Fort Michilimackinac played a pivotal role in the Northwestern fur trading industry from its founding in 1715, up to its abandonment in 1783 . Originally built by the French, Fort Michilimackinac originally came to be as a supply depot for fur traders in the Upper Great Lakes region as a means to export furs through the St. Lawrence Seaway and back to Europe. Although the Fort was built in 1715 by the French, the French presence in the region had existed since as early as 1678 (Ross, pg. 276). Over the next 8 decades ownership of Fort Michilimackinac would change hands between the French, the British, and the native Indians in the region before being abandoned.

Early French Influence in the Great Lakes Region

The French came to the Straits of Mackinac in the early 1600s and became well established later into the mid 1650s as a central location between Lake Michigan and Lake Huron to regulate water traffic. The fur trade was exploding during the mid-1650s into the 1700s when Fort Michilimackinac was established. The Straits of Mackinac provided a strategic point economically and militaristically for the French fur trading operations(Miller, pg. 7). The French saw potential markets in a variety of furs such as mink, ermine, fox, marten, otter, and most importantly beaver. The beaver fur was the most lucrative because beaver fur hats were popular in the colonial Europe during this time period. Fur traders made their best profits trading these beaver furs. A relationship between the French and the Indians was soon built, as the Europeans could offer goods of a modernized society to Indians in return for furs. Some of the most desired goods by the Indians included knives, cloth, guns and ammunition(Kalman, pg. 24).

As the fur trade exploded, the demand for furs by the French became greater and greater, and caused tension between the French and the native tribes in the area. The French began to claim land in the Straits of Mackinac. The French claim to native lands caused a displacement of Indians to other areas. This caused tension between native nations as well as the French. At this same time period, British trade influence was being established further east as Hudson’s Bay Trading Company was established in 1670. A lot of smaller companies around the James Bay area became united under this Hudson’s Bay Trading Company Entity, and as a result created direct market competition to the French fur trade industry already established in the Straits Of Mackinac and Westward into the Lake Superior and Green Bay area. It was around this same time period when father Jacques Marquette established a mission on the north side of the Straits Of Mackinac which is present day St. Ignace (Miller, pg. 8). This clash between British and French fur trading markets caused the French to have to change the way they went about establishing trade relationships with the Indians. They soon established many other trading posts along Lake Superior Region.

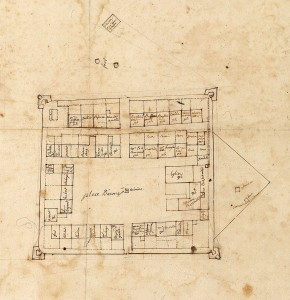

By the turn of the century the French began so see the value of holding the Straits of Mackinac with military power and sent a French Army to garrison to the Mackinac area to try to get the local natives to form an alliance with them against the Fox and Iroquois Indians. Their reasoning for this was that the Iroquois were the main trade partners of the British, and were seen as direct market competition to the French fur trading efforts. The Fox Indians were nuisance of sorts, as they kept stirring up tension between the local Indians the French traded with at Mackinac and it was disrupting their trade volume(Miller,pg. 11). After French occupation of the Straits of Mackinac for several years at the turn of the century, Fort Michilimackinac was established in 1715. A map of the early design of Fort Michilimackinac by Michel Chartier de Lotbiniere is shown in figure 1. This is the earliest known map of the fort. De Lotbiniere was a French military engineer for the regiment stationed at Fort Michilimackinac during this time period. This map was created in 1749.

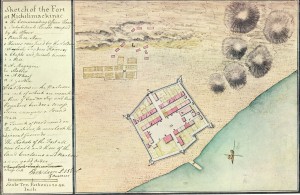

When the Fort was first built, you can see from figure 1 that the Fort is not immensely large, and is poorly scaled based on the drawing. However, the map does show the names of the people who lived in the fort during this time, as well as the number of people living there during the 1740s. Some 40 homes existed in the fort during this time period. Numerous additions were made to the fort. The first major addition took place during the 1730s and the 1740s, which allowed the fort to create a new identity for itself that was something more than just a little trade post in the north woods. There were a number of row houses that were divided into smaller structures for people to live in, and it created the living quarters for the 40 homes comprised within the fort. This created the living situation that can be seen in figure 1 and 2. Figure 2 is another drawing of Fort Michilimackinac by Lt. Perkins Magna of the British 17th regiment(Moreau,pg. 28).

This map highlights more accurately individual living quarters which can be seen as they are sectioned off into squares. This map was drawn post French and Indian War, so at this point in time there were French and British people living within the walls of Fort Michilimackinac. These demographics were predominantly segregated, as you can see by the labels in figure 2.It is important to note that while the French garrison was stationed in Fort Michilimackinac they weren’t involved in hardly any military operations. Their main purpose was to protect the hundreds of trader coming in and out of the trade post on a daily basis. The French and Indian War was a direct result of competition in the trade market that both European countries had tapped into. Now due to British expansion in the 13 colonies, they had a numerical advantage when it came to pushing their agenda on the French. The French were scattered on territory from Lousiana all the way up to Canada through the Great Lakes.

The French remained in control of the Fort Michilimackinac until the end of the French and Indian War, at which time the Fort was turned over to the British in 1761. This was a time at which the Indians of the Great Lakes Region sided with the French, as the French were greatly outnumbered in comparison to the British colonies on the Atlantic Coast. Fort Michilimackinac served as a gathering location for all local native tribes when drawing alliances for the French and Indian war in 1753. All local native nations decided to side with the French. The French were defeated regardless of the alliance formed between the French and Indians in 1753. The British were much less cooperative with the natives during beginning of their control of Fort Michilimackinac, which eventually lead to Pontiac’s Rebellion in 1763, immediately after the French and Indian War officially concluded[7].

The British Era

The British took hold of Fort Michilimackinac immediately after the French and Indian War, but then were attacked in an event known as Pontiac’s Rebellion.Pontiac’s Rebellion was a direct result of the native Ojibwa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi natives unhappiness with post French and Indian War negotiations. Fort Michilimackinac saw direct consequences of Pontiac’s War when local Indians staged a game of lacrosse outside the walls of Fort Michlimackinac. The ball was launched inside the walls of Fort Michilimackinac as an excuse for entry, where the British residents inside the fort were slaughtered. The local natives remained in control of the fort for an entire year before the British were able to regain control of the fort through peace negotiations. Similar stories of the slaughtering of local fur traders in the Upper Great Lakes area would become commonplace over the next 10 years following until order was restored due to the fact that local natives had become dependent on British trade as a means of livelihood. They relied on European weaponry, and clothing as a way of life(Jackson, pg. 255).

The British returned to Fort Michilimackinac and took the fort back a year after it had been sieged by the local indians. At this point they started immense reconstruction of Fort Michilimackinac. The row houses that were seen in figures 1 and 2 ended up being used for military purposes now instead of civilian housing under the French. Some of the housing in the Fort was rebuilt as well[5]. There was an interesting dynamic to the society within the walls of Fort Michilimackinac, as British and French people both resided within, as some of the French didn’t move down to their other settlements in Illinois. This quickly created a division between the occupants of the fort. During the British Era of fort occupancy, there was a gradual population increase and most of the French were eventually forced into living in a small village just outside of the walls of the fort.

While fur trade flourished under British command, so did the corn trade. The British found that the area southwest of Fort Michlimackinac grew corn very well. When it came to fur trade, the British system was very different from the French. The British trade network consisted of Kings Posts and Free Posts. Fort Michilimackinac was a Free Post, meaning that any person could trade as they purchased a permit from the king’s agent. This created a free market system in which the cost of goods was governed by free trade. The British didn’t like the French system because it allowed monopolies to be formed if they wanted to buy a permit. Monopolies resulted in a higher price when it came to negotiating with the natives [1]. The British remained in Fort Michilimackinac until the arrival of Captain Beamsley Glazier. In 1770 he wrote a letter to General Cage of the British regiment that talked about what living conditions were like within the walls of Fort Michilimackinac. He said that “As this Fort stands in so bad a place the landing is so difficult, large hills and deep gullies, which are within 40 yards of the west and south Bastions and spread themselves a Quarter of a mile in circumference, where 1500 Indians may ly under cover from any fire from the Fort excepting Shells, and the Repairations this Fort will want in a little time; If I may be allowed to give my opinion it would be but little more expences to build a Small Fort about ¾ of a mile from this, round the point to the Eastward where this is a good Cove for Landing and a high spot of ground very convenient; but the best place would be the island called Michilimackinac about 8 Miles North from this Fort where there is good landing and wood plenty, which in little time will be very difficult to be got here as we are not obliged to go 7 or 8 Mile for it and it is a great distance from the Shore there”[6]. This initiated the move to Mackinac Island, where the present fort stills stands. The materials that could be used from Fort Michilimackinac were moved to Mackinac Island and the rest of the material that wasn’t used was burned to the ground. It wouldn’t be until the 1960’s that excavation of the fort would take place and the discovery of the layout of the fort would allow historians to piece together the structure of Fort Michilimackinac.

Restoration

Eventually in the 1880s railway was constructed leading up to what is now known as Mackinac City. This resulted in the establishment of Mackinac City. It wouldn’t be until the 1960s that the remains of Fort Michilimackinac would be unearthed and restored. It is now a National Historical Landmark open to the public.

Secondary Sources

1) Jackson, M. (1930). The Beginning of British Trade at Michilimackinac. Minnesota History, 11(3), 231-270.

2) Thwaites, R. G. “AN OUTLINE OF MACKINAC HISTORY.” Bulletin of the American Library Association4,no. 3 (1910): 522-24.

3) Ross, Frank E. “The Fur Trade of the Western Great Lakes Region.” Minnesota History 19.3 (1938): 271-307. Web.

4) Pratt, Julius W. “Fur Trade Strategy and the American Left Flank in the War of 1812.” The American Historical Review 40.2 (1935): 246-73. Web.

5) Moreau, Maxwell S. Excavation at Fort Michilimackinac : Mackinac City, Michigan, 1959 Season / by Moreau S. Maxwell and Lewis H. Binford. Lansing: Michigan State U, 1961. Print.

Primary Sources

6) Glazier, Beamsley. “Captain Glaziers Letter.” Letter to General Cage. June 1769. MS. Fort Michilimackinac, MI.

7) 15,2015 Posted May. “The Four Maps of Michilimackinac.” Mackinac State Historic Parks. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Nov. 2016.

8) Miller, J. J., II. (1970). Eighteenth-Century Ceramics From Fort Michilimackinac, A Study In Historical Archaeology. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Further Reading