The Battle of Lundy’s Lane took place during the War of 1812 in Niagara Falls, ON Canada. The Battle of Lundy’s Lane is widely considered the bloodiest battle during the War of 1812, and the bloodiest battle ever fought in Canada. The battle was a draw in tactical terms, but is widely considered to be a British strategic victory do to the large casualties done to the American side. It is remembered by the people of Canada to this day.

Background Information

The United States army during the war of 1812 was mediocre at its best. We had only accepted the constitution a few decades before the war broke out, and we were going to fight the largest army in the world at the time. Britain was in control of Canada during the 1800’s, and the young America wanted more land. The opportunity arose when Napoleon Bonapard declared war on Britain in an effort to expand France. We had gathered the troops, which had basically consisted of state militias, and prepared to fight the British in Canada. We declared war in 1812, which lead to the name of this war, The War of 1812. Two years later, America showed minimal land conquered in Canada besides a bit West of New York, and the British had defeated Napoleon in Europe. Before the battle of Lundy’s Lane, the Americans had just had an overwhelming victory at Chippewa. It was the first major victory the Americans had over the British (Bonura).

The Niagara force of the American army at the time was led by Generals Scott and Brown, where Scott is remembered for combining British and French styles of warfare to create one of America’s best forces. “In a little over two months, Scott turned Brown’s 3,500 men into the best trained and disciplined American army of the war.” (Bonura, pg 10). Scott trained his men in Buffalo to prepare for the campaign to gain more ground West of New York, namely to force the British away from Fort George. Scott’s men presumably thought very highly of him, and were overly confident leading into Lundy’s Lane (Clough). After the victory in Chippewa, Scott’s forces were sent North under orders of General Brown. The brigade, consisting of the Ninth, Eleventh, Twenty-second, and Twenty-fifth Regiments, marched up the Niagara River to gain ground on the British (Emerson). The British, led by Lieutenant General Drummond, marched down the river to meet the American forces head on.

At this point in the war, the British forces were not particularly happy about the war. They were fighting far from home, and continuing to fight after they had just defeated Napoleon left them worn out. They had just taken Fort George back from the Americans, however it wasn’t in great condition. The Fort was reclaimed at the start of winter, so the American’s took “preparations” before the British arrived. They had abandoned the fort, leaving it stripped of its doors and windows allowing cold and snow in, and set fire to the surrounding farmland. The city of Niagara was also burned badly, against General Brown’s orders. The British force had to stay at the fort for the winter, were countless deserters fled both due to lack of food and warmth and being frustrated for not receiving pay (Cruikshank). The desertions died down as the weather warmed up, and the British navy was able to arrive at the fort with Lieutenant General Drummond. Drummond planned to retake the land lost to the Americans and force them out of Canada.

The Battle

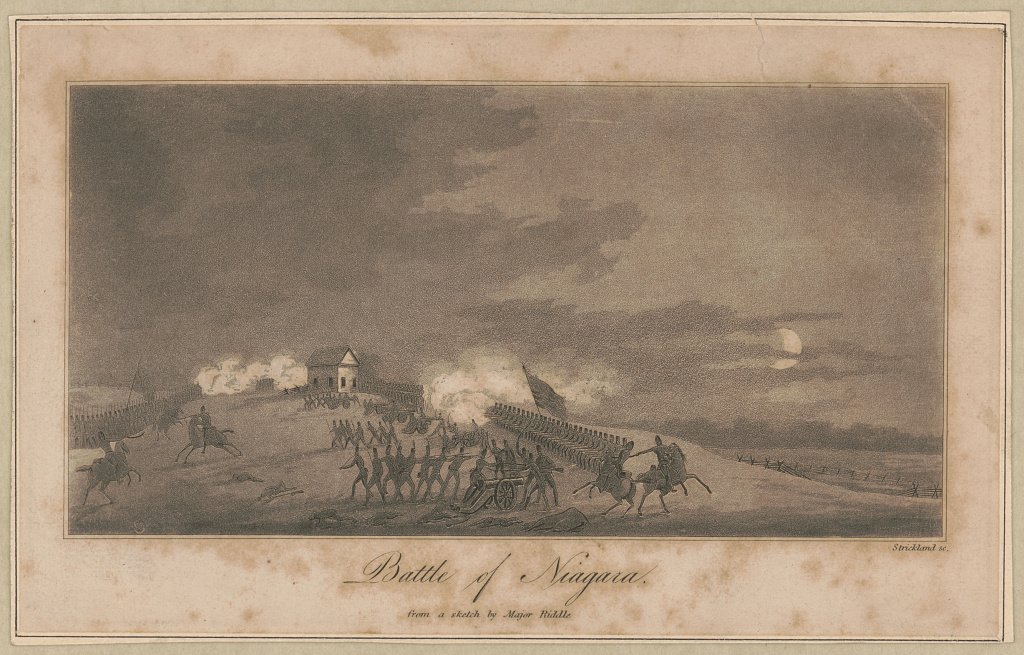

The two opposing forces met on the battlefield on the corner of Lundy’s Lane and Hanan Ave for a massive battle. The British, having a force of roughly thirty-five hundred men lined up with cavalierly in the center of the formation, took a position at the top of a nearby hill and set up artillery cannons adjacent to them to pelt the Americans with (Anderson). The Americans had a force of roughly 2500 lined up with the Eleventh on the left, Twenty-second in the middle, and the Ninth on the right with cannons next to the Ninth (Emerson). Scott’s forces arrived and were greeted with British cannon fire. The Americans having the low ground and being bombarded created a large issue, namely how to get the British off the hill so they could fight them. Scott turned to the commander of the Twenty-fifth brigade, led by Colonial Miller, to take the British guns in what is stated to be the bravest move the American forces made during the war. Upon hearing his orders, Col. Miller famously stated “I’ll try sir.” The Twenty-fifth then flanked the British and took the cannons, since the British had left them with little protection, and turned the British guns to fire on the hill the British had fortified. This freed the hill for the Americans to take (Anderson).

The fight over the British artillery cannons was the key reason this battle was so bloody. Controlling those cannons became the main tactical goal on both sides, for a few key reasons. One, they were state of the art military weapons capable of destroying an army. And two, they were in a terrible defensive position, making it easy to gain or lose them at a moments notice (Emerson). The British charged the cannons, forcing the Americans defending them to retreat. Then, the Americans regrouped and charged the cannons allowing them to be retaken. This back and forth went on for several hours (Brady):

At times the lines approached within a few yards of each other and fired directly into each other’s faces. It is even claimed that there was hand to hand fighting over the guns in the effort both to capture by the Americans and to retake them, by the British.

(Emerson, pg 64- 65)

The British eventually did gain control over the cannons, and hauled them away from the battlefield to avoid the Americans capturing them for good (Anderson). The battle continued well into the night after this, with men fighting at bayonet point on top of the hill (Anderson) and firing at muzzle flashes since it was a cloudy day and there was no light (Brady).

Throughout the entirety of the battle, Scott and his forces were known for being more or less unmoveable (Emerson). Scott had used a combination of both British and French warfare to make his troops an elite fighting unit (as stated previously), and their sheer stubborn tenacity is what allowed him to press on. Since the Eleventh and Twenty-second regiment had both been so badly damaged, the remaining forces were recombined with the Ninth on the second day of fighting (Emerson). The Americans also received reinforcements in the form of General Brown’s brigade. While Brown attempted to force the British into submission, Scott and his force lined up and flanked the British. This turned out to be a disastrously bad idea, as now Scotts forces were fired upon by both the British and the Americans who couldn’t tell the forces apart (Cruikshank). The battle eventually dissolved into the chaos of the previous day, with both sides fighting with bayonets or event their fists. In this madness, every commanding officer on the American and British side were wounded mortally, and forced to retreat. Scott and Brown both had to be rushed back to Buffalo to be treated for their injuries (Brady). General Drummond remained on the battlefield, leading his troops into battle and charging despite having a bullet lodged in the side of his neck (Anderson). During the chaos on the second day, the Americans were able to capture a regiment of the British forces, including their leader Captain Loring (Anderson). Both forces were forced to retreat from the area, with the Americans returning all the way to headquarters in Fort Erie. The British were then able to advance past Lundy’s Lane to attack Fort Erie (Brady).

The Aftermath

The Battle of Lundy’s Lane proved to be extremely bloody for several reasons. Firstly, the fighting over the British artillery cannons was long and intense. The repeated charging under cannon fire, as well as how many charges were likely repealed on both sides without being documented, lead to large deaths on each side. The maneuver Scott executed towards the end of the battle, attempting to flank the British troops, resulted in several deaths. The total casualty count is estimated on the American side to be eight hundred fifty-three men. Of that, one hundred seventy-four were killed, five hundred seventy-three were wounded, and one hundred seven were captured or missing. Comparing this to the British side, eight hundred seventy-eight casualties were sustained, with only eighty-four killed, five hundred fifty-nine were wounded, and two hundred twenty-four missing or captured (American Battlefield Trust). Seeing these numbers, it is easy to see why the Americans are considered the losers of the Battle of Lundy’s Lane. The British were able to force the Americans out of Canada and eventually win the war of 1812.

General Scott and his brigade went down in history as some of the toughest soldiers the US had ever seen, despite Scott’s young age. Scott became famous for several years, eventually rising up the ranks of the United States military (Emerson).

Like all noted men, Scott had his peculiarities – we may even call them weaknesses, but no man ever yet questioned his courage or disputed the claim that he was brave even to recklessness.

(Emerson, pg 65)

The Battle of Lundy’s Lane was hard fought and left a trail of blood in its wake, but went down in history as a courageous fight from both sides, still remembered by the people in the Niagara region of Canada.

Primary Sources

- Clough, Chase (1814).Letter – American soldier’s account of battles at Chippewa, Lundy’s Lane and Fort Erie.

- Anderson, Charles (1840). A True and Impartial Account of the Actions Fought at Chippawa & Lundy’s Lane During the Last War with the United States.

- Cruikshank, Ernest (1893). The Battle of Lundy’s Lane, 35th July, 1814: A Historical Study.

Secondary Sources

- American Battlefield Trust (2019) Lundy’s Lane, Niagara Falls

- Emerson, George Douglas (1909). General Scott at Lundy’s Lane.

- Brady, William Y. (1949). The 22nd Regiment in the War of 1812

- Bonura, Michael A. (2014). A French Inspired Way of War: French Influence on the US Army from 1812 to the Mexican War.