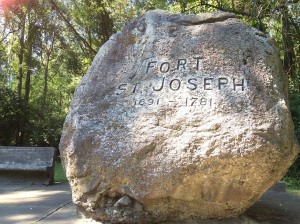

Fort St. Joseph was a trading post built by the French on the bank of the St. Joseph river near present day Niles, MI. The land was originally given to the Jesuits in 1684 by the French crown in order to build a mission. In 1691 Ensign Augustin Legardeur de Courtemache was sent to build a military post near the mission. Eventually Europe’s growing animal fur demand pushed traders to the area and the fort was used as a trading post for French traders and Native Americans. After the French and Indian war, the fort was handed over to the British. Natives did not enjoy life under the British and revolted in Pontiac’s rebellion. The fort was quickly taken, but the rebellion lost steam and the fort was never garrisoned again.

French Jesuit priests became fairly prevalent in and around the St. Joseph river basin during the 17 and 18th century building missions all over the great lakes region that would later become important trading hubs. Missionaries of the society of Jesus would travel to Indian villages and attempt to convert them. Father Gabriel Marest, a missionary traveling traveling in western Michigan, said, “Nothing is more difficult than the conversion of these Indians; it is a miracle of the Lord’s mercy. It is necessary first to transform them into men, and afterwards to labor to make them Christians.”[1] The Father later describes them as lazy, thievish, and deceitful, and only through the grace of God will they be converted. Despite Father Marest’s views of the Indians, the natives got along relatively well with the French and allowed them to build small military outposts near the missions.

The fort was fairly small, with about 15 houses in and around the fort accommodating about 10 enlisted men and 20 soldiers. There was also a blacksmith, a priest, and an interpreter. Fort St. Joseph, along with many similar forts in the area, did not hold much military value. The land was harsh and underdeveloped, few europeans lived in the area full time. The fort instead formed the backbone of the French fur trade.

Fur clothing had become very fashionable in Europe in the sixteenth century. A nice fur hat and coat were the ultimate symbol of wealth and status. Various animal pelts were used but the highest quality clothing was made from beaver pelt. But the huge demand that had been generated drove beaver populations in Europe to near extinction. Fur trappers turned to the new world to feed Europe’s hunger for furs.

French traders relied on Natives to get the furs and traded them for European manufactured goods such as muskets, knives, and kettles. In order to maintain French dominance in fur in the area, The French generally treated Indians with respect, often giving gifts in order to build a positive relationship. Forts along the frontier like fort St. Joseph became intermediate point for traders and Indians. As well as hubs for communication as supplies for the fur trade.

By the early 1700’s the French began to feel pressure from another European force. Farmers from the British colonies to the east were anxious to press past the appalachian mountains and the Hudson Bay Company, a British fur trading company that had a monopoly on the fur trade south of Hudson bay. French policy turned from making money to maintaining control of French Canada and the great lakes region. In order to do this, they strengthened alliances with Indian tribes, supplying them with ammunitions, and preparing them for war.

After the French and Indian war, Fort St, Joseph along with other French forts, were handed over to the British and a detachment of the 60th Royal American Regiment garrisoned the post in 1761. However it started to become clear to the natives that the british occupation was going to work very differently than the French occupation had. The British stopped the practice of gift giving and generally saw the Indians as more difficult than the French did. According to British commander Amherst,

“I do not see why the Crown should be put to that expense. Services must be rewarded; it has ever been a maxim with me. But as to purchasing the good behavior either of Indians or any others, [that] is what I do not understand. When men of whatsoever race behave ill, they should be punished but not bribed.”[2]

The Indians saw this as a step toward the British taking their land, which their French allies warned them about. Talks of war began to circle the tribes. By the summer of 1761 war belts, belts sent from one tribe to another when asking for help in a war, were being passed among the tribes. Chief Pontiac of the Ottawa was gathering support from the Potawatomis and Hurons as well as tribes in Pennsylvania and Ohio. The British learned of this plan and reinforced fort Detroit, but left the smaller forts like fort St. Joseph with their small detachments. In the spring of 1763 Potawatomi warriors stormed fort St. Joseph, killing all British soldiers except for the commander. The attack in Detroit did not go quite so well, resulting in a long siege and ultimate failure to capture the fort. The rebellion petered out after that and the British reclaimed fort St. Joseph, but never permanently garrisoned it again. French trappers continued to use the fort to trade with local Indians.

In 1780, Patrick Sinclair, British commander at Fort Michilimackinac decided to rid Fort St. Joseph of its French inhabitants and captured the fort. The land was still British territory, but the vast expanses of wilderness and lack of supervision meant French traders could use the fort to conduct business, as there were no British soldiers around. Sinclair put a stop to this allowing British traders to use the fort. British traders used it until later that year when a French officer captured the fort and its British traders with little resistance.

In early 1781 a group of French and Indians looking to avenge English Grievances in the St. Louis area approached the Spanish Governor Francisco Cruzat and asked him to authorize an attack on Fort St. Joseph. The Governor thought control of the fort would diminish British control in the region and gave the party permission to attack. The attack was successful and the spanish flag was raised over the fort, claiming the region for the king of spain, however the party left the next day. This is why Niles, Michigan claims to be the city of four flags, because the area was occupied by four nations, France, England, Spain, and the United States.

The fort remained under British control until 1795 when Jay’s treaty was signed and the British withdrew from the midwest. The fort was forgotten and left to ruin and completely gone by the time American settlers arrived in Niles in the 1820’s. A historical marker was placed at the presumed location in 1957, but the actual location wasn’t discovered until 1998 by archeologist from Western Michigan University.

Primary Sources

- Kip, William Ingraham. The Early Jesuit Missions in North America. New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1846.

- Utley, Robert M., Wilcomb E. Washburn, and Robert M. Utley. The Indian Wars. New York: American Heritage, 1985.

Secondary Sources

- “Fort History.” Western Michigan University. Fort St. Joseph Archaeological Project, 2016.

- Myers, Robert C. “Historic Sites: Fort St. Joseph.” Fort St. Joseph. North West Territory Alliance, Mar. 1996.

- “Fort St. Joseph Site.” Detroit 1701. Detroit1701, June 2010.

- Nassaney, Michael S. “Reclaiming French Heritage at Fort St. Joseph in Niles, Michigan.” Encyclopedia of French Cultural Heritage in North America. University Laval, 2007.

- Nassaney, Michael S., et al. “THE SEARCH FOR FORT ST. JOSEPH (1691-1781) IN NILES, MICHIGAN.” Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology, MCJA, vol. 28, no. 2, 2003., pp. 107-144

- “Economic Activities.” Fur Trade | Virtual Museum of New France. Canadian Museum of History, n.d. Web. 18 Nov. 2016.