The year is 1944, the world is defined by conflict. America is fighting a war in the East and the West, and there’s still a lot more fighting to do. Many defeated soldiers of the Axis Powers were captured and brought to the USA as prisoners. Many of these prisoners of war were German or Italian and many were brought to the northern Midwest region of the United States. Many of the prisoners brought to Itasca County in Minnesota were captured after Rommel’s defeat and the end of Axis forces in North Africa. This research will be about the experiences that German prisoners of war had in internment camps in Northern MN as well as the differences between this system and others.

This would not be the first time Germans would be imprisoned in America. During the WWI era, German prisoners who were captured overseas or arrested in America on charges of espionage or aiding the enemy were put in military work camps. This was not a very large operation, and it went very smoothly. They were kept in good conditions, were paid for their work on roads or as mechanics, and kept lively sports competitions. The suspicion of Germans began before America entered the war, propaganda about German spies started circulating in 1914, and the arrests for these didn’t stop until February 1919, a year after the war ended (Yockelson). This style of operation for labor camps was reused for prisoners in WWII.

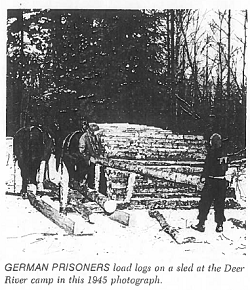

Itasca County Minnesota: known not for much, but home to a large amount of local industry. During the war, the abundance of trees and access to the Mississippi River made the region ideal for logging. After the war, the area became known as part of the Iron Range, for the abundance of iron ore deposits in the region. If these operations were running during the war, there would have been more than a few German miners. One useful feature of keeping prisoners around was that they could perform some of the much-needed labor that the United States needed in the war. German POWs were not sent only to logging camps. Across the country, captives would play a big part on many farms or factories that were far enough from government buildings and not a security risk.

Labor Camps

German labor provided by these camps was integral to winning the war. Without industry on the home front, keeping a war going is hard, keeping a world war going across an ocean is impossible. The civilian effort to transform American into the “arsenal of democracy” was excellent. The sheer output of the American people during the war is likely the biggest factor in America and the Allied Forces turning the war around and finishing it. As the war continued, the labor shortage did too. As more and more able-bodied men volunteered or were drafted to fight, less and less able-bodied men remained on the farms and in the factories. The addition of German prisoners was a vital boon to the USA wartime economy. Near the end of the war, some large farms were so happy with the POW work system, that they were requesting 100,000 more prisoners to be brought back.

Many internment camps had no fences to keep prisoners in. The war had caused a shortage of steel, so German prisoners easily could have walked off into the woods. But did they? No, apart from a few small incidents, very few Germans attempted to escape these camps. It may sound strange that prisoners of war in WWII wouldn’t want to escape, but that is where the internment camps of German soldiers differ from German camps, or even the Japanese internment camps on the West Coast. The Germans liked it there.

The prisoners in these camps were not treated poorly, in fact, the opposite is much more accurate. The story of their non-abuse begins on the boat bringing them to America. On the boat, all prisoners are fed very well. Upon reaching the USA, the prisoners were brought to their camps in nice furnished train cars, again fed well. When they reached their camps, the Germans saw that they would continue being given full meals every day, along with a daily paycheck in camp scrip to buy beer and cigarettes at the camp store. Their living quarters were comparable to a room that a US soldier would be boarded in. All they had to do was an honest day’s work every day. That’s not to say they were treated too comfortably, they had to wear marked clothing while working. The guards would tell stories about the dangers that lie in the woods. Tales of wolves, bears, and hostile natives helped deter attempts of escape (Pluth).

It is true that very few Germans attempted escape, however, some did. Lobdell wrote in Minnesota History the entire story of one such escapee. The prisoner, after being interned for well over a year, was very worried about the European Theater. Having been in the region that long, he had learned that wild animals and wild Indians were not the threat they were made out to be. POWs at the camps were allowed mail communication with their loved ones. After this man had learned from seeing newspapers that the Soviets were closing in through Poland, and that his grandfather was being drafted, he knew he had to act. He, and his friend, would escape the camp and return to the front and fight for Germany. They did not end up saving Germany. They were captured and brought to the Grand Rapids county jail.

Escape

The testimony given by the escapees, Shymalla and Mai, details their adventure. They began stocking up food in the days previously by saving their rations that they would have had in the woods. 28 strips of bacon, 2 pounds of sausage, and a few loaves of bread. Shymalla and Mai brought these rations to a boat in a nearby lake. They had built this boat the previous summer while at the work camp. The fence around the camp was a wire fence that was easily separated to allow for the Germans to make a hole large enough to carry supplies through. Shymalla recounts that he brought an American army field equipment kit that they use during their work, along with a few sets of clothes. They had no weapons, they were just trying to escape. Mai and Schymalla had not planned very far ahead, they admit they had not thought about passports in order to get back to Germany. They weren’t even sure which way they were going to get to Germany. Schymalla argues he would have been able to get down the Mississippi, fight his way into Mexico, and then work until he could afford travel back to Germany. Or maybe he would get to the Bering straight and work his way to Japan, allies with Germany, who would send him home. Lucky for them, they never needed to plan this far ahead.

After sneaking the supplies out to the boat, they went to their beds with their last set of clothes so that they would be accounted for by the guard when he came around at 11:00pm. After the count, they snuck off through the fence and to their boat. During the night they pushed the boat off into the lake and began their progress. They made their way through the lake and by daybreak they had gotten to the lake connected to it. In the light they were surprised by a fisherman in the lake. The fisherman left, and the brave soldiers carried onward.

That night they stopped at the side of the lake to rest. 2 more days of journey in the cold harsh Minnesota winter was draining them of their supplies and spirit. At another lake near Ball Club, east of Grand Rapids, the same fisherman had found them, and shortly called the police. The Grand Rapids Sherriff had arrived with a few men and began to surround the tenacious duo. The law enforcement didn’t do a great job, Shymalla notes that the policemen walked past them once. At that point Schymalla and Mai surrendered and started calling out to them to be found. They were then brought to the Grand Rapids prison, and kept until their transfer back to the military. After their testimony they were sentenced to 30 days of confinement with 14 continuous days of a restricted diet of only bread and water.

Treatment

Those who didn’t join their adventure found themselves very satisfied with life in the camps. Their humane treatment is, in fact, required of the Geneva convention. Prisoners of war are to be given the same food as the guards, and roughly the same housing as the guards. If the prisoners were to be put in tents, so too must the guards live in tents. The convention mandates that the prisoners of war are to be paid a fair wage, but, like stated, they were paid in camp scrip instead of cash. The reasoning behind the scrip was not to make the Germans start singing about owing their soul to the company store. They were not given cash because, if they were to escape, they could use that cash in nearby towns. But, like the opposition to labor, there was opposition to how well the POWs were treated.

There were complaints in the towns near these camps that there was indeed unfair treatment going on. However, not to the prisoners, but exactly the opposite! Many civilians thought it was unfair that these prisoners were given bacon and sausage when there was a war on and meat was a rationed resource. Civilians were pressured to work harder, work overtime, buy war bonds to support the troops, and German prisoners were being given better food and time to relax during the day. Some Americans also complained that their women were being romanced by Germans when they were allowed in the towns.

The most egregious social inequality comes from a modern perspective. When the POWs were allowed in the nearby towns to spend their earnings, they were allowed to enter segregated restaurants when black Americans were not. This was in America before the Civil Rights Movement, and this would be cause for outrage. This was a clear example of enemy prisoners being treated objectively better than American citizens.

Legacy

The Itasca County labor camps were part of a little known event in American history. The average American probably would be shocked to find out we had “forced labor camps” for prisoners of war during WWII. The reason we don’t hear about it, is because it went so smoothly. Despite some social pushback from the surrounding region about dangerous enemies nearby, labor, quality of life, and discrimination, the camps ended up a huge success. The labor provided by these soldiers was a necessary boon for the workforce weakened by the war. While a few prisoners were able to escape a few miles, most prisoners didn’t want to.

After the war, most prisoners went home to their families in Germany, but some made a life in northern Minnesota and their legacy in the local industries and culture still exists today. In some other examples of POW labor camps, the thought of the prisoners wanting to return to the area and speaking highly of the experience is strange. That is what makes the German POW camps in Minnesota during WWII a story worth telling. Not a horror story, like the Holocaust, but a story about honorable soldiers treating their fellow man with respect.

Primary Sources

Colonel Lobdell. “Transcript Of Testimony Taken At Hearing At Prisoner Of War Camp, Algona Iowa 4 November 1944 Re: German Prisoner Of War Heinz Schymalla” Archived by Camp Algona. November 1944.

Colonel Lobdell. “Transcript Of Testimony Taken At Hearing At Prisoner Of War Camp, Algona Iowa 4 November 1944 Re: German Prisoner Of War Walter Mai” Archived by Camp Algona. November 1944.

Hawke, Rosella. “Cut Foot Sioux Camp F-14 Prisoner of War Camp.” Herald-Review, Grand Rapids, 18 Nov. 1999.

Secondary Sources

Pluth, Edward. “Prisoner of War Employment in Minnesota During World War II.” Minnesota History. Winter 1975.

Macklin, Bill. “German POW’s in Minnesota Never Had It So Good.” The Pilot – Independant, 10 Oct. 1985.

Minneapolis Morning Tribune “Two Escaped Nazi Prisoners Caught” Minneapolis Morning Tribune November 4 1944. (author not listed)

Lemen, Bob . “Shooting the Rapids.” Herald-Review, 22 May 1972.

Lobdell, George. “Minnesota’s 1944 PW Escape” Minnesota History. Fall 1994 (note George Lobdell is the son of Colonel Lobdell in primary sources)

Itasca County Historical Society. “Civilian Conservation Corps 1933-1942” Civilian Conservation Corps Alumni. Compiled 2017

Yockelson, Mitchel. The War Department: Keeper of Our Nation’s Enemy Aliens During World War I. Society for Military History, Apr. 1997, net.lib.byu.edu/~rdh7/wwi/comment/yockel.htm.