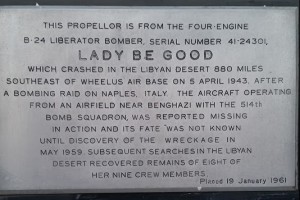

In a little town called Lake Linden in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan there lies a monument that holds the propeller of a WWII aircraft. Tech. Sgt. Robert E. LaMotte and his fellow crew members are a good representation of the risks that were involved in flight during WWII as they were the crew members on the Lady Be Good, the B-24 Liberator to which the propeller belonged. The Lady Be Good and 24 other bombers were tasked with a mission to bomb Naples, Italy at dusk on April 4th, 1943 and return to the operational base in Soluch, Libya under the cover of darkness. Unfortunately, they never made it home.

Leading Up to Their Mission:

By 1942, Axis powers occupied a majority of Europe with the exception of Great Britain and a few other neutral countries. This made it very difficult for the Allied countries to break through German lines and get to Berlin. Another place the Axis had a hold on was Northern Africa. The Allied powers sought to gain access to Europe by overpowering the Axis in Northern Africa. Another advantage that both sides were seeking to gain by controlling Northern Arica was the mass amounts of strategic resources such as oil the area contained. The US landed in Northern Africa in the year of 1943 and restlessly fought for control of the area. Once the US and its allies had a good position in Africa, it could swoop through and take Italy to gain some footholds in Europe. One main Allied campaign in North Africa was the Western Desert campaign. After this campaign the US and its allies, thanks to a lot of help from the British, were able to take over Libya in early 1943. From Libya the US was able to start performing bombing raids on Italy to gain a strategic upper hand. This is where the Lady Be Good and her crew come onto the scene.

The Mission:

The Lady Be Good was assigned to the 514th Bomb Squadron and 376th Bomb Group on March 27, 1943. There were two sections for the mission to bomb Naples, Italy: A section and B section. The Lady Be Good was part of the B section. Section B contained 13 planes divided into two elements, which were then divided again into two flights each. Their objective was to fly high during the day to drop bombs on Naples, Italy and return low at night to their home station in Soluch, Libya. They were not permitted any fighters to protect them from air-to-air attacks and were instructed to defends themselves using their own weapons and flight tactics. B section, took off at roughly 1:50 pm on April 4, 1943. As with many planes that flew in that area during World War II, Section B’s airplanes were starting to have engine trouble after takeoff due to the sandstorms in the area. By about 7:50 pm (roughly 6 hours after the start of the mission), B section only consisted of 4 other planes due to planes returning to base because of oil leaks, gas leaks, and oxygen masks freezing. By this time the darkness was causing problems for the mission, so Lt. Hatton, the new leader of the section, ordered B Section to abort the mission and return to base. The planes operated by Lt. Gluck, Lt. Swarner, and Lt. Worley all eventually safely landed between 10:45 pm and 11:10 pm. Lt. Hatton’s plane (the Lady Be Good), however, had yet to land. By 11:10 pm a radio direction finder reported the Lady Be Good as flying over the Mediterranean Sea on course for Soluch. The last message received by the Lt. Hatton was “My ADF has malfunctioned. Please give me a QDM.” An ADF is an indicator on a compass and a QDM is a magnetic heading to a station. It can be inferred from this that the crew’s navigation was off. Unfortunately, 1st Lt. Hatton flew over the coastline and missed his landing point, most likely caused by the lack of vision in the darkness and broken navigation system. It is speculated that once the Lady Be Good flew over Soluch, their compass kept directing them in a direction of 330 degrees and they just flew right over the landing zone. Since the B24 was running low on fuel the crew eventually decide to eject from the air craft and parachute to ground. The crew crash landed in the Libyan desert without much sense of direction and little to no supplies.

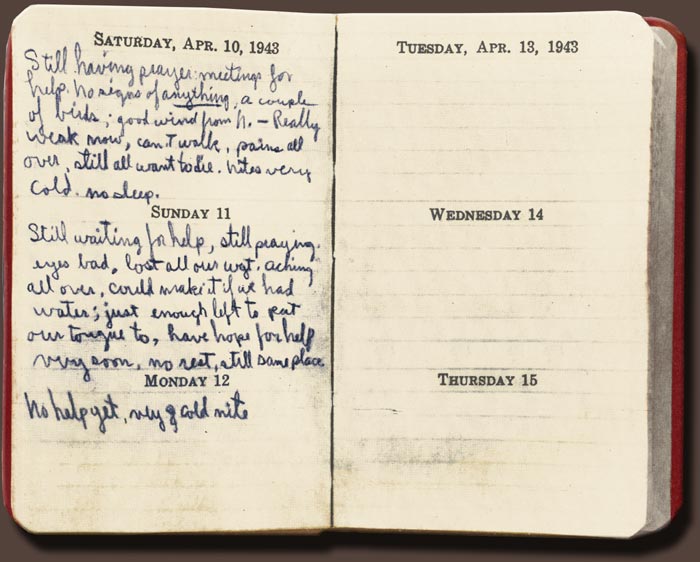

The Lady Be Good crash landed in a plateau known as Calancsio Serir with what is known as the impassible Libyan Sand Sea just 70 miles to their north. 100 miles to their south was a mountain range. They were essentially trapped in a “U” shape of the Libyan Sand with the mountain range filling in the opening of the “U”. It is suspected by experts that it is impossible to escape the plateau and because of this none of the nomads from the region ever visit the area. They estimate that a human can only survive two days if they are found in the situation Robert LaMotte and his fellow crew members found themselves in. This estimate even included extra water, which the crew did not have! Based on the journals kept by Tech. Sgt. Harold J. Ripslinger and Lt. Robert F. Toner, the crew went through 5 phases during their post-bailout expedition. These 5 phases were: initial rendezvous of crew members (besides Lt. John S. Woravka, Bombardier who never met up with the rest), initial hope of being rescued, recognition of their situation, exhaustion, and loss of hope. Pictures of the diaries can be found below. The crew ended up lasting over a week and travelled roughly 50 miles all on their own with limited water, which is remarkable given their circumstances. According to Lt. Toner, they only had a few rations of food and half of a canteen of water. The desert was also very windy and very cold at night, but scorching hot in the day time (roughly 135 degrees). Lieutenants Hatton, Toner, Hays and Sergeants Adams and LaMotte ended their trek on April 9th, too exhausted to continue. Sergeants Shelley, Moore and Ripslinger continued on in search for help, but were unsuccessful. Reading the diaries is quite the tear-jerker, but it gives one a very real feel of what the crew went through during their search for salvation. It can be seen to the right where the remains of each crew member were found as well as where the Lady Be Good crash landed.

Discovery of the Crash Landing:

It wasn’t until 16 years later in 1959 when a British Oil Exploration team was flying over the Libyan Desert and identified the remains of the Lady Be Good that the story was revealed. To much surprise, the poor B-24 Liberator was still in decent shape as one engine, the radio and the 50 caliber machine guns were all still operational. There was also coffee and tea found onboard that was still drinkable. After the plane was discovered, the US sought to find more regarding the crash. They ended up finding the remains of the crew members scattered all throughout the desert. Due to Muamar Gaddafi’s interest in the air craft, a good majority of the it can be found in a storage facility in Tobruk, Libya.

Legacy:

Tech. Sgt. Robert E. LaMotte was the Radio Operator of the Lady Be Good. He was from the city of Lake Linden located in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Robert LaMotte’s legacy lives on in the members of Michigan Technological University’s Arnold Air Society squadron as they have named the squadron after him and go out every year to wash the propeller that honors the brave men who lost their lives in the crash of the Lady Be Good. There are also a few books and movies made about the plane and its crew. The Lady Be Good crew can be found below.

1st Lt. William j. Hatton, Pilot

2nd Lt. Robert f. Toner, Co-Pilot

2nd Lt. D.P. Hays, Navigator

2nd Lt. John S. Woravka, Bombardier

Tech. Sgt. Harold S. Ripslinger, Flight Engineer

Tech. Sgt. Robert E. LaMotte, Radio Operator

Staff Sgt. Guy E. Shelley, Gunner & Assistant Flight Engineer

Staff Sgt. Vernon L. Moore, Gunner & Assistant Radio Operator

Staff Sgt. Samuel E. Adams, Gunner

Primary Sources:

- “The “Lady Be Good” Ghost Bomber of WWII – The Diary Page.” The “Lady Be Good” Ghost Bomber of WWII – The Diary Page.

- Department of Defense. Office of Public Affairs. Concerning Mystery B-24 Found in Libyan Desert. Washington D.C.: Department of Defense, 2016. Retrieved from Houghton County Historical Society.

- “Find Strayed Bomber.” The Science News-Letter6 (1959): 85.

Secondary Sources:

- King, Tim. “Libya: Can We Have the ‘Lady Be Good’ Back Now Please?” Salem-News.com. 13 Dec. 2011.

- Bellows, Alan. “The Remains of Lady Be Good.” Damn Interesting. N.p., 04 Apr. 2006.

- Truthan, Ed. “The Lady Be Good – Ghost Bomber of WWII.” The Lady Be Good – Ghost Bomber of WWII.

- Martinez, Mario. Lady’s Men: The Story of World War II’s Mystery Bomber and Her Crew. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute, 1999.

For Further Information:

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0065007/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lady_Be_Good_(aircraft)

|

|

|