Red Wood Library

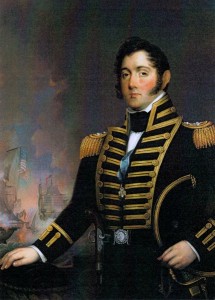

Oliver Hazard Perry was born August 23, 1785 to Sarah Wallace Alexander and United States Naval Captain Christopher Raymond Perry in South Kingstown, Rhode Island. Perry had three sisters and four brothers, one of which, Matthew Calbraith Perry, would also become a Commodore in the USN (United States Navy). Both sides of Perry’s family had a long line of Naval history, and from an early age Perry was immersed in a Naval lifestyle. His father had a large impact on his decision to join the Navy. His mother had a very spiritual type of influence on his life, and Perry was quite active in his Church. At 13 years old, Perry contracted as a Midshipman, one of the youngest people to ever do so. The average age of a Midshipman was 17 years old. He was assigned to the USS General Greene, a ship which his father was Captain of. His father mentored him while aboard the General Greene, molding him into a superb future Naval Officer. Perry’s early sailing experience took place in the Caribbean.

In 1800, the Quasi-War was causing problems for the USN. Perry was still aboard the USS General Greene when they had a skirmish with the French Navy near Haiti. Fortunately for the young Perry, this was the only conflict that he experienced during the Quasi-War. In 1806, he was given command of the USS Revenge, a sloop. This took place during the Embargo Act, which banned all exports from the US to Great Britain or France. This was done in order to maintain neutrality during the Napoleonic Wars. Perry’s duty was to patrol the Eastern Seaboard, making sure no ships snuck off to trade with European countries. According to a letter from the Oliver Hazard Perry Archives, Perry sent a request to the Secretary of the Navy, Paul Hamilton, to sail to Washington in order to make repairs to the Revenge on the 31st March, 1811. Ironically, in the winter of 1811, the Revenge crashed off the shore of Rhode Island. Perry was able to save all of his men, but he was still greatly distraught by the incident, even though it was determined to be the Pilots fault. He took a years leave from the Navy, marrying Elizabeth Mason and later having 4 children.

War of 1812

In 1812, the United States declared war against Great Britain, starting the War of 1812. During this time, Perry requested command of the Lake Erie Naval fleet. He was awarded Chief Naval Officer of the Lake Erie fleet. The fleet, to Perry’s disbelief, was almost non-existent. There was only one cannon, and a few half-finished ships. Perry arrived at Presque Isle, Pennsylvania, expecting to find a force of carpenters and guards that he had requested, ready to build the forts defenses and finish the ships. Of the 60 guards, most of them had fled. There were no carpenters. The town of Presque Isle was almost completely deserted. Perry tried again and again to gain supplies and men to build up the Lake Erie Naval fleet, but to no avail. He was finally able to convince a Naval agent in Pennsylvania to help him out, and he finally received enough men and supplies to start building his fleet.

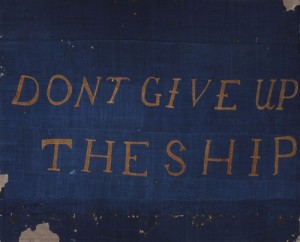

During this time, the British were encroaching on the Great Lakes, taking advantage of the poorly supplied fleets located throughout the Great Lakes region. In July of 1812, Perry found out that his close friend, Captain James Lawrence, had been killed in a battle near Boston. His dying words had been “Don’t give up the ship!”. This would become the unofficial motto of the modern day United States Navy. Perry named one of his newly constructed ships the USS Lawrence, and the other one was christened the Niagara. Perry also has “Do not give up the ship” embroidered on the sails of the ships. The one surviving flag from the Lawrence is on display today at the New York Historical Society. Perry now had the firepower and the ships to defend Lake Erie, but he did not have the men. Perry needed about 750 sailors, and he only had 120 at the time. Perry’s superior officer, Commodore Chauncey, failed him yet again. Chauncey never replied to Perry’s requests, greatly frustrating Perry. Near the end of the summer, Perry was able to scrounge up a motley crew of sailors, without help from Chauncey.

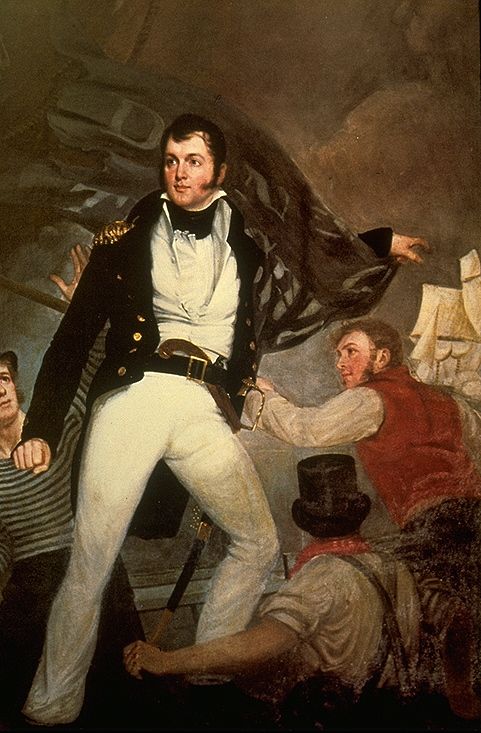

The Battle of Lake Erie

(from Maritime Quest)

The British on the other side of the Lake were not very concerned with the American forces

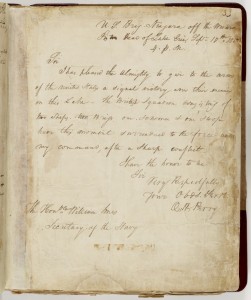

at this point. On September 10th, 1813, Captain Barclay decided to attend a dinner in his honor, leaving the British harbor exposed. Perry jumped at this opportunity, sailing his fleet across the treacherously shallow waters. Realizing what Perry was trying to do, Barclay rounded up his fleet and sailed to the Americans, intent on destroying the tiny Lake Erie Fleet for good. And it seemed that this would be the case, as the American fleet appeared to be trapped on a sandbar. By shear luck, the winds started blowing to the East, and Perry was able to maneuver his ships into the ideal position. The Lawerence was severely damaged, but instead of surrendering the ship, Perry had the remainder of his crew row to the Niagara in heavy gunfire. Once aboard, Perry continued to command the fleet, sending in smaller ship to distract the British. The Niagara broke through the British defensive line, and Perry secured the American’s victory. Barclay surrendered his entire fleet, which had never happened to the British Navy before. Perry took back the barely floating Lawrence and had Barclay officially surrender on the tattered ship so that he could see all of the dead and wounded sailors. Perry famously wrote in his letter to General William Henry Harrison:

“We have met the enemy and they are ours.”

Perry’s Frustrations

(from U.S. National Archives and record Administration)

Unfortunately, Commodore Chauncey had unintentionally failed Perry yet again. There was a great controversy between Perry and his Commanding Officer, Jesse Elliot. Chauncey had been ignoring Perry’s requests before the battle, and if he did respond to Perry’s request for sailors and equipment, he sent inadequate amounts at the lowest quality, including Elliot. Perry and his Junior Officers witnessed Elliot’s failure to accomplish the mission. He held back the Niagara while Perry suffered catastrophic damage on board the Lawrence. The Lawrence may have met a different fate if Elliot had decided to take action and assist Perry in attacking Barclay’s fleet. After Perry had abandoned the Lawrence and boarded the Niagara, Elliot asked the question “How is the day going?”. After Perry had witnessed his beloved ship being destroyed, along with 27 dead sailors and countless others wounded, he was extremely peeved by Elliot’s remark. Elliot ended up disappearing during the rest of the battle, pretending to be sick in bed. Perry filed charges against Elliot, which he repealed. Elliot lost his honor in the process and was never traditionally recognized as a hero in the battle, even though both him and Perry received the Congressional Gold Medal.

Legacy

Along with receiving the Congressional Gold Medal, Perry was also promoted to the rank of Captain. He continued to serve in the War of 1812, but after the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the war, he never saw any combat again. Perry ended up getting into an argument with a fellow officer. They challenged each other to a pistol duel. Perry did not fire, further increasing his honor. After being assigned commander of the John Adams and the Nonesuch. He was to conduct a diplomatic mission to Venezuela, but ended up contracting yellow fever while conducting the mission. Oliver Hazard Perry died on his 34th birthday in 1819. Numerous towns throughout the United States were names after him, and his fame continued to grow, even after Elliot continued to slander his name, but it actually had the reverse effect. Perry achieved a heroic status, and President Monroe said that his death was a “national calamity”. His court marshals were pardoned, and Elliot became more and more despised. Perry became a legend in the War of 1812.

Perry’s actions were selfless and courageous. He never gave up on improving the Lake Erie fleet, even when all he had was a single cannon, a couple of half-built ships, and barely any crew members. He strove for success, and success he achieved. He was a brilliant strategist, and inspired his men to achieve victory. Perry was issued a Congressional Gold Medal for his success at the Battle of Lake Erie (also known as Perry’s Victory). Although the battle was small scale, it provided the Americans with a significant strategic advantage for the Great Lakes area. If not for Perry’s protectiveness and hard work, it would have been unlikely that the British forces would have been defeated at Lake Erie.

Personal Experience

When I was younger, I had the chance to visit the Perry Memorial in Put-In-Bay. It was a big white column up on a hill, with Lake Erie in the background. It was spectacular. I really didn’t understand the warfare behind the event, but I remembered Perry’s name. When the MHUGL project came up, I immediately thought of the Battle of Put-In-Bay, and decided to delve further into the Historical Monument that I had visited as a kid. I would recommend that if given the chance, visit the Perry’s Victory Monument. You have to take a Ferry to get to it, and the green-blue water of Lake Erie is mesmerizing. I would very much like to visit the memorial again with all of the new information that I have learned about the topic.

Primary Sources

1) Hamilton, Paul, Secretary of the Navy. “Paul Hamilton, Letter, to Oliver Hazard Perry, 31 March 1810.” Letter to Oliver Hazard Perry. 31 Mar. 1810. MS. Navy Department, New York.

2) Perry, Oliver Hazard, Commodore. “U.S. Brig Niagara off the Western Sister Head of Lake Erie, Sept. 10th, 1813 4 P.m.” Letter to Paul Hamilton, Secretary of the Navy. 10 Sept. 1813. MS. Washington D.C.

3) Perry, Oliver Hazard, Commodore. DONT GIVE UP THE SHIP. 1813. New York Historical Society, New York.

Secondary Sources

4) Fleming, Thomas. “War of 1812: Battle of Lake Erie: Oliver Perry’s Miraculous Victory.”History Net Where History Comes Alive World US History Online. 12 June. 2006.

5) Altoff, Gerry. “Oliver Hazard Perry and the Battle of Lake Erie.” Michigan Historical Review, 1988.

6) Klein, Christopher. “The Battle of Lake Erie, 200 Years Ago.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, 10 Sept. 2013.

7) Baily, Richard. “Oliver Hazard Perry: The Hero of Lake Erie.” Oliver Hazard Perry: The Hero of Lake Erie. Redwood Library & Athenæum, 3 July 2013.