At the end of World War II, Fort Snelling was the home for the Military Intelligence Service School (MISLS). The students were Japanese Americans also called Nisei, who became the translators for the Pacific theatre. Fort Snelling was also the birthplace of new, specialized railway military units to work along with civilians in each major railway company. Alongside the railway units, Fort Snelling also trained military police units to protect facilities and transporting prisoners of war.

Brief History of Fort Snelling

Fort Snelling was the first major frontier military fort in the northwest region, located at the convergence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers. During its construction from 1820 to 1824 it was originally known as Fort Saint Anthony. However, after its completion it was renamed Fort Snelling in honor of its commander and architect, Colonel Josiah Snelling. The fort was constructed to stamp out British influence in the northwest after the War of 1812.

After Fort Snelling was completed, its primary duty was to protect booming U.S fur trade interests in the region. The fort was also responsible for keeping peace in the region through deterring advance by the British in Canada, and to prevent the encroachment of American settlers by enforcing boundaries of the region’s American Indian nations. Fort Snelling also attempted to keep the peace between the Ojibwe and Sioux people. However, during the early 19th century the Northwest Territory was relatively peaceful. Because of this the fort’s garrison would spend its time farming 400 acres of crops, and cutting wood to keep them warm for the long winters.

For nearly 40 years fort Snelling remained in service until in 1858 Minnesota became the 32nd state. By that time the towns of Minneapolis and St Paul became more developed and increased in population. Also the United stated had more forts in the region that were further to the west, causing fort Snelling to no longer be needed. After this the old fort was purchased by a local entrepreneur Franklin Steele, who was also a former Fort Snelling sutler. Franklin intended to sell off sections of the fort for a new city called “Fort Snelling”.

Fort Snelling was used many times after it was sold by the government. During the Civil War, Steele leased the fort back to the U.S. War Department for the use as an induction station. During this time more than 24,000 Minnesota recruits were trained there. During the Dakota War of 1862, Fort Snelling was used again as a concentration camp. It held hundreds of Dakota women, elders, and children as captors on the river flats below. After the war Steele began leasing the lands around Snelling to settlers and the United States Army stationed a garrison at Fort Snelling to protect settlers from the Dakota people. Fort Snelling soldiers also fought in the Indian Wars and the Spanish American War of 1898. During World War II, The fort was used as the location for the Military Intelligence Service Language School to teach Japanese to army personnel.

On October 14th 1946 Fort Snelling was finally decommissioned. After this the majority of the structures fell into disrepair. However, in 1960 it was listed as a National Historic Landmark, citing its importance for the regions history. Fort Snelling nevertheless continued serving as the headquarters as the U.S. Army Reserve 205th Infantry Brigade. However this also ended in 1994 because of force-structure eliminations. The fort was then reconstructed as an educational establishment, rebuilt to resemble its original appearance.

Fort Snelling in WWII

Fort Snelling was the main recruitment center in Minnesota during World War II. The Fort processed all of the men and women from Minnesota that joined the armed forces with its peak processing of 100 recruits a day in 1942. The new recruits went through the standard recruitment process of physical examinations and intelligence tests. The results of the test would decide the fate of the recruit. High scores were mostly assigned to the Air Corps, while low results usually meant they were assigned into existing units as casualty replacements. However, when Fort Snelling reached its peak of over 1,000 staff soldiers and civilians, difficulties arose. One of the main difficulties Fort Snelling had to face during the war was figuring out how to house and feed all of the recruits. Eventually the fort solved the problem by converting the post field house into an 850 bed dorm. It also drastically increased the speed at which it served meals to 3,200 soldiers in 75 minutes. The grounds of Fort Snelling contained a barracks that were on the lower post for recruits in training. Another barracks was on the upper post along with the headquarters with its clock tower and antique cannons in the yard. Fort Snelling was also directly connected to the railroad lines, where it received tons of supplies, food and clothing every week. One of the most intriguing units to go through Fort Snelling was the 99th infantry. They were required to have experience with snowshoeing, skiing, and to be conversant in Norwegian In order to invade Norway. However, the plan never ended up happening. And the 99th infantry fought as line infantrymen across Europe instead.

As the United States came closer to joining World War II, military officers realized that there would be a need for Japanese translators. To accomplish this, a language school for military age Nisei “Japanese Americans” was created in San Francisco November 1, 1941. The school was mandated by the early discovery that most of the military age Japanese Americans had little knowledge of their native language. However, when President Roosevelt ordered the relocation of Japanese families, the school had to move or lose all of its students. Because of this, Governor Harold Stassen of Minnesota agreed to take in the school. The school moved to Camp Savage in the city of Savage MN, and was renamed the Military Intelligence Service School (MISLS). By 1944 the school had outgrown Camp Savage and was moved to Fort Snelling. The program included writing, reading and speaking Japanese; translation, interpretation, and interrogation; captured document analysis; Japanese geography and map reading; Japanese military and technical terms; radio monitoring; the political, social, economic, and cultural background of Japan; and studying the Order of Battle of the Japanese army. The graduates also served on the front line, broke codes, and became instructors themselves. Their service in World War II was such a great success that Major General Charles Willoughby said, “The Nisei shortened the Pacific theatre of World War II by two years and saved possibly a million American lives”. After the war in 1946 the language school was moved to Monterey California.

The Twin Cities’ economy was heavily dependent on the railways in the 1940s. Consequentially, Fort Snelling became the headquarters for the Military Railway Service in May 1941. The primary goal of the program was to oversee training of the Military railway solders (M.R.S.), and to maintain relations with the commercial railroads. M.R.S. did their technical training while on the job, learning how to lay track and repair engines. They also studied foreign railroad systems and their mapping. Early during the war, the M.R.S. saw the most action in North Africa. The battalions took over the captured railroads to supply the front lines and returned to rail supply afterwards. The M.R.S. was critical to the supply lines at home and at the front. They were responsible for getting the materials to the factories, and food or munitions to the front over captured rail lines. Fort Snelling also trained military police units designated as Zone of the Interior, whose function was to protect airports, munition plants, and supply trains. The units were also responsible for transporting prisoners of war and Japanese Americans to concentration camps.

Secondary Sources

- McNaughton, James. Nisei color guard: Nisei Linguists. Washington D.C.: Department of The Army, 2007. 301.

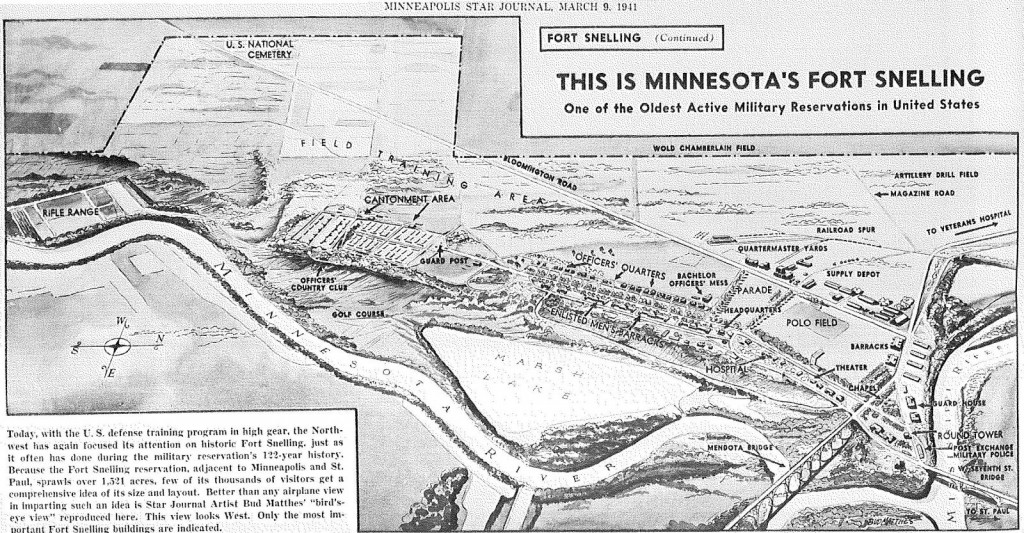

- Osman, Stephan. Drawing of Fort Snelling military complex. 2007. Minnesota Historical Society.

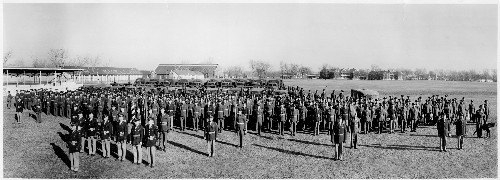

- Osman, Stephan. 710th military police battalion. 2007. Minnesota Historical Society.

- Hall, Steve. “The Expansionist Era.” Minnesota Historical Society. N.p., 1997

- Anderson, Dean L. A Carpenter Lock from Minnesota’s Historic Fort Snelling. Vol. 9. N.p.: Association for Preservation Technology International, 1977.

- Prucha, Paul F. The Settler and the Army in Frontier Minnesota. Vol. 29. N.p.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1948. 231-46.

- Hansen, Marcus L. Old Fort Snelling. Iowa City: The State Historical Society Of Iowa, 1918.