Solon Spenser Beman and Nathan F. Barrett designed George Pullman’s factory and community, starting in 1879. Beman designed the buildings and Barrett the landscaping and organization. When construction began, Barrett laid out the footprints while Beman supervised construction through a bonanza-like rush of building between May of 1880 and April of 1882. Stanly Buder (1967:49-59) summarized the fantastical rate and scale of the operation, widely reported in newspapers and magazines. Dr. Buder quoted draftsman Irving Pond’s recollection that the design and revision process happened so quickly that staff often fleshed out plan details on the the floors of buildings as they were being built. Beman found the process exhausting and he took a break in January of 1881, taking time to travel to his New York home.

These events interest us for several reasons. First, this gives a good window on the social process of creating the factory and town. The effort required the coordinated creative labor of hundreds of people and as such, we must learn to see a building like the Palace Car Erecting Shop as the realization of the collective vision of many people, including the architect but also the masons, ironworkers, carpenters, machinists, brickmakers, and so on, as well as the people who lived and worked in these spaces. The material evidence of this collective creativity is fossilized in the masonry, concrete, and organization of the works.

Second, and more urgent for the current study, is that the material evidence provides unique evidence about the design process. A workplace may be designed by one person; built by another; inhabited, used, revised by a third; and redesigned and rebuilt by still another. The physical remains often reveal clues as to how that process occurred. Because the material evidence is independent of what people wrote about the design, it adds a new stream of evidence to counterbalance textual and photographic sources as we tell the stories of the Pullman factory.

Very few architects had designed factories in 1879 and 1880. The process by which S. S. Beman and George Pullman interacted to design the factory is known in outline, but not detail. Beman was 27 years old when he won this commission, experienced in residential structure design. Beman had never designed a factory, however. Most architects considered industrial architecture to be beneath the aesthetic missions of their field. So how did Solon arrive at his design?

This is really important, since both the architect and the owner invested so much in this idea. The Pullman factory and community were an experiment intended to do nothing less than transform the practice of industrial capitalism. For his part, George Pullman claimed that the design of the factory (and the town) was a logical extension of the “Pullman System”: beautiful/quality, ordered, functional, scale, and consistency. Many of these themes would have resonated with an architect at this time.

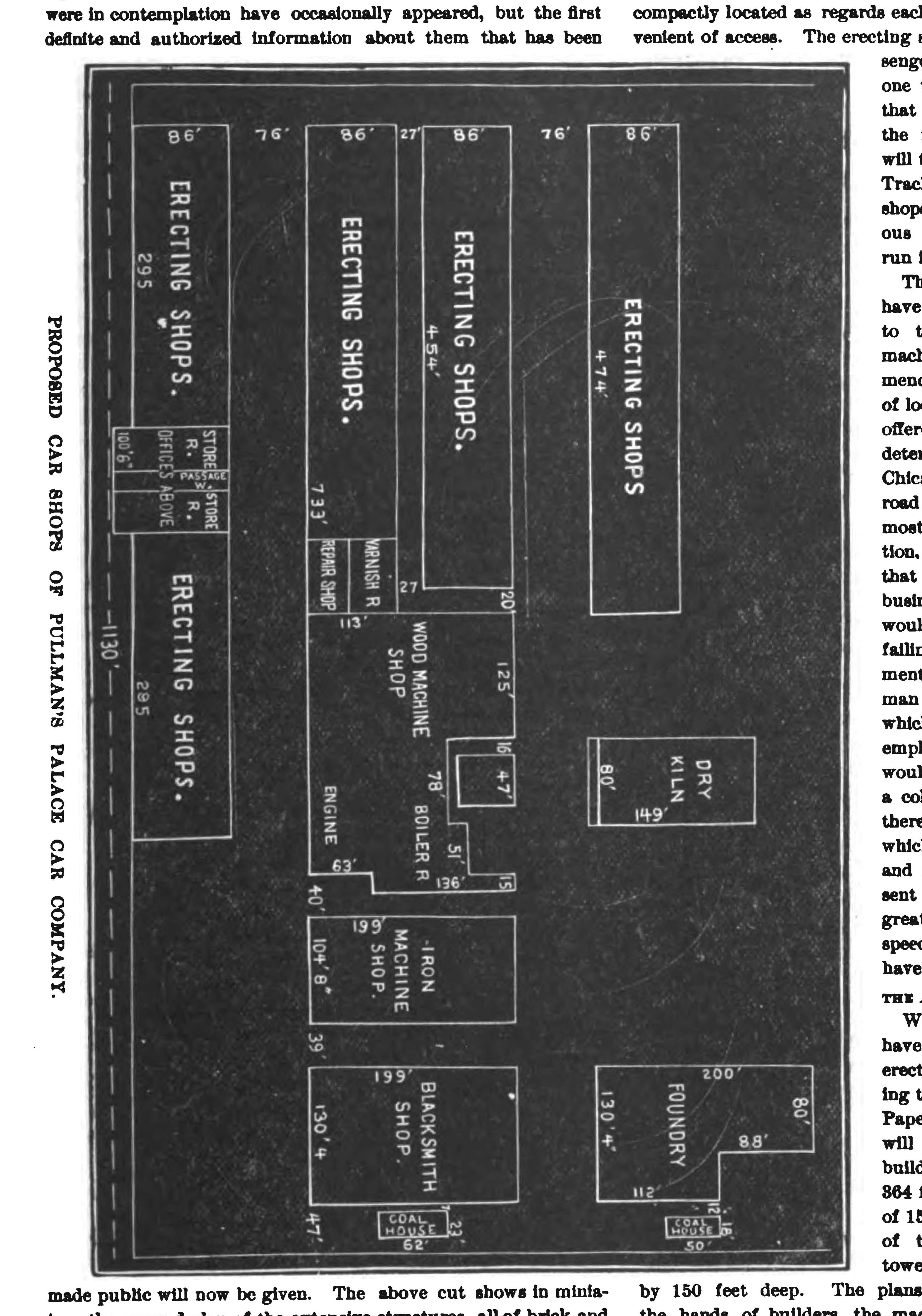

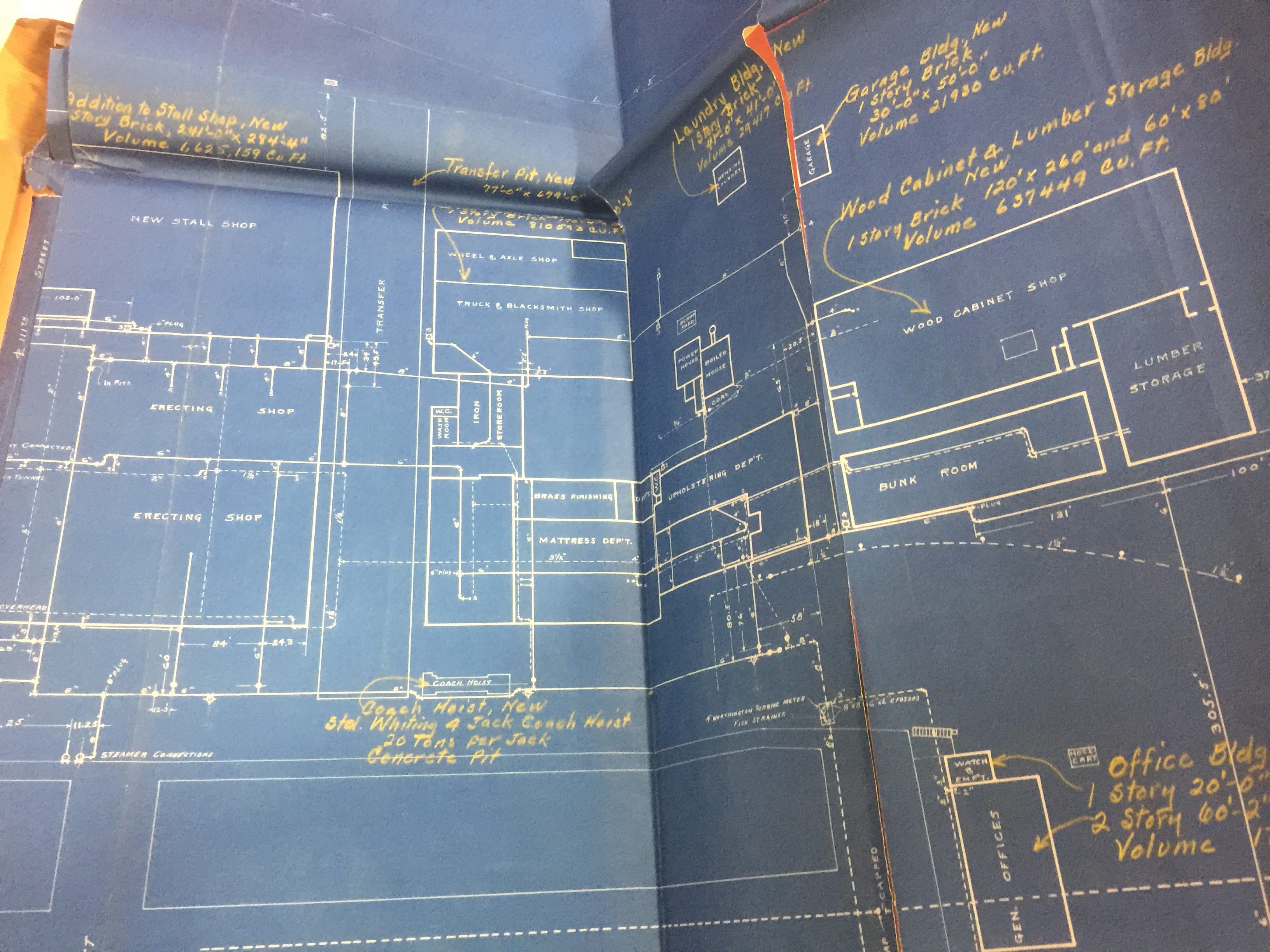

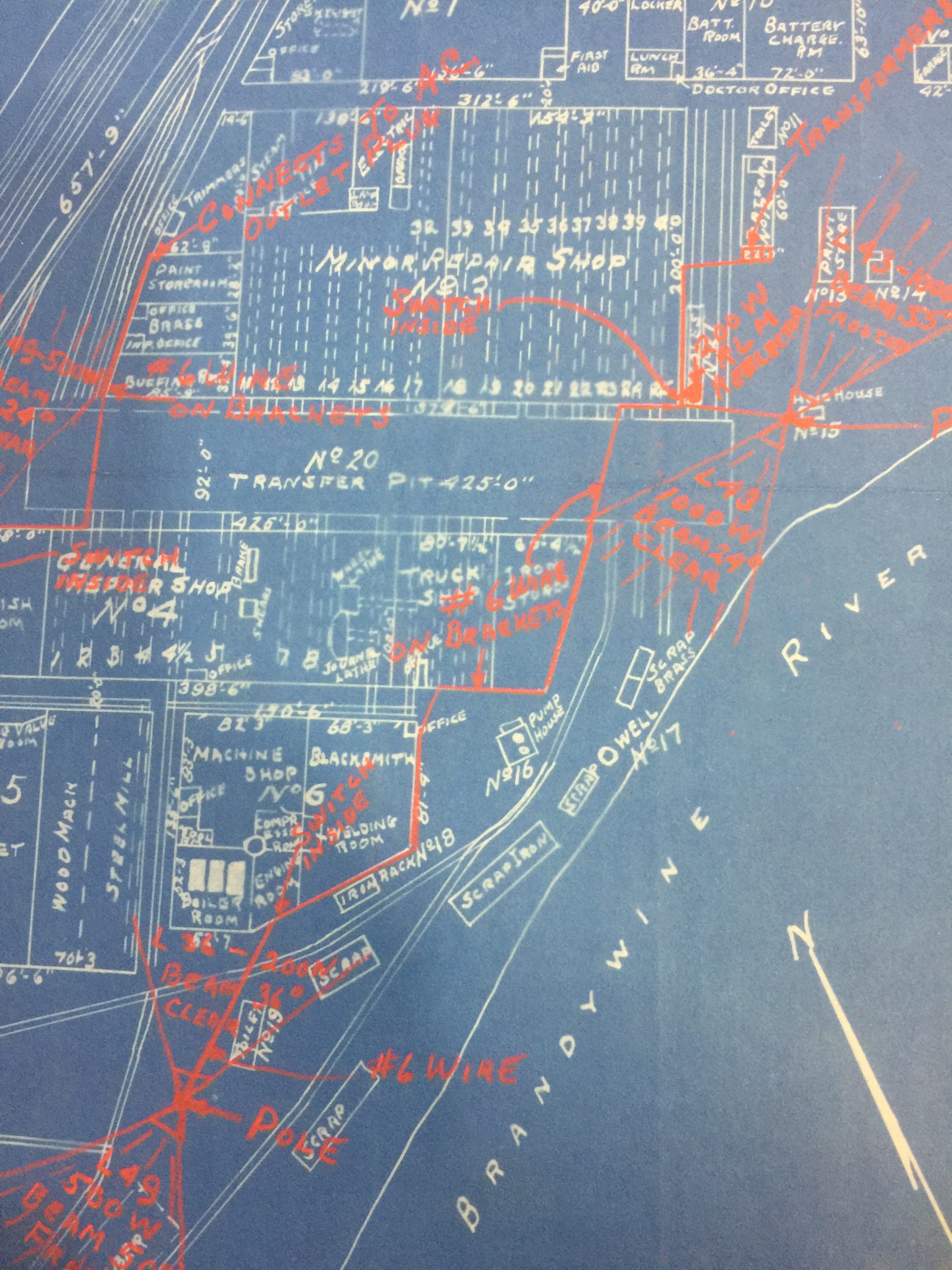

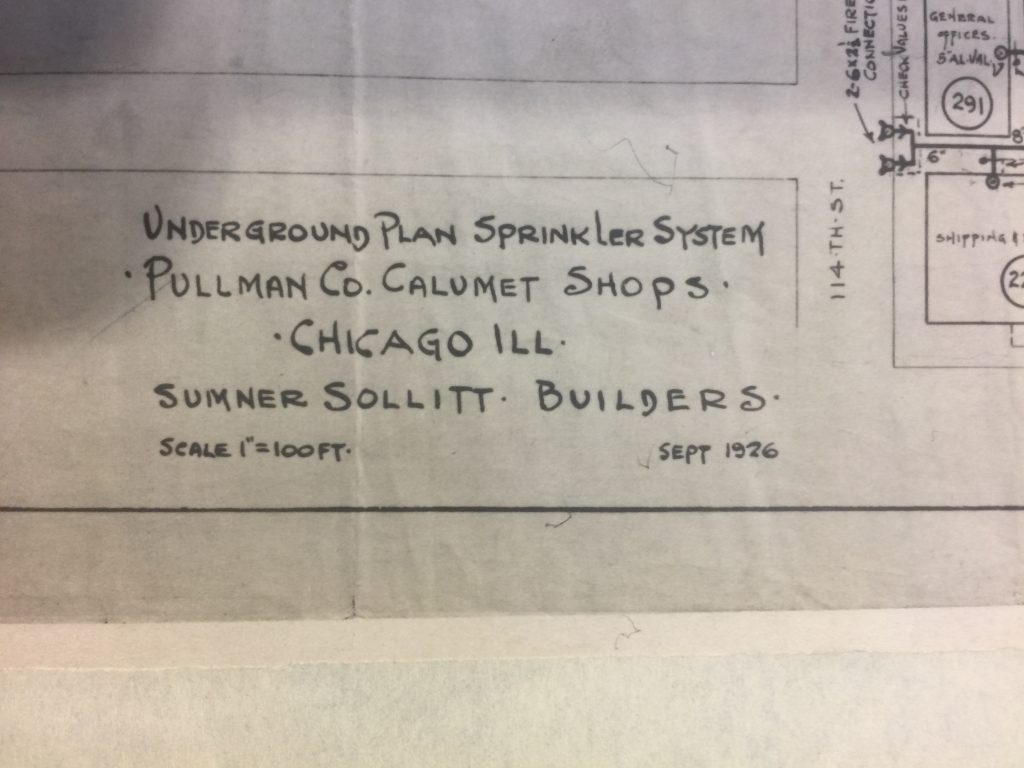

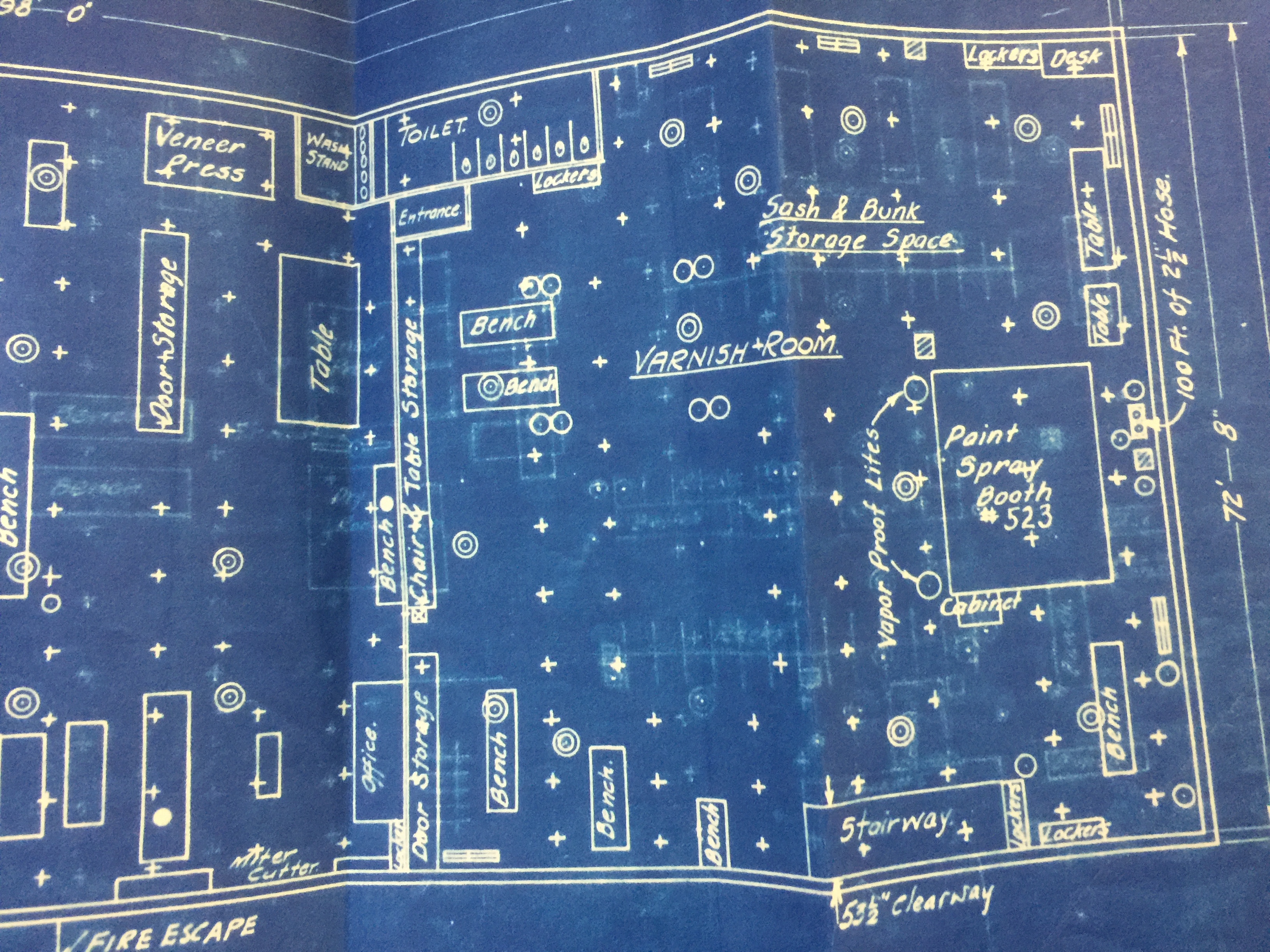

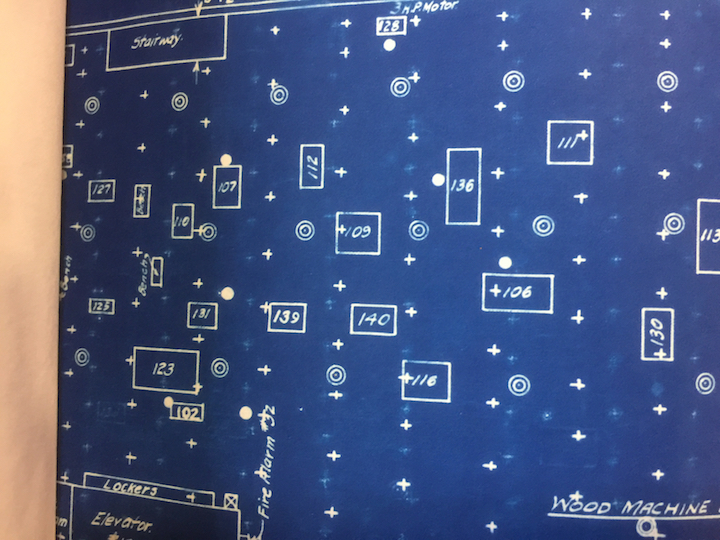

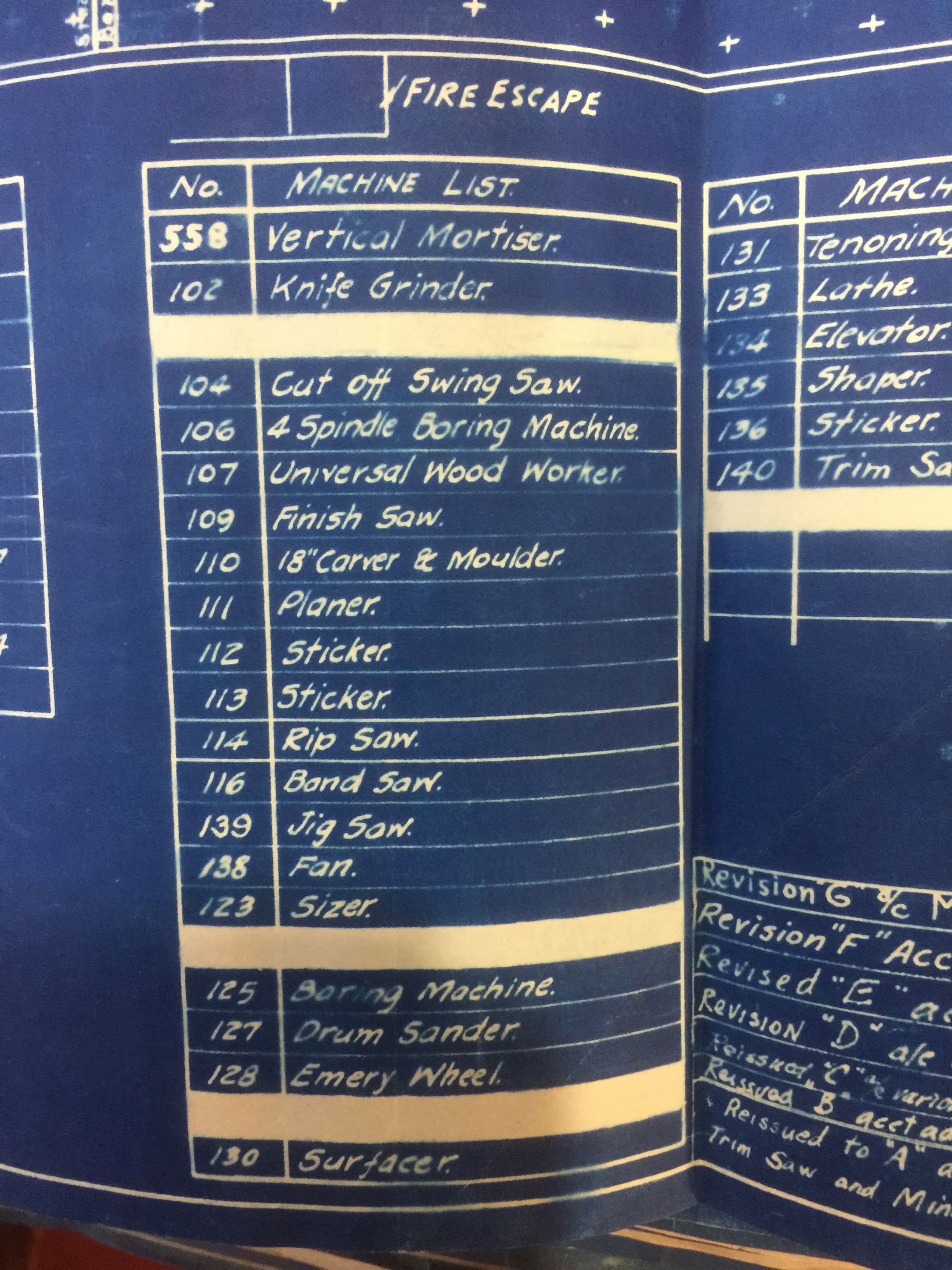

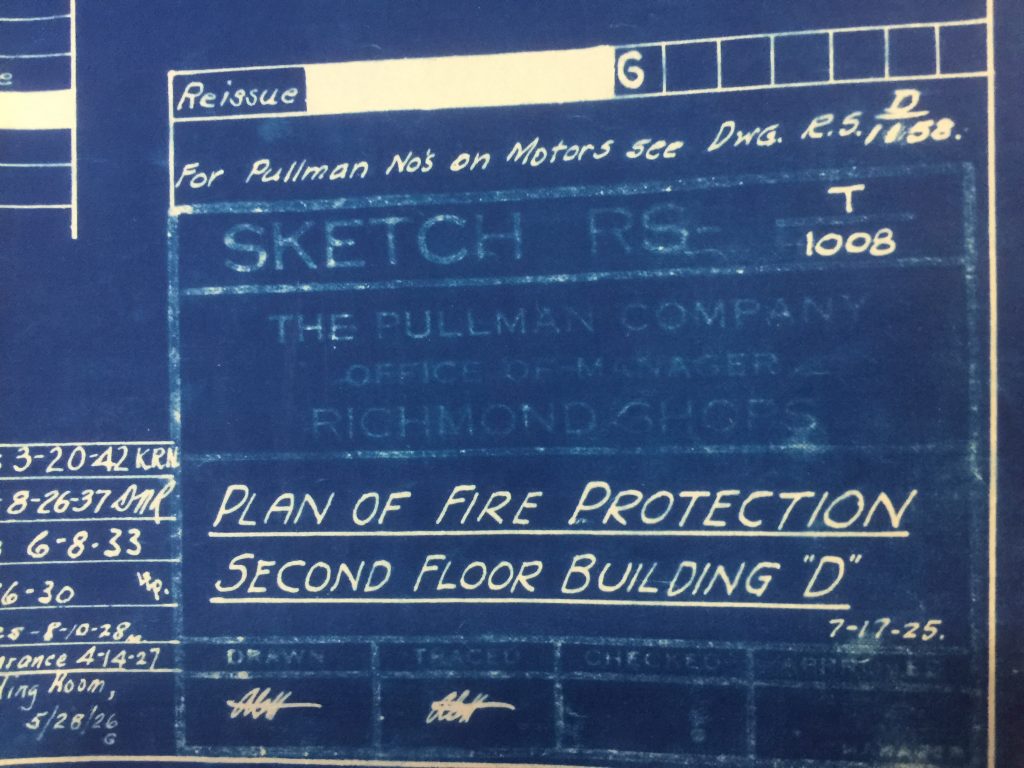

Pullman’s project set the world buzzing with interest. The print media of Chicago printed updates on construction and witness accounts were printed around the world. One of these articles appeared in the fifth issue of the inaugural volume of The Railway Age Monthly and Railway Service Magazine (Vol 1, No. 5. Chicago, May 1880). The RAMRSM claimed this article, “Proposed Car Shops of Pullman’s Palace Car Company,” was the first authorized public statement about the planned construction of the works. The magazine printed a large map, included below, and asserted that the shops would be the largest and most complete rail car erecting shops in the world. The essay reports that the layout of the works will be “compactly located as regards each other” providing for the efficient movement of materials and people, will include “Only first class machinery,” and will be “provided with numerous turn tables so that cars can be run in and out without switches.”

Of particular interest is this sentence: “The plans of these great works have now been fully elaborated, down to the location of every piece of machinery, and work will be commenced as soon as the final selection of location [is complete]” (p. 269).

The suggestion of very detailed and thoughtful planning in factory design is reflected elsewhere. Bessie Pierce translated the report of French economist de Roussiers about the works (1933, quoted in Buder 1967:58):

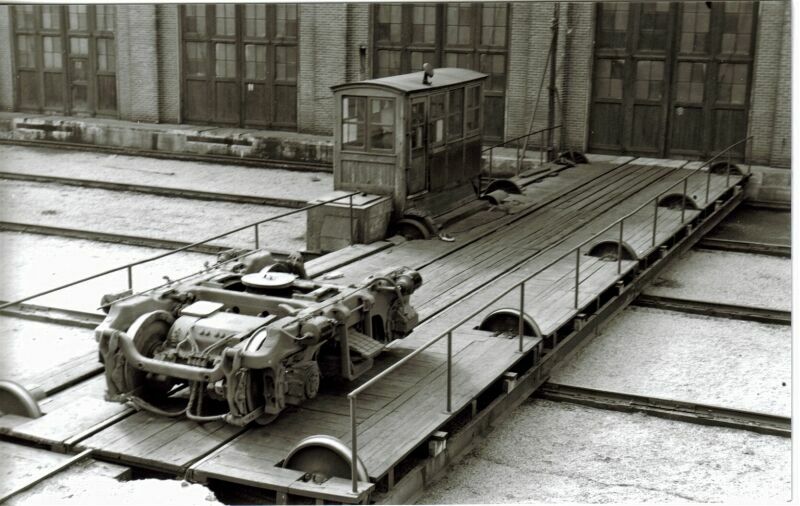

The planning of these workshops is remarkable, and every detail seems to have been considered. To cite one point, the buildings in which the freight-cars are built are a series of vast sheds as broad as the cars are long. Opposite each car a large bay opens on the iron way and a car, as soon as it is finished, runs along the rails and leaves the shop. All the timber that forms a car is cut to the required size and is got ready for fitting together in a special department, whence it is brought along the same rails to the sheds where the car is built. Tiny little locomotives are running along the lines which are built in the spaces between the various workshops…. Everything is done in order and with precision; one that no blow of a hammer, no turn of a wheel is made without cause. One feels that some brain of superior intelligence, backed by a long technical experience, has thought out every possible detail.”

Buder noted that Beman invested great care in planning movement and flow of materials and personnel, installing more than 20 miles of track through the facility. He used bridges to connect the second and third stories of nearby buildings so workers would not have to descend, cross a light railway, and the climb up again to complete a task.

So, again, how did Solon come to this design? We want to know this because it provides a starting point from which we can interrogate the material evidence about life-history of the Pullman factory: as-designed, as-built, as-lived and as-used, then redesigned, used, redesigned, used, redesigned, and so forth until abandonment and demolition.

It is safe to say that in 1878, Solon Bemen knew nothing about rail car manufacture or erecting shops. He must have spent a great deal of time with George Pullman and other company staff talking about production. Stan Buder explained that Bemen visited Pullman’s Detroit yard in mid-November of 1879. He then left for New York and visited a series of car shops along the way during the trip. We still need to research the archival material left by Bemen and see what we can learn about these trips.

This map that accompanied the RAMRSM article is really interesting and a bit mysterious. It is a measured plan of the buildings, showing their arrangement. Presumably Pullman’s staff sent this drawing to the magazine. This is the first graphic representation of the Pullman factory that we’ve been able to find.

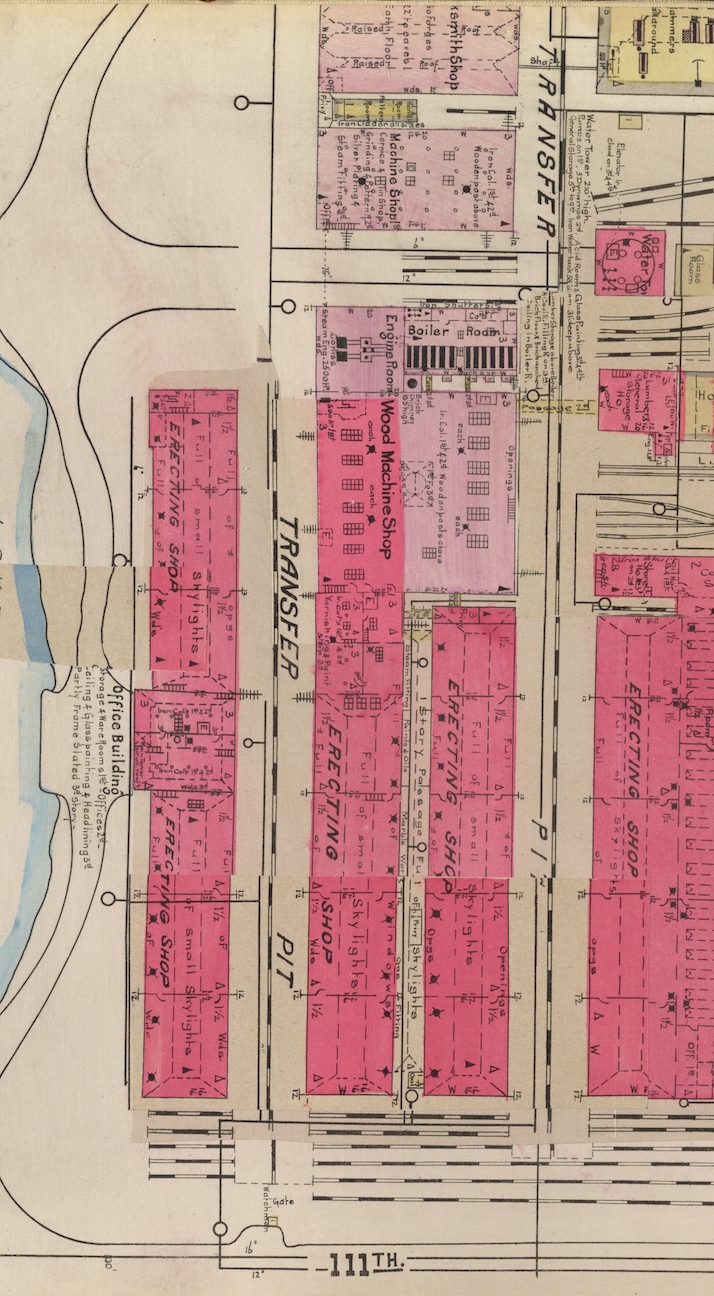

Readers can compare this with the map below, which represents “as-built” and then “as-lived” for the employees working during Pullman’s first decade in operation in Chicago.

The comparison is really interesting, since the layout of buildings in the 1880 plans is similar to what was actually built. Had Bemen worked out the process flow through the factory already by the time they released this map to the magazine? When did George Pullman select the final site for the factory on the land acquired by the Pullman Land Company? When did Bemen make the final adjustments to the design for layout?

If we can find the production records, we hope to be able to answer many of these questions!

Our first formal site visit as a team took place last week during our spring break. A number of us went down to make some connections at the

Our first formal site visit as a team took place last week during our spring break. A number of us went down to make some connections at the