Group of native warriors during the Dakota Wars, 1862.

Video Spotlight: U.S. Dakota War of 1862. Indian Country Today, Indian Country Today Media Network. 2017. Link.

Any relationship built off deception, lies and prejudice is not one built to last or one that can continue peacefully without any sort of conflict. The perfect example of a ‘toxic friendship’ from the beginning is the relationship between the native peoples and the European settlers in the United States; more specifically the tempestuous relationship between the U.S. government and the Sioux nation in Southern and Western Minnesota. One of the most shocking, unjust and discriminatory events in our nation’s history is the story of the Dakota War/Sioux Execution of 1862. Extremely unjust, unfair and discriminatory methods were used to get Sioux chiefs to sign treaties the U.S. government had no intention of fulfilling. Essentially leading the natives to give their land away for free and forced them on to reservations. Eventually these feelings of mistrust and prejudice led the Sioux people to fight back against the white settlers. This post examines the reasons behind the war, the events during the war itself with first had accounts from both soldiers and natives, and the impact of the Dakota Wars on the lives of the native people still living in Minnesota today.

Causes of the War

This story starts much differently than most tales of war because it starts with peace. The Treaty of Traverse des Sioux of 1851 was an agreement made between several tribes of Dakota natives and the United States government that the tribes would be compensated for land in what is now southern and western Minnesota (Weber). Leaders of the Dakota tribes were rushed to sell their land because they feared the United States government would just take it if they did not sell it. Combined, the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux and the Treaty of Mendota, also signed around this time, the Dakota had ceded about 21 million acres for 1.6 million dollars (Minnesota Treaties). The tribes never saw any of the money they sold their land for. In an interview done in the early 1900s a native man named Jerome Big Eagle, who fought in the Dakota War talked about the increasing unhappiness of the tribes following the sale of their land. He talks about how the counsels decided against going to war much earlier that 1862 because of the payment that was coming from the government. They waited and waited, but no one from the government ever came to pay them. They travelled to the agencies to pick up the payment, in gold, themselves, but were told that because of the war gold was scarce and they would not be paid. (Jerome Big Eagle, pg. 387-388). Treaties made with natives during this time hardly ever followed through how they were supposed to; there was never any translators for the natives and all documents were written only in English. Right from the beginning the government had included a separate document within the treaty from a fur trader Joseph R. Brown. This document was known as the Traders’ Paper and it allowed the government to pay off debts to fur traders using the money owed to tribes in the treaty (Weber). The Sioux were not aware of this document when they signed the treaty and were obviously angered when they were told the payment would not be made. This blatant lying and broken promise was one of many the natives dealt with during the United States’ rampage to conquer the west.

Timeline of the War

The unfair signing methods and deception of these treaties culminated into the heart of the Dakota War. It started on the evening of August 17th, 1862, when a hunting party of four Dakota men were returning home, they happened upon a white settler, followed him back to his village and suggested a shooting match. After the shooting match the Dakota men turned their guns on the white settlers, killing five; they returned home where they told their chief and elders who decided it was time to go to war (The Acton Incident). The war, which lasted four months and spread across central Minnesota and into North and South Dakota claimed many lives. Dakota men attacked settlements all around the Minnesota River valley for five weeks from August through September of 1862. These attacks eventually led to 40,000 white settlers fleeing their homes and about 800 white settlers and soldiers dying (Kunnen-Jones). In a book called The Minnesota Massacre written by A.P. Connolly tells about the homes of villagers after an attack from the Sioux, “Homes, beautiful prairie homes of yesterday, to-day have sunken out of sight, buried in their own ashes…” (Connolly, pg. 20). The author goes on to tell about a family whose house was burned to the ground, the wife was killed by a tomahawk and the two sons were chased through a corn field by natives never to be seen again (Connolly, pg. 20). A letter written by someone’s great grandfather who lived near Fort Ridgely during this battle, described the scene of their village after the natives passed through. He talks about the natives burning crops and homes, chopping off people’s feet and ripping their hearts out (Rieke). The killing of innocent people is a sad truth of war. While they were not directly to blame for the way the natives had been treated by the government, they were an agent for the natives, a constant reminder that their way of life was being taken from them and given to the new comers.

Refugees leaving their homes on the first day of the Dakota War, 1862.

Boris & Natasha. “Minnesota’s Other Civil War”. 1862 Dakota War. Link.

The U.S. Army, who was also fighting in the Civil War at the time, were called into action in mid-September and their forces began to overwhelm those of the natives. In the interview with Jerome Big Eagle he talks about hearing of the soldiers being called from Fort Snelling. He and his band rushed to try and meet the other Sioux fighting at the river, but by the time he and his men arrived the fight was over, and many natives and soldiers lay dead on the ground. The fighting was brutal, many of the men seemed to have been shot after they had died (Jerome Big Eagle, pg. 391). The Dakota War was finally gaining the attention of President Lincoln after it spilled into western South Dakota, Northern Nebraska and Northern Iowa. With four states now involved Lincoln decided to create a new Army Department of the Northwest, which was headquartered in Fort Snelling and overseen by Major General John Pope (Boris & Natasha). The tides began to change as federal troops were brought in vast numbers, and Little Crow, chief of the Sioux, was beginning to see they were outnumbered. The conflict ended soon after when Henry Sibley and his men marched on Yellow Medicine and captured 2,000 Sioux peoples (Wiener). After the fighting had ended the issue became what to do with the captives, he sentenced 303 of them to death, who were sent to Mankato to prison, others were sent to internment camps or other prisons (Boris & Natasha).

Lincoln took into account the abuse and discrimination the natives had faced leading up to the war. 1,600 Dakota women, children and elderly were forced to march 180 miles from their internment camps to Pikes Island at Fort Snelling (Boris & Natasha). At Pikes Island hundreds of natives died in the harsh winter from starvation, hypothermia and a measles outbreak (Boris & Natasha). After reviewing the 303 death sentences himself, President Lincoln made a final decision of 38 Dakota warriors who were found guilty of rape or had participated in the massacring of civilians outside of battles. The rest of the 265 Dakota men were sentenced to prison. The 38 Dakota men were hanged in front of a crowd of nearly 4,000 in downtown Mankato (The Trials & Hanging). The remaining free Dakota people were forced onto reservations or were forced to flee to Canada. Many were dispersed and separated from their tribes and families. This whole conflict has led to years of unresolved feelings of mistrust and brokenness from the native Dakota peoples living in Minnesota to this day.

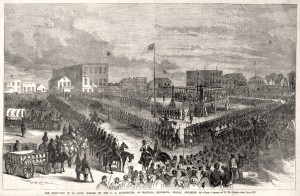

The execution of 38 Dakota men following the Dakota War, December 1862.

The Trials & Hanging. The US-Dakota War of 1862, Minnesota Historical Society. Link.

After the War

This story is difficult to hear at first. It is a sad and deeply shameful part of Minnesota’s past and it is something that has been covered up for a long time, but historians are finally shedding light on this terrible tragedy. The natives were treated extremely unjustly during their “trials” and even before when they believed they were partners in business with the United States government. None of the treaties, documents or sentencing was done in the Sioux people’s native language, they never fully knew what they were being accused of or what they were signing their rights and land away to. It is a fundamental right, laid out in the 6th Amendment in the Constitution of the United States that an individual has the right to know what they are being accused of and have the right to a trial by an impartial jury; but that did not apply to the native people of this land. The idea of Manifest Destiny is a dangerous one. Natives who had lived in the Minnesota River valley for thousands of years were being kicked from their homes. They were doing everything they could to protect their way of life from friends and invaders alike.

In the interview with Jerome Big Eagle he talks about the way the white men treated the natives; they abused them and “they always seemed to say by their manner when they saw an Indian ‘I am much better than you’” (Jerome Big Eagle, pg. 385). He goes on to talk about how much worse abuse the native women took from the white men, he says they disgraced them and there was no excuse for it (Jerome Big Eagle, pg. 385). After reading real accounts of natives who lived during this time, it is no surprise they went to war and they did not care who they killed during that war. Their peace and their lives had already been taken from them, they had tried to befriend the settlers, they had tried to be open and live amongst the new comers in solidarity, but now they had no choice left but to fight everyone and everything that stood against them. The conflict never really ceased. While the fighting in the Minnesota River Valley may have ended, the conflict continued westward with battles such as Little Bighorn and Wounded Knee. And while the ‘war’ today may not include actual bloodshed, natives are still fighting to protect their land and their traditions from the same outsiders who took it from them 200 years ago.

Primary sources:

1. Connolly, A.P. The Minnesota Massacre and the Sioux War of 1862-63. Past Commander U.S. Grant Post, No. 8, G.A.R. Department of Illinois. file:///C:/Users/g_fisher13/Downloads/thrillingnarrati00connuoft.pdf

2. Jerome Big Eagle. Interviewed by a representative of the Pioneer Press. November 1900. 383-391. file:///C:/Users/g_fisher13/Downloads/siouxstoryofwarc00wamdrich.pdf

3. Rieke, George. Letter to brother. Rewritten by D. Busch. The US-Dakota War of 1862. October 5, 1862. http://www.usdakotawar.org/stories/share-your-story/2776

Secondary Sources:

4. Kunnen-Jones, Marianne. “Pioneer Accounts of Sioux Uprising”. University of Cincinnati, University of Cincinnati. 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20080619085622/http:/www.uc.edu/news/sioux.htm

5. Minnesota Treaties. The US-Dakota War of 1862, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.usdakotawar.org/history/treaties/minnesota-treaties

6. The Acton Incident. The US-Dakota War of 1862, Minnesota Historical Society. http://usdakotawar.org/history/acton-incident

7. The Trials & Hanging. The US-Dakota War of 1862, Minnesota Historical Society. http://usdakotawar.org/history/aftermath/trials-hanging

8. Weber, Eric. “Treaty of Traverse des Sioux, 1851.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/event/treaty-traverse-des-sioux-1851

9. Wiener, John. “Largest Mass Execution in US History: 150 Years Ago Today”. American Public University, American Public University. December 26, 2012. https://www.thenation.com/article/largest-mass-execution-us-history-150-years-ago-today/

Further Reading:

10. Boris & Natasha. “Minnesota’s Other Civil War”. 1862 Dakota War. http://exploringoffthebeatenpath.com/Battlefields/DakotaWar/index.html

Featured Image:

11. Schwabe, Henry August. “The Siege of New Ulm“. 1902. http://exploringoffthebeatenpath.com/Battlefields/DakotaWar/BattleofNewUlm.jpg