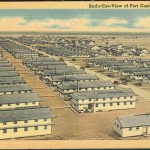

Fort Custer was a military installation that was built in 1917 between Battle Creek and Kalamazoo in Augusta, Michigan. It was created as a training installation for troops during WWI and WWII and is comprised of a few major sections. These include the barracks, state park, and industrial park. The barracks section of the installation, seen in passing from a car, takes up a large amount of space. It contains a large number of housing buildings laid out in neat even lines surrounded by open training fields and other buildings. This area is used as a training space and housing for the Michigan National Guard. It was also used as a POW camp for German soldiers during WWII as well as a medical facility for casualties during WWII.

The Fort Custer National Cemetery is placed near the grounds of the current training base, and it is the resting place of 26 German POWs who died while at the Fort. Of these, 16 of them died when the truck that they were being transported in was hit by a train on its way to a sugar beet farm. There is a memorial on the grounds commemorating them and a number of German veterans visit to pay their respects.

The industrial park, which now houses a score of factories which are owned by numerous companies, was once a massive training ground for the troops needed during WWI and WWII. While this area was operated by the Army, it oversaw the training of 300,000 troops during WWII alone. This area also saw use as labor areas for the German POWs interred at Fort Custer during the war. This part of the grounds was run from the forts creation to the 1960s when it was shut down and abandoned. The land was then given to Battle Creek Unlimited who turned it into the industrial park it is today.

All of this area encompasses that which is known as Fort Custer. The actual military installation is now much smaller than it was in the past, yet it is just as important to the surrounding cities and towns that it provides it services to.

POWs in Michigan

German POWs numbered fairly high in the United States and a number of them assisted in labor in the Midwestern states. By the time 1943 rolled around prisoners of war from Germany had started to flow into camps that had recently been converted or constructed in Michigan. Many German prisoners were transferred from camps in Great Britain to camps in the United States. A large number of prisoners were transferred up from Texas and other southern states to camps in Michigan. These prisoners were held at Camp Custer until they were moved to any of the other camps in and around Michigan.

The number of German soldiers captured and then held in the United States during the war outnumbered the number of Americans held as POWs in Germany by a factor of 4 to 1. These men were integral to the industry of Michigan and other Midwestern states, as these prisoners were used as an influx to the labor force on the farms of these states.

The work that these men performed was not forced upon them and was done so that they could have something to do during their lengthy incarceration. As America followed the Geneva Convention for the holding of prisoners of war, these camps were well supplied with food and other amenities. However, in order for the prisoners to get access to extra amenities from the camps store, the prisoners would need to work for them. On a farm near Eau Claire, Michigan, these working men were paid 80 cents for each work day performed. While this may not seem like a lot of money, it comes out to around 11 U.S. dollars after inflation is induced.

One of these farms was owned by William Teichmann in Eau Claire. Mr. Teichmann hired the German workers from the U.S. military to assist him and his family in harvesting his 120 acre farm. Many farms in the Midwest needed all the extra labor help that they could get, as these farms used seasonal labor from the lower parts of the U.S. With the need for troops and the rationing on rubber and gas, these men did not come up from the south to help work the farm. Farmers like the Teichmann family pleaded to the U.S. government that they needed a labor force or they wouldn’t be able to harvest effectively. The call was answered by between 5,000 to 8,000 German prisoners all throughout Michigan. This veritable army of a labor force worked in Michigan’s factories, orchards, and lumber mills.

The prisoners that helped Mr. Teichmann at his farm made sure to keep in touch with him and his family using mailed letters after they were released from the POW camp following Germany’s defeat. This was started by Mr. Teichmann when he told each and every German POW that worked with him to make sure to write when they returned home and that if they ever need help to just ask for it and he would be there. This hospitality, generosity, this humanity, lead to the Teichmann family getting around 50 letters from prisoners that they employed for the three seasons of work that he needed. These letters helped document troubles that post war Germany and her citizens faced. Similar stories were all over the Midwest, as the moral of these prisoners was quite high due to the condition of the camps they were held in and because they had previously been held in camps in the southern states or they were being held at British camps, which were a bit less hospitable.

Mr. Teichmann’s farm was a bit of an oddity compared to some of the other farms in the area, as the Teichmann family had moved from Germany in 1890. Mr. Teichmann often found that he had an easier time conversing with and ordering around the German prisoners. Because of this he would often assist the other farms in the area as an interpreter between the workers and farm owners. Mr. Teichmann was considered a full-blooded German in the eyes of the prisoner workers where he was. One soldier, Gerhard, told him that “When I was on your farm it felt like being at home”. This camaraderie showed itself in the letters that the family got after the war; often starting with a phrase containing the words “homeland” or “old country”.

The Teichmann family did not interact too much with the German workers due to the amount of work that needed to be done. However, one of these times of respite and conversation was during their transfer period from the camp to the farm. During one of these times, Mr. Teichmann accidentally ran over a small chicken from one of the other local farms. This moment was captured by one of the soldiers in the truck with him via a hand drawn sketch.

Stories from Prisoners

Elmer B. was a German corporal who served in the Wehrmacht starting in 1937. He thought of himself as a proud German and was part of the Nationalist party. During the war, Elmer took part in the invasion of Poland, France, and the Soviet Union. In 1942, Elmer joined up with the Afrika Korps and was involved in the fighting in Tunisia and Libya. When he was captured, Elmer spent four whole months in the sweltering heat of a British POW camp in Algiers. Elmer was transferred to Norfolk, Virginia where he would take a train to Camp Custer where he spent the rest of the war. During his time at Camp Custer, Elmer used his skills gained as a butcher in Germany to work as a cook supervisor for the camp. Elmer did not know any English when he was captured and thus he decided to take part in an English class during his incarceration at Camp Custer. When interviewed by Barbara Heisler, Elmer stated that he was satisfied by the living conditions in the camp and the only times that he had complaints was during the food rationing in 1945 and when he was put into solitary confinement for stealing and destroying some anti-Nazi newspapers (Der Ruf) that he considered to be anti-German in content. Also during his interview, Elmer told Barbara that his views of the United States from in the camp were quite positive and he expressed his interest in visiting the U.S. later with his wife.

A large number of Germans returned to Germany and their families after the war ended. However, some of them like Karl H. found their way back to the country where they had once been held. Karl fought for Germany form 1940 when he was drafted till 1944 when he was captured in Italy. Karl H. was transferred via the same route as Elmer and found himself being held in Fort Custer. While Karl was being held at Fort Custer, he met a woman named Stella, who was a civilian worker with the purchasing and contracting department. They became quick friends and kept in contact even after Karl transferred to England. The two were reunited in 1948 when Stella found a job with the American Occupation Forces and the two married a year later. Karl and Stella moved back to America and Karl ended up working in Ypsilanti, Michigan for 33 more years.

The Security of a Fort

Due to the conditions that the prisoners of war were being held in were more than hospitable and the weather comfortable, the security detail with working prisoners was rather relaxed. More often than not, one could see a group of up to 100 prisoners being guarded by only one guard. It wasn’t uncommon to see the guard assigned to the group of prisoners to be sleeping on the job, leaving the group to watch themselves. One prisoner, Hienz, had a job with a guard watching over the camp stove. During these shifts, Hienz would read an English dictionary and talk to the guard he was with; waking him if he slept to long so Hienz could learn more English. By 1944, Hienz was performing work without a guard as he assisted in additions to Fort Custer. Another prisoner, Rudolf H., stated that “guarding by the Americans became very superficial.”

The camps were barricaded with barbed wire fences and guarded by watchtowers, but it was very rare to see a POW try and escape from the camp and if it did happen, the escapees would be recaptured not long after. Why would the prisoners want to escape and where would they go. These men were thousands of miles from Europe and even then, their accent wouldn’t get them anywhere in the US. As one prisoner from Fort Custer stated, “it would be foolish to escape from a place where we were enjoying relative freedom and good care to return to a Germany where death, hunger and other dangers were still the rule of the day.” Each camp had an elected intermediate that would speak with the heads of the camp when they had any concerns. Other than that, the structure of prisoners often reflected that of American POWs in camps, keeping their ranks even when they were being held prisoner.

Primary Sources

- Hahn, L. (2000) Germans in the Orchards: Post-World War II Letters from Ex-POW Agricultural Workers to a Midwestern Farmer

- Heisler, B. S. (2013) From German Prisoner of War to American Citizen

Secondary/Tertiary Sources

- Buntjer, J. (2010) Tending to the boys of war

- Hall, K. T. (2015) The Befriended Enemy: German Prisoners of War in Michigan

- Butler, M. G. (2009) Camp Custer

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (2015) Fort Custer National Cemetery

- Krammer, A. P. (1976) German Prisoners of War in the United States

- The Yale expositor (1917) Health at Custer Nearly Perfect

Further Reading

- Fort Custer Historical Society Museum in the Fort.