Shown above is the partially restored Fort Malden, currently the location of the Fort Malden National Historic Site Museum. On the right is the restored estate house, which was built after the Fort’s closing in the late 19th century. On the left is shown the deep-water channel of the Detroit River.

Fort Malden was a British fort built before the War of 1812 to defend and control the Detroit River. More recently known as Fort Amherstburg, the Fort is located close to the southern mouth of the Detroit River. Its strategic location on the river allowed it to completely control access through the river to the Upper Great Lakes, and its tactical location on a narrow stretch of the river allowed it to have very effective firing positions over any ships attempting to pass through. In the War of 1812, the Fort served as a point of contest between American and British Forces, until the Treaty of Ghent ended hostilities in 1815. After the War, the Fort was again used by the military, as a base of operations for quelling the Upper Canadian Rebellion in 1837. After some assorted other uses in the following peacetime, the site has now been designated as a National Historic Site, and now holds a public museum.

The Strategic and Tactical Value of Fort Malden

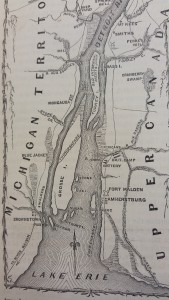

The strategic purpose of the fort throughout its military history had been its location on the Detroit River, the main waterway connecting the Upper and Lower Great Lakes. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the Great lakes had been the main transportation route from moving all types of materials throughout the upper Midwest; from initial fur trading with Native Americans, to the eventual lumber, grain, coal, and ore industries. By controlling this river, the British could maintain effective control of any movements between the two lakes, and therefore could control the trading through the same.

Along with the fort’s strategic location along the Detroit River, the fort was also tactically placed on a narrow, deep channel of the Detroit River that at the time was the only route for deep-hulled ships. According to current NOAA soundings (water depth) documents, the channel is still one of only two routes up the river than have consistent depths greater than four feet [2], the second being dug in 1910 [3]. This meant that before 1910, every significant ship passing through the Detroit River had to pass through the Amherstburg channel, and therefore within just 500 yards of the fort’s guns. Without control of this fort, safe movement up or down the Detroit River would have been extremely difficult in times of war.

Fort Malden in the Outset of War

Fort Malden was the site of the very first ‘battle’ of the War of 1812; so early in the war was this, that the American commanders had not yet received word that the war had begun! On July 2nd, 1812, an American schooner Cuyahoga Packet with American troops and supplies preparing for the likely invasion of Canada was unexpectedly intercepted at Fort Malden, and the troops were captured. Due to the slow communication abilities at the time, the British commander (Gen. Isaac Brock) at Malden had already received word of the US Declaration of War, but the US Commander (Brigadier General William Hull) had not. This is recounted by Surgeon’s Mate James Reynolds who was the deputy of Surgeon General Edwards, who was charged with the sick on the vessel when it was captured. Reynold’s Journal was kept and maintained, and in it he penned the following about the event:

July 1st (1812). (….) To our surprise just as we were about to enter Detroit River we saw a boat that hailed us and ordered the Captain to lower his sails. Our arms were all in the hole (hold) and the men sick. I thought it improper to make any resistance as I had not been informed that war was declared and had not had orders from the Genl. to make any resistance. Lt. Goodwin and 2nd Master Beatt and Mr. Dent paymaster to the 3rd Regt. Ohio Vlts. and three ladies and two soldiers wives making in the whole forty-five in number and not more than six well persons among them it must have been imprudent in the highest degree to have attempted to resisted a boat of eight well-armed men and a Capt., and another of 5 men who demanded us as prisoners of war and we were nearly under the cover of the guns at Ft. Malden, soever we gave ourselves up and was taken into Malden and our property was all stored in the hole (hold) and hatches nailed immediately and we were taken alongside a prison ship. The next morning about X o’clock our Schooner was taken and all our effects even to a blanket. The Doctor came on board to see some of the sick and I asked him for knapsacks and blankets for the men which were returned immediately and the cloths of the officers and men on board. [8]

While still prisoners of war, the captured troops reported still being well treated later in the journal, and were eventually returned to the US after an American counterattack later in the fall. This is a perfect example of how little the British wanted to engage in the War of 1812 as defenders from invaders, as well as how unorganized much of the war was by American forces. As it can be seen throughout the war, the Americans were not very clear in their goals of the invasion, and neither side was ultimately prepared or supplied for a full war effort.

The Detroit Campaign of The War of 1812

In the war of 1812, the fort was a major point of contest in the American invasion of Upper Canada. While the attacks on Niagara and the larger cities further east are more well-known for the War, the ‘Detroit Campaign’ was the first conflict. This began as a fight between General Hull’s American Army and a small patrol of British at Sandwich, which marked the first casualties of the War of 1812[6]. This type of light and irregular fighting continued for the first few months of the War, on both sides of the Detroit River.

The next major attack in the campaign was the surrender of Fort Detroit. As a counter to the American attacks into Canadian territory, the British General Brock led a counterattack with the help of thousands of Tecumseh’s warriors towards Fort Detroit on the US side. On August 15th, 1812 General Hull surrendered Fort Detroit to the British. More information about Fort Detroit is also available here. Overall, the surrender of Fort Detroit (without a fight) was a huge loss in the American effort, and set back the American offensive into Canada by nearly a year.

As the battle over the other campaigns continued at Niagara and Lake Erie, as well as the fight with Napoleon in Europe, the consequences of the British fighting in multiple wars began to take its toll. Whatever small amount of resources the British were able to send to their Canadian territories were dispersed to the strategically prominent Niagara Campaign. This, coupled with the loss of the Battle of Lake Erie, ultimately strangled the ability of the British to continue fighting in the area. Directly after their win in the Battle of Lake Erie, the American forces moved back north and recaptured Fort Detroit after the British evacuated. The remaining British then fell back briefly to Fort Malden, before completely leaving the Detroit River basin altogether in September of 1812. [6]

During the evacuation, to deny the Americans any additional resources, the British torched and destroyed the majority of Fort Malden. In their retreat, the British eventually turned around to fight in the famous Battle of the Thames, where they were defeated and forced to retreat even further away. Perhaps more importantly, this battle also marked the rough end of Native American support of the British on this front, as the Chief Tecumseh was killed in the battle. While they had played a significant part in the attack on Fort Detroit and the defense of Fort Malden, the loss of Tecumseh broke the back of the Native American assertiveness in the war. After the Battle of the Thames, most tribes removed their association with the British. [7]

US Occupation and Rebuilding

Following the torching of the fort, the American forces were able gain control of the remnants of the fort and the nearby Amherstburg. Through 1815, the US rebuilt and occupied the fort as a base of operations for the further invasion into Upper Canada leading to the eventual end of the War of 1812. In late 1814, the US and Great Britain signed the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of 1812 and returning the captured land in Canada to Great Britain. In the summer of 1815, the US troops left the fort and returned it to British forces.

Involvement in the Upper Canadian Rebellion of 1837

After the Treaty of Ghent in 1815, the fort was again revitalized in 1838 to defend against rebels and sympathizers during the Upper Canadian Rebellion. Many of the rebellion’s sympathizers were in the United States, and they mounted multiple attacks against the British at the fort (unsuccessfully). The reason for the rebellion is best described by John Charles Dent in his book “The story of the Upper Canadian Rebellion” published in 1865:

The oligarchs had taken alarm. If this man were permitted to go on as he had begun, there would soon be an end of the existing order of things, which they had so tremendous an interest in preserving. At any cost, and by whatever means, he must be suppressed. There must be a general and determined advance against him all along the line. [10]

The rebellious citizens that wanted to remove the oligarchy government of the Upper Canadian territory (and that were supported by sympathizing Americans) were put down within a year by troops based from Fort Malden.

Recent Peacetime

Once the rebellion was ended, the British mostly withdrew from the fort, and it did not see combat again. In the years after, it saw use as a mental asylum and a lumber yard, and eventually it was sold off to local landowners [11]. In 1921, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board recognized the fort as a National Historic Site, and the fort is now the site of a public museum on the original grounds. The Fort Malden National Historic Site Museum is free and open to the public, and features multiple reenactments and exhibits on the Fort, as well as the War of 1812. [4]

Secondary Sources:

[1] Smithsonian National Museum of National History. On the Water – Inland Waterways, 1820-1940. n.d.

[2] Office of Coast Survey. “14853_07.” n.d. NOAA Chart Catalog. 1 12 2017.

[7] Britannica Academic. Battle of the Thames. n.d. 01 12 2017.

Primary Sources:

[9] Hawk, Balck. Autobiography of MA-KA-TAI-ME-SHE-KIA-KIAK, or Black Hawk. Project Gutenberg, 1832.

[10] Dent, John Charles. The Story of the Upper Canadian Rebelion. C. Blackett Robinson, 1865.

For Further Reading: