The Haymarket Affair was a clash between civilian and police that resulted in a bombing that took the lives of multiple officers and citizens, soldier and police search and seizures of homes for weeks after the event (red scare), and a lasting movement for labor and work time reformation nationally.

Background Information

Labor movements and protesting had been going on for a number of years up until the bombing in Haymarket Square. These movements spurred mainly following the Civil War during America’s first Great Depression, the Long Depression of 1873, also known as the Panic of 1873. During this time, America’s biggest industries, railroads and steel/iron production, saw a drastic decline in production. In Chicago, the Long Depression of 1873 hit especially hard as this was a sucker punch following the Great Fire of Chicago in 1871. This event left well over one hundred thousand residents homeless, including many immigrants, and took a financial and mental toll on the city. Between these two devastating tragedies, the system for maintaining current and producing new jobs crumbled, putting hundreds of thousands of laborers out of work. Throughout the mid-1800s to the time of the fire and depression, German immigrants showed a large boom in immigration numbers, particularly in Chicago where they would work little over ten-hour workdays, for six days a week. As workers began to demand better working conditions and pay from their employers, said employers would undermine their efforts through various methods. Such methods included disallowing known union sympathizers from coming into work, firing workers, hiring “strikebreakers,” workers who would not strike, but simply work, or even employing people specifically meant to disband or discourage demonstrations and protests. In the book by Henry David, he goes on to talk in quite a length about the methods employers would enforce against union sympathizers, including a blacklist, which “was the employers’ method of boycotting obnoxious workers. Names on the list were circularized among employers within the same trade, and workers thus distinguished found it impossible to secure employment within a given district or even in other regions,” (David 23-24). With tensions rising between bosses and their employees, the only logical solution was for the police forces to begin getting involved as violence became more and more common as a tactic between anti-union versus pro-union movements.

Initially, the conflict right before the bombing was solely between police and socialists who were peacefully protesting multiple problems common among citizens/unions. After the bombing from anarchists took place, federal and state involvement became more apparent as the event led to a “red scare” particularly of Germans in the community. Soldiers and police worked together through funding from the community and businesses to conduct an investigation of suspects directly tied to the Haymarket incident.

The incident took place in the heart of Chicago, in Haymarket Square. Originally protests took place at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company when protesters were planning on confronting McCormick strikebreakers and also protest in favor of an eight hour work day, but then evolved into protests against police brutality due to a fatality that occurred during prior mentioned protests at the McCormick Harvesting plant when police forces open fired on a group of strikers approaching aforementioned strikebreakers.

The event in which the bombing took place specifically happened on May 4th, 1886. Subsequently, ransacks and searches for the following eight weeks led by the Chicago police force, and aided by soldiers. From June of 1886 to August of the same year, the trial of eight anarchists suspected of being in cahoots with the bombing that took place in early May of that year.

The Tragedy and its Outcome

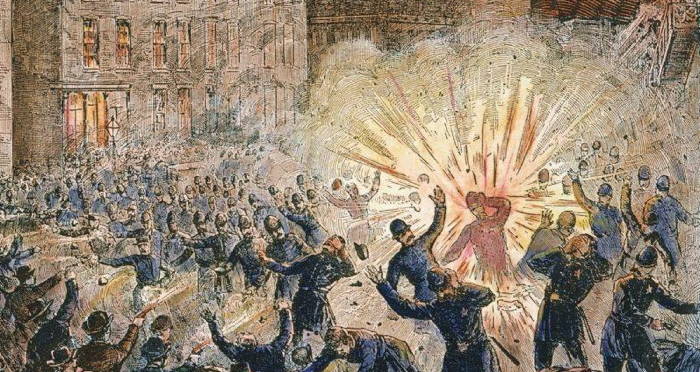

As stated before, the event was a bombing that led to rioting and mass hysteria and chaos on May 4th 1886 in Haymarket Square in Chicago Illinois. It was a peaceful protest demonstrating against police brutality that was result of a fatality days before in front of the McCormick Harvesting plant. The protest had multiple socialists speakers speak before hundreds of citizens and union enthusiasts. In the midst of the protest, police became involved as they tried to disperse the protesters, in which triggered anarchists in the crowd to throw a dynamite bomb. David writes, “Abruptly, and with no other warning than the dimly glowing light and slight sputtering of its fuse, a dynamite bomb hurtled through the air. It struck the ground, and with a fearful detonation exploded near the first rank of police” (David 204). Immediately after the bomb was thrown, police forces came to their senses and began open firing on the civilians and spectators in the crowd. The event swiftly found its end as “people fell right and left, struck by bullets or clubbed down… the meeting place was clear, and but for their moans and cries, quiet,” (David 204). Following the incident, the community reaction was more in favor of anti-union, and police support as homes, meeting places, and places of business were constantly searched by police in search of clues/suspects involved in the tragedy at Haymarket Square. After several months of arrests and trials, eight men were convicted of the bombing that took place that day. These men were well known radical leaders at the time, including August Spies, a labor activist who also edited a newspaper in Chicago. Ironically enough among the defendants, “three had never even set foot in Haymarket Square on that even of May 4, 1886. Three others left the rally before the explosion took place, and the remaining two were on the speakers’ platform and thus nowhere near the point were the bomb was thrown” (Chicago Tribune 1984). Since this information was not known at the time, nor was it known until years after, seven of the accused were sentenced to death by hanging while the remaining defendant was sentenced to a whopping fifty years in prison. After a series of appeals, another prisoner was sentenced to life in prison rather than by hanging. On the day of the executions, one of the prisoners committed suicide by sticking a bomb in his mouth where it blew his head off, and the other four remaining prisoners were killed by hanging in the gallows on November 11th, 1887.

Lasting Effects

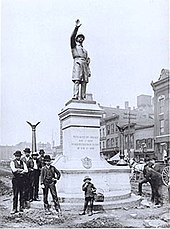

Overall, the lasting effect the Haymarket Riot had was a massive dent in the labor union’s efforts and public opinion. This is particularly true with one of the biggest labor unions at the time, the Knights of Labor. They were a more radical group of unionists who especially after the Haymarket bombings, were accredited with being mainly anarchists. They also lost favor as another labor union came into fruition, the American Federation of Labor, who took many if not all of the Knights of Labor’s followers. Another lasting effect was a profound feeling of xenophobia, basically an irrational fear of foreigners, from the public. Since Germans were linked to the bombing, as a group they were the target of prejudice from the public. Not only was their public backlash, but police forces started to retaliate as well. Police brutality was a newly coined term of this time and was used alongside the backlash against the German community of Chicago. Police and anarchist’s bad relationship did not end there, as the statue erected in honor of the seven policemen who died during the bombing has served as the host for a handful of acts of vandalism committed by anarchists. A Chicago Tribune article from one of said vandalism acts reads, “The monument has had a history almost as story as the rioting it commemorates. Since it was erected in 1887, it has been moved three times, almost moved two other times, was wrecked when a street car crashed into it in 1927, was defaced by vandals, and has been sandblasted and restored,” (Chicago Tribune 1969). This newspaper was written when the first of two bombings in 1969 and 1970, respectively, took place at the site of the statue in an effort to destroy it. The statue today stands at the Chicago Police Headquarters and has not received the same treatment as it had in the past.

Along with the lasting bad relationship between anarchists and police force, and an outbreak in xenophobia, the Haymarket Square still came to serve as a center for protests, and reminders. This can be attributed partially to the lasting memory of those that were hung in 1887. For example, Albert Parsons, one of those convicted, was quoted saying “We are revolutionists, we fight for the destruction of the system of wage-slavery,” (Chicago Tribune 1984), and August Spies is famously known for calling out, before being executed, “The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strange today,” (Chicago Tribune 1984). Both these quotes truly show how die hard these anarchists were in their conquest to achieve fair labor laws and dispel police brutality; so much so that they faced the gallows and still had the will to cast out against the status quo. An excerpt from Henry Demarest Lloyd’s, an american journalist at the time, journal exemplifies how much of an effect these men had on the working class and their stance on work reformation. After the executions he writes that the men “have died in vain, unless out of their death come a resurrection and a new life… They have been killed because property, authority, and public believed that they came to bring not reform but revolution, not peace but a sword,” (David 533). Nearly eleven years later, another protest was held in the square for more labor disputes. An anarchists who was around for the Haymarket bombing was quoted saying, “The men who are behind the movement were formerly connected with the local organization of the International Labor association, which was prominent in the labor troubles which led up to the Haymarket riot,”(Chicago Tribune 1897), and also noted that “the place was chosen because of its historic associations,” (Chicago Tribune 1897). Despite the tragedy of the bombings, and the backlash the labor movements received, they still harnessed the location for meetings and historical importance when protesting.

Primary Sources

- Grossman, Ron. “Defusing the Mysteries of the Haymarket Bombing: The Haymarket Tragedy Haymarket Riot.” Chicago Tribune (1963-1996) Jul 29 1984: 2. ProQuest. 15 Nov. 2019 .

- “Haymarket Statue Bombed.” Chicago Tribune (1963-1996) Oct 07 1969: 1. ProQuest. 15 Nov. 2019 .

- “The Haymarket Affair.: Today the First Anniversary of the bloody occurrence. Fatally Injured–7…” Chicago Daily Tribune (1872-1922) May 04 1887: 3. ProQuest. 15 Nov. 2019 .

- Kelley, John. “Retell Haymarket Riot.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923-1963) May 05 1925: 8. ProQuest. 15 Nov. 2019 .

- “Meet in the Haymarket: Anarchists call an open-air session for Sunday morning… ” Chicago Daily Tribune (1872-1922) Jul 10 1897: 1. ProQuest. 15 Nov. 2019 .

Secondary Sources

- Lembcke, J., & Howe, C. (1987). Chicago Haymarket Centennial. International Labor and Working-Class History, (31), 96-98.

- Hild, Matthew. “The Knights of Labor and the Third-Party Movement in Texas, 1886–1896.” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 119.1 (2015): 24–43.

- David, Henry. The History of the Haymarket Affair : a Study in the American Social-Revolutionary and Labor Movements. [2d ed.]. New York: Russell & Russell, 1958.