Command’s management of the Defense Environmental Restoration Program (DERP).

Congress established this environmental protection program in 1986. DERP had the responsibility of cleaning any Department of Defense (DoD) sites under the jurisdiction of the Secretary of Defense [10]. There were two subset restoration programs of DERP created, including the Installation Restoration Program (IRP) and the Military Munitions Response Program (MMRP). The barrels from the U.S. Army Core of Engineers and Honeywell contract fell in this category because the Army Core of Engineers discarded military munitions, specifically classified grenades, near Duluth Harbor. Joan Guilfoyle from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Public Affairs Office in St. Paul commented in the Lake Superior Newsletter, published in 1991. She stated that “‘the ecological and environmental awareness of the whole country has changed since the 1960s . . . the Department of the Army is trying to go back and clean things up’” [11]. In this statement Joan refers directly to DERP and the reentrance of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the Duluth barrel investigations at the beginning of the 1990s.

The Duluth barrel investigations were one of many DERP sites the Army had to restore. The Army was required to “investigate and clean up hazardous substances, pollutants, and contaminants at active/operating Army installations, address lands suspected or known to contain unexploded ordnance (UXO) or other munition contamination” [10]. While there were many areas that had to be investigated, the DoD policy stated that certain DERP sites had to be identified and evaluated, and the Army had to restore contamination that they thought appropriate [6]. After analyzing the military waste found in Lake Superior for radiation or other hazardous pollutants, the EPA, U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), and U.S. Corps of Engineers did not find any imminent threats to the public drinking water [14, p. 17]. The Army followed the DoD policy until many reliable sources confirmed no public threat from barrels at the bottom of Lake Superior.

Another indication of the military’s improvement in ecological preservation is the cleanup site surrounding TCAAP. This plant was involved in Honeywell Incorporation’s production of munitions for the Army Corps of Engineers between 1959 and 1962. Waste that was disposed at this site between 1941 and 1981 included volatile organic compounds, metals, explosives, and lead. Because the waste started to contaminate regional groundwater, the U.S. Army began its cleanup by the end of the 1900s [9].

Accordingly, the media repetitively blamed the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers of abandoning their search due to investigation cost. Previous investigations have costed millions, and more funding would be required to retrieve any more barrels. Rumors spread through Duluth newspapers and magazines about drinking water pollution and radioactive exposure, but the Army and many other organizations proved that the barrels posed no threat. The Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) provides recommendations for any future investigations, but there are no intentions of retrieving more barrels. Currently the Mississippi Valley Division of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is responsible for water resource programs in Minnesota.

Between 1959 and 1962 the U.S. Army had a lack of resources which led them to dispose munition waste in Lake Superior. Although these barrels posed a possible public health and environmental threat at the time, an important recovery procedure was formed in response. The Defense Environmental Restoration Program (DERP) holds the military accountable for previous environmental damage and sets the standard for future U.S. Army cleanup procedures. DERP shows that the Army is not only concerned about the people but environmental conservation throughout the United States.

Primary Sources

- Pegors, John (1985). “Preliminary Assessment for Site Number 980679344” St. Louis County Historical. pp. 1-14.

- Sorcusen, P.D. (1962). Daily Report of Operations. Duluth Superior, Lake Superior. N.p.

- The Associated Press. “Officials try to find out what was dumped in Lake Superior” The Pioneer. 2 November, 1976. N.p.

- Oakes, Larry. (N.d.) Recovery project met main goal, feds say. Minneapolis Star Tribune. pp. 1-297.

Secondary Sources

- Carter, Donald A. The U.S. Army Before Vietnam 1953-1965. Center of Military History, 2015. pp. 3-56. Washington, D.C.

- Department of Defense (2012). “Defense Environmental Restoration Program Management.” Department of Defense Manual. pp. 1-95.

- Duluth News Tribune (2013). “A short history of the barrels of military waste in Lake Superior.” Duluth News Tribune. N.p.

- Elko, Tom (2008). “Deep Secret: Military waste remains a Lake Superior mystery.” Twin Cities Daily Planet. N.p.

- Environmental Protection Agency (2016). “Region 5 Cleanup Sites: Twin Cities Ammunition Plant.“ Environmental Protection Agency. N.p.

- Environmental Protection Agency (2012). “Catalog of Environmental Programs 2012.” Environmental Protection Agency. N.P. Washington, D.C.

- Marshall, James R. “Roll Out the Barrels” Lake Superior Newsletter. November-January 1991. N.p.

- Minnesota Department of Health (2008). “Health Consultation: Barrels Disposed in Lake Superior by U.S. Army.” Minnesota Department of Health. Atlanta, Georgia. N.p.

- MPCA (2008). “Facts about the Lake Superior Barrels.” Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. pp. 1-4. St. Paul, Minnesota.

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (1991). Report of Findings: Lake Superior Classified Barrel Disposal Site. St. Paul District, MN. pp. 1-297.