Fort Michilimackinac is located at the northern tip of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula. The Fort is easily seen from either side of the Mackinac Bridge, connecting Michigan’s Lower and Upper Peninsulas. The Fort served as a trading post with access to the St. Lawrence River which empties to the Atlantic Ocean and the Upper Great Lakes. In the area, fur was the main trade. It was constructed by the French in 1715 and later abandoned in 1783. In 1761, the French garrison left the Mackinac Straits after the French and Indian War subsided and British troops arrived. The French had encouraged the Ojibwe Tribe to get rid of the English. On June 2nd in 1763 the Native Americans played a game of baaga’adowe (similar to modern day lacrosse) and the British watched as they often did. However the game was staged to divert attention from the attack the fort in what is now known as the Massacre of Michilimackinac. This was part of a Native American movement called Pontiac’s Rebellion where Native Americans raised up against British troops in many forts in the Upper Great Lakes Region.

Causes of Pontiac’s Rebellion

Before the War of 1812 Native Americans tribes of Ojibwe, Wyandot, Huron, Potawami, and Ottawa in the Upper Great Lakes area had, an excellent relationship with the French that were in their territories. After the War of 1812 the British took over the Forts that were near the tribe’s home territories and began encroaching on them. The Natives did not like their new neighbors as the French were very kind to them, giving them gifts and did not heavily colonizing in their lands. This relationship was developed over many years and fighting as allies with the French in the French and Indian War. The British, in native eyes, were extremely untrustworthy. They also began colonizing their lands and not giving any sort of compensation for it. British settlers treated the Natives as inferior to themselves. For those reasons, a coalition of Ojibwe, Ottawa, Wyandot, and Potawatomi agreed to attack the Forts nearest their settlements. The individual tribes of Native Americans agreed to come together to attack the Forts that were close to their home territory.

Pontiac’s Rebellion was a series of attacks on the British throughout Michigan, Ohio and Illinois. The attacks were brutal, with the killing of many civilians and prisoners. The natives were ruthless in their attacks which stemmed from years of British rule in their respective areas. Not even women and children were spared during most attacks, many were scalped either before or after death, even stories of the Natives cannibalising a British man as part of their war ritual[6]. The British, after the French and Indian War, took over forts in the Great Lakes Region. One of which was Fort Michilimackinac. This fort would eventually be the fifth target of what became known as Pontiac’s Rebellion. This became known as Pontiac’s Rebellion after the Chief of the Ottawa. He is thought to be the mastermind behind getting the different Native American tribes to come together. He was one of the reasons that the French and the Natives had an alliance [3].

Fort Michilimackinac Attack

This attack was quite clever in it’s design and was how many of the smaller Forts were taken. The Tribe would formulate some reason to get inside the walls of the Fort and smuggle in their weapons and catch the British soldiers and settlers by surprise. The Natives at Michilimackinac began playing what we would compare to lacrosse. Many times the soldiers of the Fort would watch [7]. The Natives asked the British soldiers if they would like to watch as the Ojibwe were to take on the Sauks. They were said to have mentioned the game was in honor of the British King George III. As described by Alexander Henry, the Natives began the game, while he was not at the game or the Fort, he was outside preparing a canoe to go to Montreal. He heard the battle cries begin and went outside to witness what he described as “I saw several of my countrymen fall, and more than one struggling between the knees of an Indian who, holding him in this manner, scalped him while yet living [1].” Henry states that the French Canadians of the fort were left unharmed and did nothing to try to stop the Native invasion. Henry managed to escape the ordeal by hiding in the basement of one of the French Canadians houses outside of the fort. This was actually very uncommon, most of the French Canadians did nothing to help any of the British settlers. Even the house where Henry took refuge in turned him away when he was looking for a place to hide out. In fact, the owner of the house did not invite him in. While Henry was seeking help, he ended up sneaking in with the assistance of the man’s slave. The attack took many lives of the British soldiers and British settlers [1]. The lack of French Canadian help during all of the different attacks on Forts was reported. They did not help the Natives attack or the British seeking refuge and were spared by the tribes that were raiding the Fort. As mentioned before the French and the Natives had a very strong relationship. Which was shown during the sieges on the various forts.

As terrible as this attack was, there were warning signs that were ignored in the days and weeks leading up to June 4th attack. There were many fur traders that had warned Major George Etherington (the British commanding officer of the fort) of the increasing Native American activity in the area to which he ignored. Etherington became so annoyed with these warnings he threatened to have the next person who spoke of this to be sent to Fort Detroit and imprisoned [6]. Had he taken these warnings seriously this attacked most likely would not have been avoided but more casualties would have ensued. The fort was well armed and with taking the warning seriously the British garrison would have been prepared and could have prepared to defend themselves. Etherington would not have been caught off guard however A British victory would have been very difficult as they only had around 50 men and the Native Americans were said to have somewhere between 400 and 500. The attack would have cost the lives of many more Natives as they were armed with Tomahawks, which could not compete with the British muskets of the time. All in all the warning of the imminent attack may have helped the British defend themselves better, the outcome would have remained the same. With the superiority of the British weapons they would have inflicted more casualties to the Natives, but they were so grossly outnumbered that eventually they would have ran out of ammunition and been overrun by the Natives.

This attack, which was fifth in the string of attacks, became known as Pontiac’s Rebellion. This attack was very successful as the British did not send reinforcement to the Fort. It took the British a year to reclaim the Fort. The British would retake the Fort peacefully, offering gifts to the Ojibwe and agreed to treat them more like the French did before the Rebellion. Meaning that the British would not send as many settlers to their lands and they would do more trade with them.

Pontiac’s Rebellion Outcome

Although it was Pontiac who eventually surrendered in 1766 and the British won on paper, they did not defeat the Natives, as one would have thought. The Rebellion was very successful at first. The Natives took many of the smaller Forts such as Michilimackinac and, although not taking over Fort Detroit, won many of the battles while surrounding it. The British did not necessarily beat them in many battles, they instead sought a political end to the rebellion. Pontiac eventually gave in to their peace offer as he was having trouble finding warriors due to disease that had hit the Natives hard during this time. Knowing that eventually the British would defeat them they agreed to the peace terms. So the Native Americans did part of what they set out to do. Though, they did not completely drive out the British they achieved gaining respect from them [5].

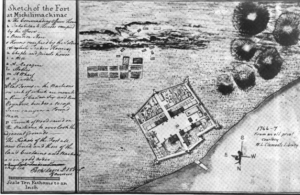

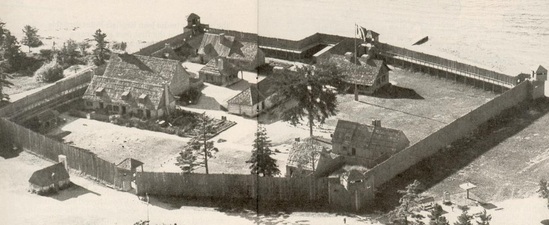

At Michilimackinac the British regained control of the Fort about a year after the massacre. However, in 1783 the British realized the Fort was a tactical nightmare to defend (as you can see below in the sketch of the Fort just after it was completed.) You can see that it was right next to Lake Michigan and although it was a great trading post, the Fort walls were made of wood and it was not strategically placed or properly built for defensive purposes. The Fort was at sea level giving it no credible advantage and making the Fort useless [2]. With the Fort being at sea level does not give it any sight advantage to prepare for any enemy ships on the way. This also gives them a disadvantage from a land attack the inhabitants are are basically sitting ducks. Because of this, the British came to the realization that they needed to move so they relocated to Mackinac Island and made a much more reliable and defendable Fort. This included better walls that were constructed out of limestone. This island fort, they believed, would be easier to defend than Michilimackinac. In 1960, the fort was declared a National Historic Landmark and is now a popular tourist attraction. People come from all over the country to witness the reenactments from the War and how life was, in general, living in Fort Michilimackinac in the 18th century. Fort Michilimackinac is one of the most extensively excavated early colonial French archaeological sites in the United States [4].

Primary Sources

- Emery, B. F., Michigan Mutual Liability Co., Detroit., & Old Forts and Historical Memorial Association (Detroit, Mich.). (1931). Fort Michilimackinac, 1715-1780: The scene of the Pontiac massacre, June 4, 1763. Detroit, Mich.

- Henry, A. (1971). Attack at Michilimackinac: Alexander Henry’s Travels and adventures in Canada and the Indian territories between the years 1760 and 1764. Mackinac Island, Mich.: Mackinac Island State Park Commission.

- Peckham, H. H. (1947). Pontiac and the Indian uprising. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Secondary Sources

- Widdler R. Keith. “After the Conquest: Michilimackinac, a Borderland in Transition, 1760-1763” (Central Michigan University – Mount Pleasant, MI, 2008

- Petersen, Eugene T. “Michilimackinac: it’s History and Restoration.” Mackinac Division Press, 1962

- Middleton,Richard. “Pontiac’s War: Its Causes, Course, and Consequences” (Central Michigan University – Mount Pleasant, MI, 2009)

- Edwards, Lissa. “Deadly Lacrosse Game in Mackinac Straits at Fort Michilinmackinac in 1763.” (Prism Publications – Traverse City, MI, 2010)