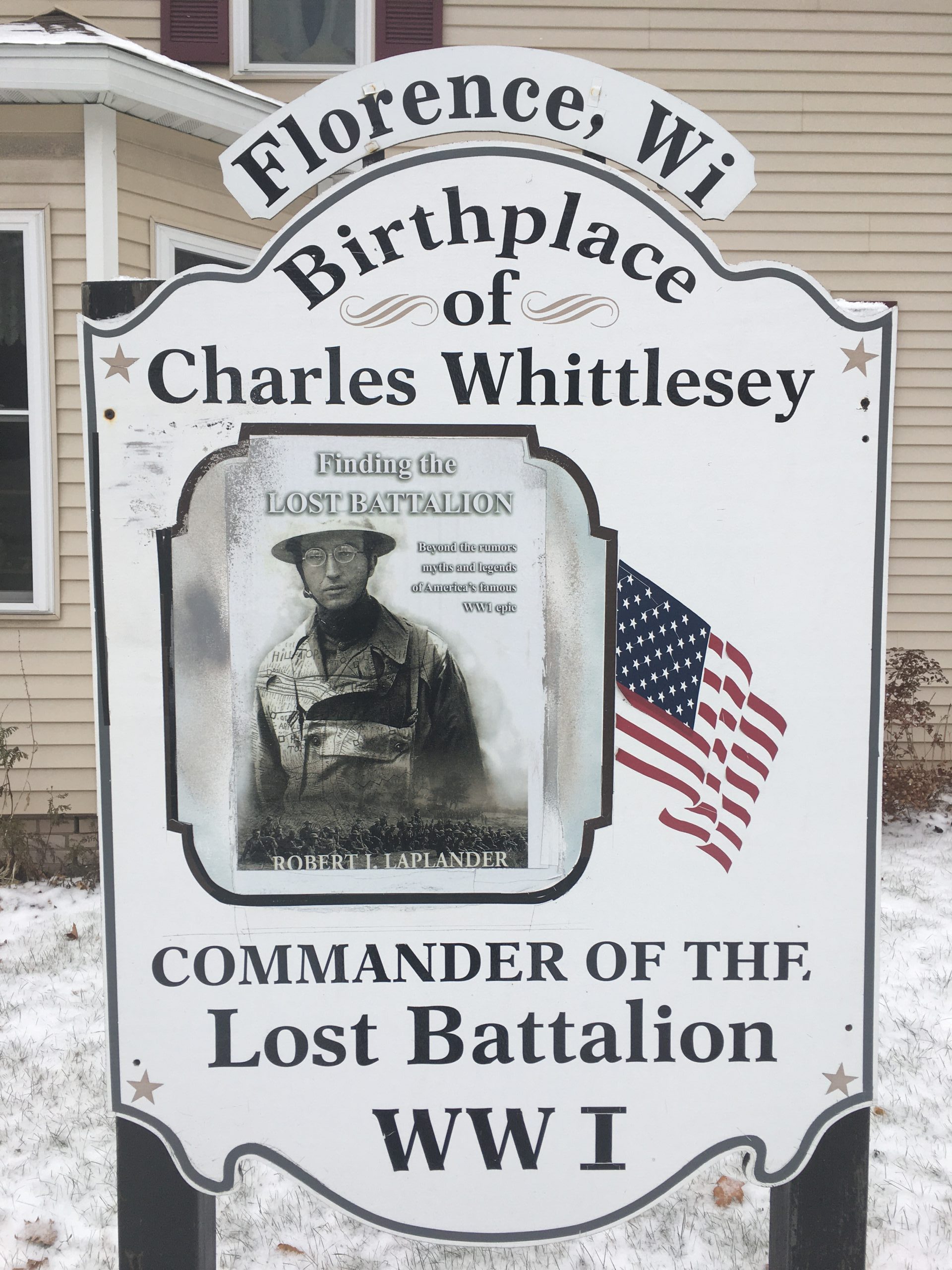

For five days in October of 1918, near the end of World War I, the 308th Infantry Battalion were cut off from the rest of their 77th Division during an offensive against the Germans in the Argonne Forest. Leading them was Major Charles W. Whittlesey, a Harvard Law graduate and former New York City lawyer who was called into active duty on August 8th, 1917. Born and raised in Florence, Wisconsin, Whittlesey returned from this ordeal a war hero with a national celebrity presence. However, his story ended in tragedy, with his suicide on November 26th, 1921. This story exemplifies the importance of working with veterans and helping to maintain their well-being once they return home, an idea hardly even thought of in the early 20th century, and one too easily forgotten in modern times.

Early Life

Whittlesey was born in Florence, Wisconsin on January 20th, 1884. He lived in Northern Wisconsin until 1894, when his family moved to Pittsfield, Massachusetts. He graduated from high school in 1901 and went on to attend Williams College. After graduating from Williams in 1905, and from there went on to Harvard Law School. After graduating from Harvard in 1908, he started a law firm in New York City and worked there until joining the Army in May 1917 a month after America’s entry into World War One. He was sent to Europe as Captain and was eventually promoted to the rank of Major.

Events of the War

The offensive which earned Whittlesey infamy began on October 2nd, 1918, when Whittlesey and his battalion were ordered to advance forward on the Germans in the Argonne Forest. They were commanded to reach a certain point within the forest, which they were able to accomplish. Unfortunately, other battalions also ordered to advance did not make the same progress as the 308th did, and German machine-gun nests cut off Whittlesey’s forces from the rest of the Allies. With limited rations, many men either killed in action or wounded, and nowhere to go, the situation was dire. Along with this, their only communications options were homing pigeons to try to give their position to Allied troops to receive help. The first homing pigeon that arrived unfortunately gave the wrong coordinates and Whittlesey and his troops were pelted by friendly fire air support. This continued until a second homing pigeon was able to deliver instructions to stop with the air support from the Allies. After the fourth day, the German commander tried to get the Americans to surrender, a message that Whittlesey scoffed at. On the fifth day, the advancing Allied forces were able to locate the trapped troops and relieve them. These troops returned home as war heroes and the 308th Battalion came to be known as the Lost Battalion.

Life After the War

Following the war, Whittlesey tried to move on with his life, going back to his law practice to try to pick up his life where he left it. He then took a job in late 1919 serving in the Red Cross Roll Call. This put him in a position to try to help many of his former comrades in there struggles since returning to civilian life, both physical and emotional. Unfortunately, this exacerbated already troubling difficulties he was facing. Along with the newfound stresses of a life in the public eye since his return home, he was also having a difficult time overcoming his own demons from his time overseas. While he spent his time trying to get his life back to normal, he faced constant reminders of his ordeals from several different fronts. The first was the numerous public events he was asked to do, which included ceremonies, public forums, and media ventures. The second was through repeated interview requests, which he mostly declined. In a 1920 publication of Everybody’s Magazine, a former soldier under his command, Lieutenant Arthur McKeogh, wrote a lengthy article about Whittlesey and their time together over that five-day period. Although Mckeogh focused on points that Whittlesey probably would have approved of, including debunking the myth that Whittlesey told the German soldiers to, “Go to hell!”, when they asked for his surrender, Whittlesey repeatedly told McKeogh to not write about him and instead about the group of men as a whole. The third and likely most damaging factor that contributed to Whittlesey’s struggles was his soldiers continued requests for guidance and aid in overcoming their ordeals from the war, when he himself was still facing those challenges. The constant need of his former battalion members to come to him continuously reminded him of the horrific sights he saw, therefore hindering his ability to make peace with what he lived through and move on.

These factors drove him to a desperate place mentally, one which he could never pull out of. However, that didn’t stop him from performing his duties. He acted has pallbearer for the Unknown Soldier in late November 1921. A few days later, he boarded the SS Toloa, a United Fruit Company ship set to sail from New York City to Havana, Cuba. On the first night of the voyage on November 26th, 1921, he left the smoking area of the ship to go to his room and was never seen or heard from again. He had established a will right before he left the city and left several notes to friends and family in his cabin. It was an unfortunate end to a brave American hero’s story, and one, due to the way of the times, that was largely unavoidable. Since then, conditions for returning veterans has greatly improved and the mental health field has a much better grasp on what former soldiers are going through once they return home. Still, there are lapses in the way America handles these soldiers once they return home.

Treatment of Whittlesey and Veterans as a Whole

By all accounts, Whittlesey suffered from the same ailments that our veterans face as they return home today. He suffered with sleepless and restless nights, tormented by the screams of the wounded and suffering he had heard during the war. He seemed stuck in a rut, consistently moody and glum over his last few years. No doubt, Whittlesey would have been diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder or some similar illness based on the symptoms he was feeling, along with a diagnosis of depression. However, the climate of the age didn’t allow for that to happen. People didn’t fully understand mental health yet, and weren’t sure how to comprehend what would be going through someone like Whittlesey’s mind. Instead, he was put up on a pedestal, cheered on as a hero who had fought the good fight, returned home, and would no doubt come back and continue living his successful life. Many didn’t understand why he so disliked events honoring him which focused on his military service. They believed they were doing what they were supposed to do with a war hero. With new medical knowledge on what he was going through, Whittlesey would have probably been treated very differently in this day and age. Of course, he still would have been celebrated as a hero, but not in the continuous and laborious fashion that he was in post-World War One times. His needs and wishes assuredly would have came first over public speaking events and ceremonies. He also wouldn’t have been pushed into the position of caretaker, psychiatrist, and mentor to those who served under him if he had not been ready to do so. There are many different organizations now who are ran by former soldiers who reach out and help veterans in need, but these are ran by people who are in a good place mentally, and feel comfortable reaching out and being that person to lean on for their comrades who are not as well suited to life back in the United States. Instead, he was considered the brave commander who had led his men through the treacherous ordeal and could tackle any challenge in front of him. He felt pressured to volunteer as this counselor to former soldiers, who overworked himself in doing so and ran himself ragged. He visited men in hospitals, he helped try to get them help for their lingering physical wounds, he attended funerals, served in funerals, and essentially anything else that was asked of him in this regard. All the while he felt the burden of his own problems continuously mounting up. This lack of concern for his well-being, from himself, the people around him, the media, and the nation as a whole, was a driving factor in his decision to take his own life in November of 1921.

To this day, the images people think of when talking about the end of the World Wars are those of people celebrating in the streets, with soldiers returning home triumphant and jovial. Young men returning home happily to their lives, whether that be a girl, a job, or just simply to be done fighting a foreign war. What can be clearly seen with the case of Major Whittlesey, however, is that history lessons and documentaries have left out a large part of the story. They left out that after the celebrations had ended, and the cameras had stopped rolling, these men were left to deal with what they experienced overseas. That lack of awareness continued through until after the Vietnam War, and even then, many people considered the situation to be an isolated incident specific to that conflict. Thankfully, much progress has been made since then, with not just the treatment of the physical well-being, but the psychological well-being of the returning soldiers being prioritized. However, there is still work to be done. Even now, with the treatment of veterans an often talked about campaign issue, and political parties putting importance on what they are perceived to be doing to help former combat soldiers, there are still missteps. Just recently, there were scandals involving the Veteran’s Affairs hospitals around the nation and their ability to treat former soldiers. It appeared as though a lack of allocation of funds towards these hospitals contributed to these failures.

If there might be one thing to learn from the tragic tale of Charles Whittlesey, it is that just because someone holds it all together in the face of an enemy across a battlefield, that does not mean that they will be able to face the enemy of themselves and their own mind once they return home. And while Charles Whittlesey is a famous case that can be pointed to and elaborated on, imagine the countless soldiers that also face these same challenges, but have gone unnoticed. It is the duty of the United States as a government, and as citizens of the United States, to look out for these veterans in their time of need, just like they looked out for our nation in its time of need. They served us overseas, once they return home is our time to serve them.

Primary Sources

- Garey, E. B., et al. American Guide Book to France and Its Battlefields. The Macmillan Company, 1920.

- McKeogh, Arthur. “Whittlesey’s Other Answers.” Everybody’s Magazine, Apr. 1919, pp. 65–101.

- Reynolds, Francis J., et al. The Story of the Great War: History of the European War from Official Sources: Complete Historical Records of Events to Date. Vol. 8, P.F. Collier and Son, 1920.

Secondary Sources

- “Charles Whittlesey Commander of the Lost Battalion.” Charles Whittlesey – Commander of the Lost Battalion

- “The Lost Battalion.” IMDb, IMDb

- “Medal Of Honor.” CMOHS.org – Major WHITTLESEY, CHARLES W., U.S. Army, Congressional Medal of Honor Society, 2019

- Parnass, Larry. “On Veterans Day, a Lost Battalion. A War Hero. And a Heartbreaking Suicide.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 1 Apr. 2019

- Welker, Kevin. “The Tragedy of Heroism: Charles W. Whittlesey.” The Tragedy of Heroism: Charles W. Whittlesey – Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Society of the Honor Guard: Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, 1 Dec. 2013

- Langeveld, Martin C. “Missing in Action: Charles W. Whittlesey’s Farewell.” The Monday Evening Club, 9 Mar. 2009

For Further Reading

- Major Charles W. Whittlesey (Wikipedia)

- The Lost Battalion (Movie, 1919)

- The Lost Battalion (Movie, 2001)

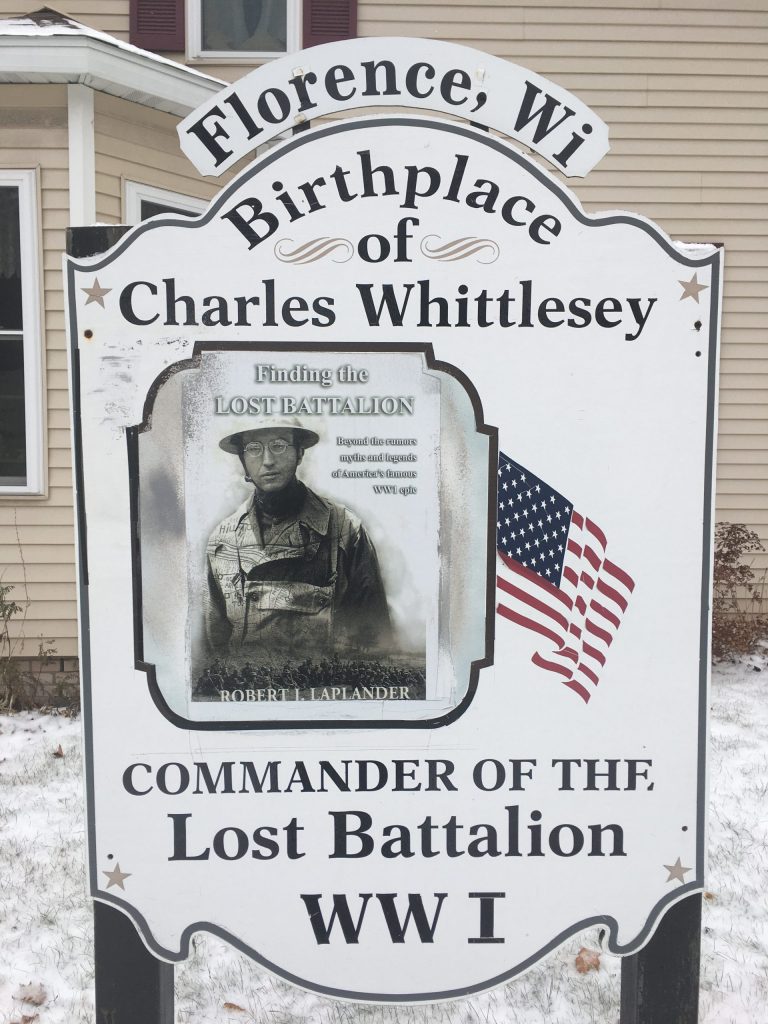

- Finding the Lost Battalion (Book, 2006)