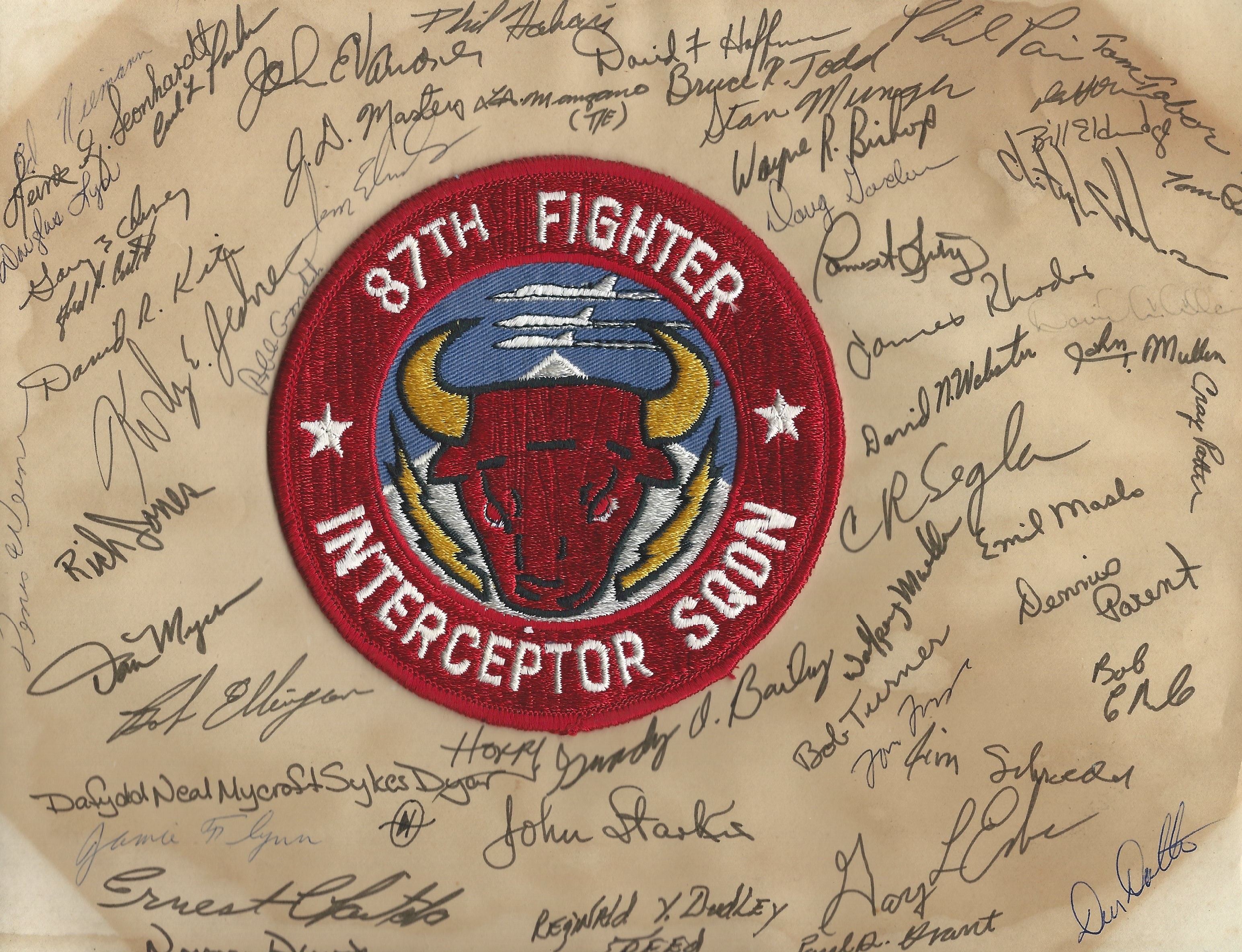

The 87th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, known by their squadron paint as the “Red Bulls” flew F-106 Delta Darts from their base at KI Sawyer to intercept Soviet ‘Bear’ bombers during the Cold War. Although these bombers never approached the key urban centers that they threatened, the role of fighter interceptors and squadrons in air defense against the Soviet threat was crucial. The ability of advanced early warning systems to detect Soviet bombers and scramble fighters effectively prevented any Soviet attacks on American soil. The Soviet bombers seemed to test American reaction times above all else and the Americans were well prepared to react. Pilots and crews honed their skills through aerial competitions such as the William Tell Air-To-Air Weapons Meet. These competitions produced combat-ready pilots and kept squadrons performing at the best of their ability while promoting squadron pride and rivalry.

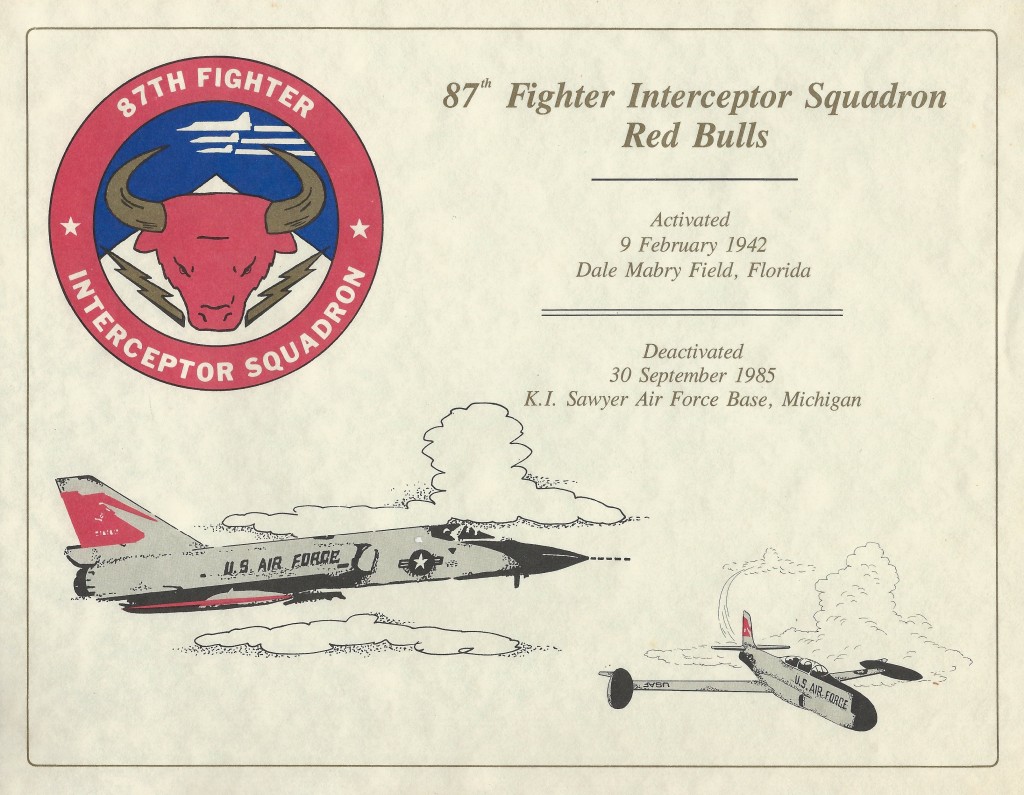

The Squadron

Upon first inspection, it may not seem like a logical decision to place a fighter interceptor squadron in the middle of the Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. However, the realities of the Cold War begged to differ. Not only did the USSR have nuclear weapons, but it also had the aircraft necessary to deploy them. The range of the Soviet TU-95 ‘Bear’ bombers allowed them to attack the United States through the shortest route by flying over the North Pole and Canada, leaving mainland cities such as Chicago, Detroit, and Minneapolis as vulnerable targets [1]. To counter this threat, the Air Defense Command (ADC) established fighter interceptor bases across the nation’s northern border, one of which became home to the 87th Fighter Interceptor Squadron.

In May 1971, the 87th moved from their previous home in Duluth, Minnesota to KI Sawyer AFB in Marquette, Michigan. The 87th had been flying F-106A Delta Darts since 1968 when they replaced the F-101s equipped by the 62nd Fighter Interceptor Squadron which had previously occupied KI Sawyer [12]. Prior to their move, they had already earned a reputation as the “Flyingest F-106 Squadron in ADC” due to their pilots logging an average of 35 flight hours per month [10]. The squadron’s mission at KI Sawyer was to maintain all-weather readiness in interceptor tactics, aerial refueling, and aerial combat. Despite advances in early warning technology, squadrons such as the 87th did not have the luxury of time to respond to a threat. One of the squadron’s essential functions was its ability to be ready at a moment’s notice. At any given time, the 87th maintained two interceptors fully fueled and loaded with weapons, in addition to pilots who slept mere feet from their planes with their parachutes already in the aircraft and their helmets on the seat, ready to be in the air within 5 minutes. In addition, tanker aircraft were scrambled shortly after takeoff to provide the F-106s with fuel along their flight [1]. The F-106 complemented the squadron’s role in every way, and as a pure fighter interceptor, it provided them with the necessary tools to effectively carry out their mission of keeping the Soviets at bay for 15 years. The threat of a Soviet attack necessitated more than just fighter bases, it also necessitated an entire networked command capable of perceiving and tracking Soviet bomber activity north of the United States.

The Threat

In the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, the threat of nuclear war with the Soviet Union was of paramount concern to policy makers around the globe due to the rapid technological progress of nuclear weapons. The first deployment of nuclear weapons in 1945 and subsequent development of Soviet atomic weapons in 1949 clearly illustrated to the world that a new era of warfare had arrived, one in which the enemy could strike swiftly and from great distances to inflict catastrophic damage on military, industrial, political, or civilian targets. At the heart of the Soviet’s nuclear striking capability was a fleet of long range bombers. The ‘Bear’ bomber, in particular, had a 9320-mile range and was capable of striking deep into the American homeland. The U.S. countered the grave threat of Soviet strategic bombers with its own set of early warning systems and fighter interceptor squadrons.

A robust, accurate, and timely system of information was key to the success of fighter interceptor squadrons. The SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment) air defense system was put into practice by the ADC to provide continual target information to interceptor bases across the country when Soviet bombers were detected by a network of long-range radars. The SAGE system used hundreds of radars, twenty-four direction centers, and three combat centers throughout the U.S. to coordinate air defense. The DEW (Distant Early Warning) line of radars stationed throughout northern Canada was one such line of defense, providing critical target information to the direction centers. Using dual state-of-the-art AN/FSQ-1 computers, these direction centers were able to process data from multiple radar sources, utilizing the largest computer programs ever written at the time, which contained half a million lines of code. The North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) was a joint partnership with Canada for defense against the Soviet threat and resulted in both the DEW line of radars and the lesser known Pinetree line of radars, which crossed northern and mid-Canada to detect and track Soviet bombers [9]. Interceptor squadrons such as the 87th were placed strategically to quickly meet the Soviet bombers over the North Pole or Canada and deter or destroy them using aircraft created for that very purpose.

The Plane

The F-106 Delta Dart was the ultimate fulfillment of the 1948 demand for a fighter-interceptor aircraft. The F-106 was a high-altitude interceptor by design, and it met and exceeded its mission requirements in every way, thanks to its ability to travel at a record-breaking Mach 2.31 and deploy both radar-based and infrared-based missiles, in addition to the AIR-2 Genie rocket [11]. The Genie contained a 1.5 kt nuclear warhead. Given the blast radius of such an explosion, the F-106 could fire the Genie from 5 miles away and lead the target based on radar information, allowing the pilot to carefully line up their shot. Once it had been fired, the F-106 was one of the few planes with the maneuverability to make a U-turn and escape the atomic blast. The Genie could take out an entire formation of bombers if it was ever needed [1]. Fortunately, it was not.

The F-106 was a reliable aircraft, capable of withstanding the unforgiving weather conditions of the U.P. and still being available to fly at a moment’s notice. Incidents did occur, however, forcing pilots to react quickly and precisely. In one particular case, two pilots of the 87th were flying a two-seater F-106B used for training, when they experienced oil pressure problems and severe engine vibration. Fearing an explosion, the pilots were quick to shut off the engine and glide their F-106 for sixteen miles back to KI Sawyer, where they managed to successfully land the aircraft with just 10 feet to spare before the runway barrier. The plane’s pilot, Captain Tommy Casey told a local newspaper,

“As it happened, we had the proper combination of elements required for a successful flameout landing: good weather, close proximity to the base, an engine that held on just long enough, a good pilot in the back seat, and maybe just maybe a smidgin of luck” [4].

The F-106’s unique aerodynamic characteristics gave it an edge against other fighters, since its delta wing and internal weapons bay eliminated excess drag, allowing it to maneuver much more tightly than its opponents at higher altitudes. Rather than a conventional elevator or tail wing, the F-106 opted for the use of elevons, which combined the input for the ailerons and elevators into one control surface [8].

An interesting story derived from the F-106’s unique characteristics was the “Cornfield Bomber” incident, in which an F-106 of the 71st FIS went into a flat spin while practicing air combat maneuvers. A flat spin is a deadly condition where the aircraft begins to spin tightly while maintaining a horizontal attitude. In accordance with procedures, the pilot ejected from his aircraft to escape what seemed like a certain fate. Much to everyone’s surprise, upon ejection, the plane leveled out on its own and continued flying until it later landed in a field, gears up, with minimal damage. Apparently, the sheriff arrived at the scene to find the plane in the field, still running, and requested help to shut it down. It is theorized that the proper trim of the aircraft to a neutral position prior to ejection, in combination with the force of the ejection seat rocket blast, was able to return the aircraft’s attitude to normal flight, where it was followed by the other F-106s in the air until it made its landing in a field [2].

Apart from its airframe, the avionics system of the F-106 was a state-of-the-art system unlike anything else. The Hughes MA-1 computer was the first digital computer to be built into a fire control system. As such, it was not necessarily perfect in its first iteration. Over the 25-year lifespan of the F-106, the MA-1 would receive more than 60 modifications and upgrades to remain up-to-date with technological advances. The MA-1 was a 2520lb behemoth consisting of an array of nearly 200 smaller boxes and systems which slid into trays in the F-106’s nose allowing it to pack many innovations into its cockpit [1]. One of these innovations was the Tactical Situation Display (TSD). The TSD was a round, foot wide reverse projection screen located between the pilot’s feet, capable of displaying maps and providing a dead-reckoning mode of navigation, as well as target locations when on the attack. Furthermore, the avionics system allowed the pilot to fly all-weather interceptions to targets using a Heads Up Display (HUD) through the radar scope. The HUD displayed target altitude, heading, range, speed, and force strength, presenting the pilot with all of the information needed to intercept and engage targets [8].

The F-106 could also be flown remotely to a target from SAGE centers, which could place the 106s on an intercept path to any hostile bombers, leaving the pilot to only arm and squeeze the trigger if necessary. The MA-1 onboard computer linked the F-106s to SAGE and allowed for its remote capabilities. This combination of technologies effectively showcased the importance of having interceptors stationed at places such as KI Sawyer to be on alert when the Soviets came knocking [1].

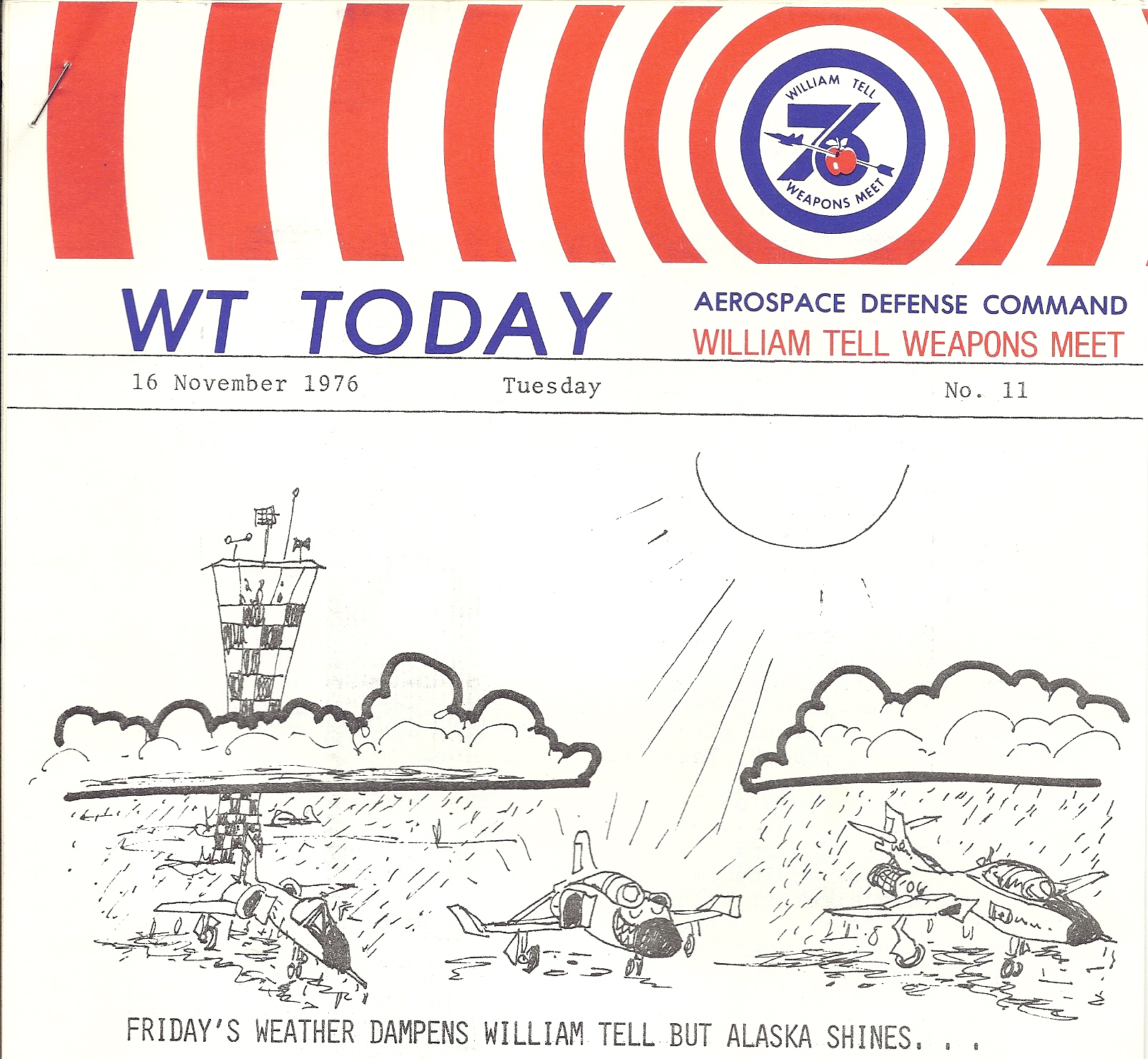

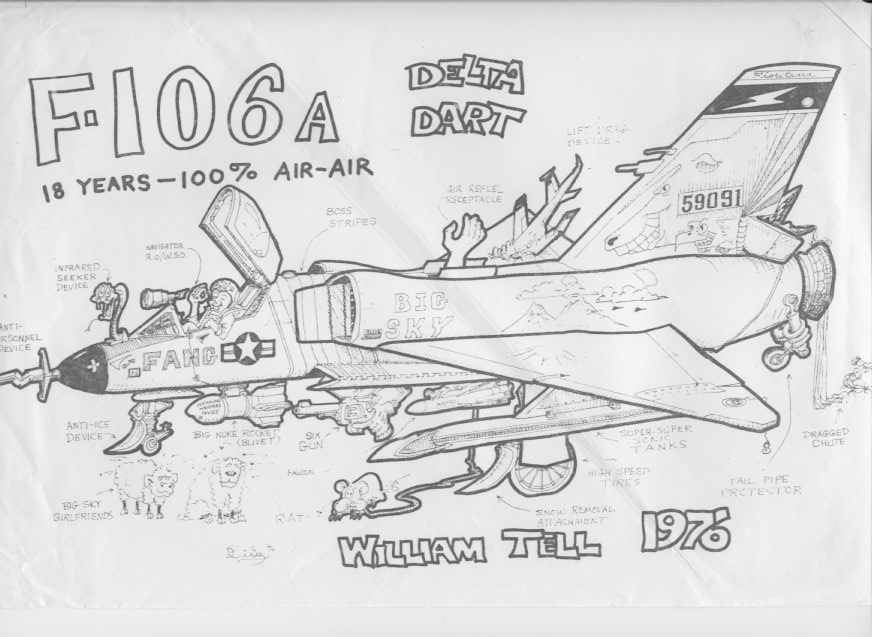

The William Tell Weapons Meet

Interceptor squadrons, such as the 87th, would hone their aerial combat skills further through the Air Force’s biannual Air-To-Air Weapons Meet, referred to as the William Tell competition. The 87th flew their F-106s in the 1972, 1976, 1980, and 1984 competitions. Although they did not earn the coveted awards for Top Gun, or Top Unit during these competitions, they proudly sent pilots and maintenance crews to compete and hone their readiness capabilities [6]. The William Tell aerial gunnery competition has its roots in the 1954 air-to-air rocketry competition. Over the years, the William Tell competition moved to several bases, including Tyndall AFB in 1958, which became the competition’s permanent home. William Tell was about ensuring that the men and machines necessary for air defense were ready. In William Tell ’65, Canadian Forces practiced and competed with the forces of the ADC in a joint NORAD effort.

The competition itself involved sending fighter interceptors against drone targets and destroying them with live munitions. The drones used include the Ryan BQM-34A Firebee, which was a much smaller target than a Soviet bomber. The Firebee used flare pods on its wingtips to maximize its infrared signature, as well as onboard equipment which allowed it to enhance its radar signature and give it the appearance of a much larger target, approximately the size of a Soviet bomber, for the competing aircraft’s weapons system [1].

The Air Force’s 1965 William Tell film repeatedly illustrated that the competition was not merely about piloting skill, although it was a factor. Crew chiefs, maintenance crews, support staff, and radar operators attended as well. The competition emphasized the ADC’s need for interceptors to be ready to go at a moment’s notice. As such, pilots and crew did not know the exact time that they would be chosen to fly, but rather they were given an intentionally vague window. It was up to SAGE radar operators to detect a target drone on their scanners and notify the pilots to scramble to their planes. Time was a critical factor in the competition’s scoring, and proficiency in speed and weapon loading greatly impacted the squadron’s scores. The competition’s winners were awarded a coveted trophy for their squadron to showcase their achievement [3].

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h_GiA3ktnEU

59-0091 “The City of Marquette”

As a result of such friendly competitions, pilots and crew would often add nose art to their planes to show off their squadron pride. Many such squadron-themed nose art paintings were done by Dick Schultz, a career fighter pilot and fantastic cartoonist responsible for the colorful nose art of many of the 87th’s F-106s, including ‘Big Red 1’, ‘Lurch IV’, ‘Bones Crusher’, and ‘The City of Marquette’, named after the city near the 87th’s home base at KI Sawyer. Schultz flew ‘The City of Marquette’ in the 1972 William Tell competition [7].

Unfortunately, the colorful decorations of the 87th did not last. At some point after one of their William Tell competitions, the nose art had to be painted over. Despite this, the nose-art was still visible, hidden beneath the light coat of paint, and the likes of ‘The City of Marquette’ and ‘Lurch IV’ could still be seen by the proud personnel of the squadron, and those who took a close enough look. The true death blow to the nose art of the squadron came later when modifications had to be made to the F-106s. The Genie nuclear rocket was being phased out and instead, a minigun was to be added so that the F-106 could adapt to the changing times and be a more adept dogfighter. During the modification process, the planes were thoroughly repainted once more, this time with paint designed to reduce the aircraft’s drag, enabling marginally higher speeds, in addition to being a grey-blue tone designed to better blend in with the sky [1].

Dick Schultz’s F-106 ‘The City of Marquette’, S/N:59-0091, would ultimately end up in a similar fate to many F-106s, being sent to Davis Monthan AFB for storage in May 1983, being converted into a QF-106 drone in 1992, and being shot down in 1994 by an AIM-7M as target practice. The military cited the “age and limited usefulness of the F-106 fighters” as the reasons for pulling it from active duty [5]. The end of the F-106 was not due to an inability to fulfill its mission; to the contrary, it is quite the opposite. The Air Defense Command’s fighter interceptor program was an extremely successful deterrent against the Soviets. In the competition of superpowers, probing and testing each other, the interceptors functioned as intended. The Soviets were decidedly less interested in actually attacking the U.S. then making a show of force and testing the American’s reaction times. The ADC’s 5-minute alerts proved to the Soviets that if they were ever to try anything, the ADC would be there with interceptors capable of stopping them. Amazingly, F-106s were not the last planes to intercept Bear bombers, and F-15s, F-16s, and even F-22s have intercepted Bear bombers to this day, proving the vigilance of our aerial defenses.

When the 87th FIS finally left KI Sawyer on October 1, 1985, it was a sad day for the squadron’s personnel [5]. The increasing range, accuracy, and availability of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles, ICBMs, meant that the strategic necessity for a dedicated interceptor aircraft was obsolete before the actual hardware was. While the F-106 could do a great many things, it was not meant to intercept an ICBM. The F-106 had ultimately done its job so well that it no longer had a target to engage [8].

Primary Sources

- Roznick, John. “Overview of Time with the 87th.” Personal interview. 16 Oct. 2016.

- Foust, Gary. “VN520669 Gary Foust On 787.WMA.” Interview. F-106 Delta Dart. SoundCloud, 2014.

- William Tell 1965. Prod. 1365 Photo SQ. Aerospace Audio – Visual Service, 1965. Film.

- “Pilots Glide Damaged Dart to Safe Landing.” The Northern Light [Gwinn, Michigan] 25 Oct. 1973, 6th ed., sec. 38: n. pag.

- Silfven, Ken. “87th FIS Era Ends at Sawyer.” The Northern Light [Gwinn, Michigan] Sept. 1985: n. pag.

- “Sawyer Competition.” The Northern Light [Gwinn, Michigan] 1976: n. pag.

Secondary Sources

- Carson, D. A., and Lou Drendel. F-106 Delta Dart in Action. Vol. 15. Warren: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1974.

- Deal, Duane W. “F-106 – Biggest Deal Of The Century Series.” Wings June 1984: 20-29.

- A Brief History of NORAD. By Charles H. Jacoby. North American Aerospace Defense Command. North American Aerospace Defense Command, 31 Dec. 2013.

- “87th Flying Training Squadron.” Laughlin Air Force Base. Laughlin Air Force Base, 1 Dec. 2008.

- “Convair F-106A “Delta Dart”” K.I. Sawyer Heritage Air Museum. K.I. Sawyer Heritage Air Museum, 2015. Web. 16 Oct. 2016.

- “87th Fighter Interceptor Squadron.” F-106 Delta Dart. F-106 Delta Dart, 2016.

Further Reading

- “The SAGE Air Defense System.” MIT Lincoln Laboratory: History. MIT Lincoln Laboratory, 2016.

- “The Hughes “MA-1” System.” THE 456th FIGHTER INTERCEPTOR SQUADRON. 456FIS.ORG, 10 Feb. 2014.

- “Aerospace Defense Command.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d.

- “87th FLYING TRAINING SQUADRON.” USAF Unit History. USAF Unit History, 28 Oct. 2010. Web. 17 Nov. 2016.