During the Cold War, development of the atomic bombs took place in the deserts of the southwestern United States. These areas provided vast, unpopulated areas to safely test weapons of mass destruction, but they didn’t represent the climate of the Soviet Union. In north-central Minnesota, large peat bogs provided a location for the military to train and test ordnance. The cold Minnesota winters presented the perfect conditions to test bombs that could be used against the Soviet Union. During the winter of 1951, the military had an implosion-type nuclear bomb that they wanted to be sure would detonate 3000 feet in the air in the middle of a frigid winter. To test this they removed the nuclear core from a bomb, and dropped it above Upper Red Lake. As the bomb floated toward the ground beneath a parachute, the barometric (atmospheric pressure sensing) fuse read the altitude. At 3000 feet above the ground, the fuse detonated the bomb, and thousands of pounds of conventional explosives created one of the largest fireworks northern Minnesota has ever seen.

Cold War Development

After World War II the Atomic Energy Commission was created to regulate and control nuclear material and research. Even though it was a civilian agency, not a military one, it was also tasked to continue development of nuclear weapons. The Atomic Energy Commission worked closely with the newly formed Strategic Air Command of the U.S. Air Force to ensure that safe methods could be developed to transport, drop, and detonate nuclear bombs which were rapidly increasing in strength with technological development.

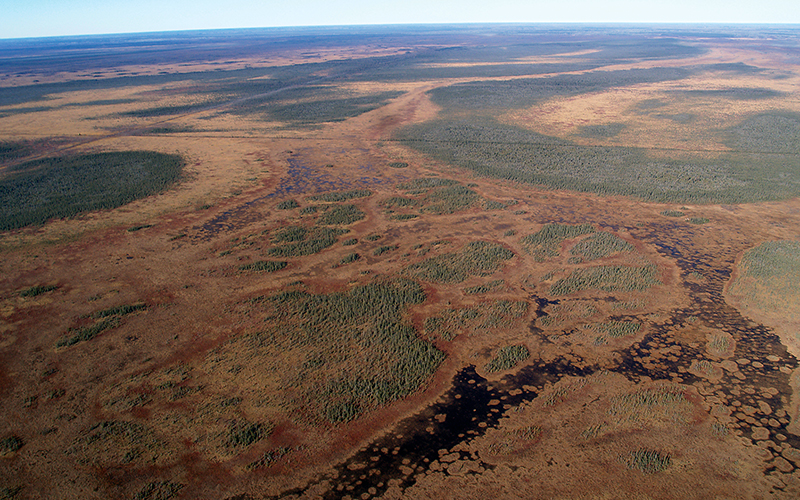

In the opening phases of World War III, it was expected that Soviet bombers would fly over the North Pole and Canada to strike at the Midwest. To defend against attacks from the north, a vast radar net was placed across the top of Canada, providing early warning of incoming bombers and missiles. Should an attack be detected, fighters and anti-aircraft guns based along the northern edge of the United States would prepare to save the U.S. homeland. Minnesota and the Dakotas housed military bases for these troops, but keeping the troops in fighting condition meant that they needed a location to practice. The expansive Red Lake peatlands north of Upper Red Lake were selected as an artillery and bomb range. Aircraft from Duluth, the Twin Cities Naval Station, the Dakotas, and troops from Camp Ripley trained, tested, and shelled the bog incessantly during the late 1940s and early 1950s [9]. Many of these bombs were simply for targeting practice and were filled with water rather that explosives, but there were cases where live munitions were used. In one such case the Minnesota Department of Conservation requested that live bombs be used to destroy areas of peat, opening up ponds for moose to wade [8].

While the Peatlands were a relatively small range, not capable of safely testing large live bombs and artillery shells, their location in northern Minnesota became their most important contribution to the Cold War. Previous bomb tests had taken place in Nevada, New Mexico, and in the southern Pacific at Bikini Atoll. These locations poorly simulated the climate of the Soviet Union. Although the peatlands were too small to safely test a live atomic bomb, they could handle simply testing the bomb’s fuse. This was still no small explosion by conventional standards, but the ability of the northern Minnesota winter to simulate the Soviet Union was too enticing for the scientists and engineers developing the atomic bomb.

To create a nuclear reaction, fissile nuclear material must reach a critical mass. One way to achieve this was to fire two chunks of material at each other in what is known as a gun-type device. The two pieces mesh together, forming a mass of fissile material large enough to create a chain reaction. Another method is to surround a chunk of fissile material by conventional explosives and simply crush the material with a massive explosion. The fissile material instantly increases in density due to the explosion on all sides of it and immediately erupts in a nuclear explosion. This is known as an implosion-type device. The fuse tested over Upper Red Lake belonged to an implosion-type bomb. This meant that even without the nuclear material, the bomb contained thousands of pounds of conventional explosives. Fat Man, the bomb dropped on Nagasaki at the end of World War II, contained about fourteen pounds of plutonium and weighed over ten thousand pounds total. Although there are other systems within the bomb besides conventional explosives and the plutonium core, the explosives are a significant portion of the weight.

Due to the immense power of atomic bombs, they are very difficult to deliver. If the airplane were to simply drop them like a conventional bomb, they will fall to the ground and detonate long before the plane has left the area. To save the airplane and the crew, atomic bombs were fitted with parachutes so they would slowly fall towards the ground giving the airplane time to get away. Furthermore, atomic bombs do the most damage when they detonate above the ground because the blast can travel more easily across a wider area. For both of these reasons, the bombs of the day used the altitude sensor to determine when to detonate. The altitude fuses read the barometric pressure and exploded when they reached the proper height above the ground. Atmospheric pressure can be affected by the climate so it was necessary to ensure the bombs would work not only in the desert, but also in the frigid winters of the Soviet Union.

The Megaton Blasters

Due to the highly dangerous and highly classified nature of the atomic bomb development, the Strategic Air Command designated a single U.S. Air Force Wing to test them. This was the 4901st Support Wing, and under them, the 4925th Test Group, known as the Megaton Blasters [6]. The 4901st was responsible for ensuring that the bombers of the day could carry, release, and target nuclear weapons effectively. It was also responsible for monitoring nuclear fallout and through the 4925th, dropping the live weapons for tests [7]. The 4925th was based at Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico, but was responsible for all air-dropped nuclear weapons testing including the ranges in the Pacific Ocean and Nevada. This group was formed from the most elite pilots, navigators, bombardiers, and radar specialists in the U.S. Air Force. The Air Force decided that every new bomber built should be capable of carrying nuclear weapons so the 4925th tested bomb carrying and targeting with the F-89J Scorpion, B-45 Tornado, B-47 Stratojet, B-36H Peacemaker, B-29 Superfortress, B-50D Superfortress, B-57 Canberra, and B-66 Destroyer airplanes, among others. In 1956, the atmospheric testing portion of the 4901st was handed over to the 4950th wing as their sole task. In 1961, both the 4950th and the 4925th were deactivated and their tasks were handed off to other units.

Northern Minnesota Winters

By the winter of 1951, the residents of the peatlands area had grown accustomed to the drone of airplanes and the explosions of artillery shells. This is not to say that they were always happy about it. The Red Lake Reservation encompasses all of Lower Red Lake, most of Upper Red Lake, and many additional areas throughout the Peatlands and further north. During the peak of the Cold War, the leaders of the Red Lake Ojibwe Tribe authorized the U.S. Air Force to use their reservation for bomb testing, but after many years of incessant explosions, the Ojibwe had grown tired of it. The reservation finally closed for bomb testing in 1965, and in 1978 stated that no military aircraft were even allowed to fly over it with one Ojibwe leader threatening to shoot at any military flyovers he happened to see [1].

Even for those who were used to it, the bomb testing could be terrifying. During the early months of 1953 the Civil Defense Director of International Falls, Minnesota said that B-36 Peacemaker bombers dropped three separate atomic bombs with the nuclear material removed and detonated them four thousand feet above Upper Red Lake [2]. These drops were denied by the Atomic Energy Commission but Anna Gibbs of the Red Lake Ojibwe witnessed many bombings as a nine year old girl living along the lakeshore [10]. Although she doesn’t state whether they were nuclear tests, she recalls one night in particular where the bombs shook her house enough to knock pictures off the wall, smashing the glass when they fell to the floor. She was terrified and ran out the door as the airplanes came in for a second pass. She watched trees fall across the lake and heard the ice crack as the explosion shockwaves echoed back and forth across the lake. Her family’s ponies were also panicked so she took her favorite one and quickly rode to one of her favorite places among the sugar maple trees, six miles away from the bombs.

The explosions from standard five-hundred to two-thousand pound bombs was enough to shake the houses and terrify those who lived right along the lake, but there were a few explosions that were clearly not normal bombs. At about 8:30pm on the evening of Monday, December 15, 1952, residents of International Falls stated that they heard what sounded like an explosion [3]. Many initially assumed it was a meteorite or an earth tremor while some assumed that a gas tank had exploded and others stated that their windows rattled from the sound of a large crash. Furthermore, some teenagers stated that they had seen a bright light in the sky to the west. The Red Lake Bombing Range is about sixty-five miles west-southwest of International Falls so these stories point to the fact that a bomb of greater than average yield was tested that evening.

Not allowing the area residents any rest, around midnight before Wednesday, December 17, 1952, many again reported loud noises. This time it seemed to be more of a rumble. International Falls residents reported hearing noises such as a door knocker, a rattling, and a banging. Some area residents even stated that they had heard the rumbling noise and seen flashes on the horizon every night from Saturday, December 13 until Wednesday the 17. The next day, an Air Force Major stated that the Air Force had been conducting cold weather explosive tests on the Red Lake Bombing Range [4].

All was peaceful around International Falls for about a month, then reports again flowed in of bright flashes and loud explosions. Residents stated that the explosion of Monday, December 15, 1952 sounded and felt similar to a blast that occurred in February 1953 and also to a blast that occurred at 2:55 am the morning of March 9, 1953 [5]. While only a few people had reported seeing flashes for the first and second of the three similar blasts, many area residents reported seeing the flash early in the morning of March 9.

The Peaceful Bog

During the early 1960s, the peatland was used intermittently for training. By the late 60s, modern artillery weapons were too powerful to test within the confines of the Red Lake Bomb Range and the Red Lake Ojibwe had revoked their authorization for the Air Force to use the land for bombs. In the mid-1970s the Red Lake Peatlands were granted protection as a National Natural Landmark. Currently, a boardwalk runs through portions of the park and some of the ponds created by live bombs have yet to heal over with new peat [11].

Minnesota no longer has a bomb testing range but it is no longer needed. The Air National Guard 148th Fighter Wing based in Duluth, MN has no nearby location to drop live bombs, but their F-16 Falcons can be seen across the Iron Range from time to time dropping flares as they mock-dogfight to stay practiced or flying formations over events.

The military still performs tests and training in cold temperatures. Although they no longer frequent Minnesota, the recent discourse with Russia has prompted the United States military to increase cold weather training. Long range B-52 flights over the North Pole have become more common as the U.S. Military executes Operation Polar Growl and improves strategy, operations, and tactics in a cold environment [12]. The Red Lake peatlands may have been a valuable test range in the past, but the strength of modern weapons and protection by the Minnesota DNR will allow them to heal, knowing that they will likely never be bombed again.

Primary Sources

- Treuer, Anton. Warrior Nation: A History of the Red Lake Ojibwe. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 2015.

- Australian Associated Press. “Atom Bomb Tests In Minnesota.” The Cairns Post, 21 Feb 1953, p. 3

- The Daily Journal. “Did Earthquake or Meteor Shake Border District” The Daily Journal [International Falls, MN], 17 Dec 1952, p. 1

- The Daily Journal. “Mystery of Nocturnal Explosions Is Solved” The Daily Journal [International Falls, MN], 18 Dec 1952, p. 1

- The Daily Journal. “Unexplained Flash, Explosion Awaken Residents Early Today” The Daily Journal [International Falls, MN], 9 Mar 1953, p. 1

- Hardison, John D. The Megaton Blasters. Boomerang Publishers, 1990.

- United States, Defense Nuclear Agency. DNA 6021F: Shots Easy, Fox, George, and How. The Final Tests of the Tumbler-Snapper Series 7 May – 5 June 1952. National Technical Information Service, 1982.

Secondary Sources

- Easthouse, Doug (2010). Bombing the Big Bog.

- Weber, Tom; Lager, William (2016). When the U.S. Military Bombed the Bogs of Minnesota.

- Weber, Tom; Lager, William (2016). Looking Back On the Bombed Bogs of Minnesota.

- Brown, Aaron (2016). Cold War Bombs in The Bogs of Northern MN.

- U.S. Strategic Command Public Affairs (2015). Polar Growl Strengthens Allied Interoperability, Bomber Navigation Skills.

For Further Reading